After 50 years, NPR upholds public broadcasting’s founding values

April Simpson / Current

In 1905, 10 years before the invention of educational radio in the state of Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin President Charles Van Hise provided a core idea when he said, “I shall never be content until the beneficent influence of the University reaches every family of the state.” This became popularized as the Wisconsin Idea, that “the boundaries of the campus are the boundaries of the state.”

Today we carry access to the world’s information in the palms of our hands, but early-1900s Wisconsin was a different story. Newspapers were common, but the literacy rate was 61%. The founders of WPR’s first station, 9XM, saw how the new wireless technology could provide life-changing information to the mostly rural state. They used the power of radio to broadcast what would help the most Wisconsinites at the time — the weather and crop prices in 1918. It wasn’t until Monday, Jan. 3, 1921 that regular programming was launched.

More than half a century later, The Wisconsin Idea would still resonate. As a member of the founding board of directors of NPR, I, Bill Siemering, was tasked to write the Purposes and Mission. Wanting to differentiate the new public radio from PBS and from educational and commercial radio and to make the case for radio as an imaginative, powerful medium, I wrote:

The total service should be trustworthy, enhance intellectual development, expand knowledge, deepen aural esthetic enjoyment, increase the pleasure of living in a pluralistic society and result in a service to listeners which makes them more responsive, informed human beings and intelligent responsible citizens of their communities and the world.

As NPR’s Articles of Incorporation approach their 50th anniversary Wednesday, it’s worth asking: How has NPR carved out a spot on our nation’s airwaves, and why is noncommercial media important? NPR’s historical and contemporary practices are reflected in its founding mission statement as it strives to produce content that supports diversity, fairness and democratic information.

From its origins in state universities, classroom curricula were first supported by physics and engineering departments at Midwestern state universities, with experimental physicists more interested in measuring transmission of sound waves than what the content of those sound waves actually conveyed to potential audiences. But the foundational concept that educational technology could be utilized to increase equal access to education inspired rapid educational radio growth through the 1930s through the National Association of Educational Broadcasters.

In 1934 the Senate passed its first national media policy — the Communications Act. Amid frequency scarcity and an abundance of applications, the Act stipulated that the infrastructure built by commercial broadcasters, which did not require state support to maintain facilities, would receive the majority of AM allocations. The consequence was that close to 85% of educational stations suddenly lost their licenses in 1935 due to their experimental nature.

In the post-Act environment, initially marked by a decimated, scattered educational landscape, Wisconsin Idea–influenced broadcasters transformed into something like a social movement. Hundreds of institutions became galvanized that the Midwestern state universities were right. Radio could serve public education, – and the technology was fated to do more than entertain, promote and profit.

Even commercial broadcasters were on board. The FCC and Office of Education organized a Federal Radio Education Committee in concert with NBC and CBS, which greenlit a research project to determine how well educational broadcasts actually educated audiences. The FREC study, which became known as the Princeton Radio Research Project, helped to innovate modern audience research.

University broadcasters obtained Rockefeller Foundation fellowships to train in station maintenance, audio curricular design and connecting with audiences, setting the precedent for philanthropic underwriting of public media. The president of the University of Wyoming, A.G. Crane, built the first noncommercial media network to reach educational sites, which he presciently coined “public broadcasting.”

When the U.S. entered WWII, researchers at the University of Illinois, Iowa State and Indiana University enlisted with the Office of War Information and military training divisions and applied new audience research techniques, in the process streamlining the clarity and comprehension of instructional broadcasting. By the end of the war, Congress was persuaded to allocate protected frequencies on the new FM dial for educational broadcasting.

With television looming, educational broadcasting in the late 1940s began to look something like today’s public media. Universities began to pour funding into educational broadcasting, and between 1950 and 1953 two major events would change the trajectory of noncommercial media. First, the creation of academic communications departments. The earliest formed in 1947 as the University of Illinois Institute for Communication Research. It pulled from the Princeton Radio Research Project and became a designated departmental home for educational broadcasting. From Illinois and WNYC, educators built the prototype for public media. Called the “bicycle network,” shows were peddled from university station to university station around the country thanks to a Kellogg grant.

Second, in 1952 the FCC allocated 11.7% of television frequencies for educational use. Armed with TV channels and having realized a vision of nonprofit media distribution, the Ford Foundation became persuaded to fund NAEB radio and television programs. Between roughly 1953 and 1967, universities applied production techniques of the BBC and network broadcasters to their craft. And through the mid-1950s the genres we associate with public media started to reach aesthetic maturation: news reports, travel shows, cooking shows, public affairs and educational children’s programming.

By 1967, educational radio’s fortunes had turned around. The Public Broadcasting Act mandated NPR, PBS and CPB. Originally titled the “Public Television Act,” radio was added only at the last instance. With support from the Carnegie Commission and multiple senators, Congress invited the NAEB to migrate producers, showrunners, and engineers from state universities to Washington, D.C., Boston, and New York to populate a “fourth network.” NPR was the final culmination of the Wisconsin Idea, the bicycle tape exchange network and the pioneering work of university researchers, but as a federal extension service NPR faced new responsibilities and challenges.

After Don Quayle was hired as the first NPR president, I, Bill Siemering, was hired as the director of programming to make these words a reality. In describing what became All Things Considered, I wrote:

The program would be well paced, flexible, and a service primarily for a general audience. It would not, however, substitute superficial blandness for genuine diversity of regions, values, and cultural and ethnic minorities which comprise American society; it would speak with many voices and many dialects. The editorial attitude would be that of inquiry, curiosity, concern for the quality of life, critical, problem-solving, and life loving. The listener should come to rely upon it as a source of information of consequence; that having listened has made a difference in his attitude toward his environment and himself.

The beginning was rocky. NPR could have a brilliant piece and a poor one in the same program. It didn’t get as many pieces from stations as anticipated. It was developing the “NPR sound.” The first Public Radio Conference was about two weeks after NPR went live, and Bill felt hostility. Some managers were expecting NPR to sound like the big guys at CBS. They asked, “Who are these people?”

All Things Considered tried a number of hosts; it wasn’t until March 1972 that Susan Stamberg started hosting with Mike Waters, becoming the first woman to host a national news program. It was a painful period; however, ATC had enough good work to keep going. Later that year, an ATC episode broadcast in October 1972 received the network’s first Peabody award.

The real turning point in NPR’s growth came when it launched the news and information program Morning Edition Nov. 5, 1979. Made possible by a 50% increase in NPR’s budget during the first 18 months of the presidency of Frank Mankiewicz, the show tapped into morning drive, when most people listen to radio. The emphasis shifted toward news and information, rather than the deeper analysis on ATC. After a year, about 90% of stations were carrying ME and increased their audience.

While educational radio was heavily influenced by the instructional needs of the university, NPR’s Mission Statement and first shows emphasized the plights of local communities and ordinary people, helping to found a unique vision for journalism. As Jack Mitchell has noted, traditional journalism assigned an authoritative role to the journalist. Public affairs programs have conventionally featured experts, office holders, candidates and spokespersons. Siemering’s vision included “people whose credentials came from their own experience.” And this set a strong precedent for the way that NPR has conducted interviews and covers cultural and political events.

The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 had included a Declaration of Policy that noncommercial radio and television programming must be responsive to “the interests of people both in particular localities and throughout the United States to constitute an expression of diversity and excellence.” In contrast to for-profit media, NPR was expressly charged with providing the service of programming for diverse audiences, including programs about “special concerns of these groups.”

Results have been mixed. In the early 1980s, NPR produced weekly documentaries on issues in diversity as the show Horizons. But the network continues to work to diversify its own staff, with Latinos in particular facing low representation in NPR’s ranks.

Yet there are promising developments. Radio Bilingüe set a foundational precedent in 1977 for Spanish-language programming. NPR launched Code Switch, its unit covering issues of race and ethnicity, in 2013, and in 2016 it began distributing the Spanish-language podcast Radio Ambulante.

While PBS acquires and distributes programs from its member stations, NPR was organized to develop, prepare, produce, distribute, license and otherwise make available radio programs for affiliates, putting it at the center of the public radio community. A grassroots network of advocacy, topical and affiliated production groups has grown up around the networks, including Latino Public Broadcasting, Native Public Media, Black Public Media and the Association of Independents in Radio. American Public Media continues to produce important programs for the public radio network, such as Marketplace, while affiliates help to realize a vision for equal representation in noncommercial media.

As NPR enters its second 50 years, it will continue to innovate while facing institutional challenges. In 1971, there were 88 member stations and a total staff of 65; now NPR’s total staff is 862, with 390 in news and 17 overseas bureaus, and the network has 1,008 member and affiliated stations. The total weekly audience for NPR stations is 37 million; 27 million for NPR programs. Ninety-nine million consume NPR content from some platform in a month. NPR is the leading publisher of podcasts and reaches 23.7 million listeners monthly with its offerings.

As audiences have turned to non-appointment listening, NPR has increased its online presence, in the process making radio and digital public media synonymous entry points. NPR’s podcasting division is building new revenue lines and providing audiences with a broader range of content while attracting millions of listeners.

The Trump administration’s 2021 budget has proposed cutting funding for public media for the third consecutive year. Noncommercial media requires public support to continue its work. From the original vision of the Wisconsin Idea, through decades of classroom extension services by radio, to NPR’s Mission Statement, journalism and public affairs programming, the service remains our sound extension of public discourse.

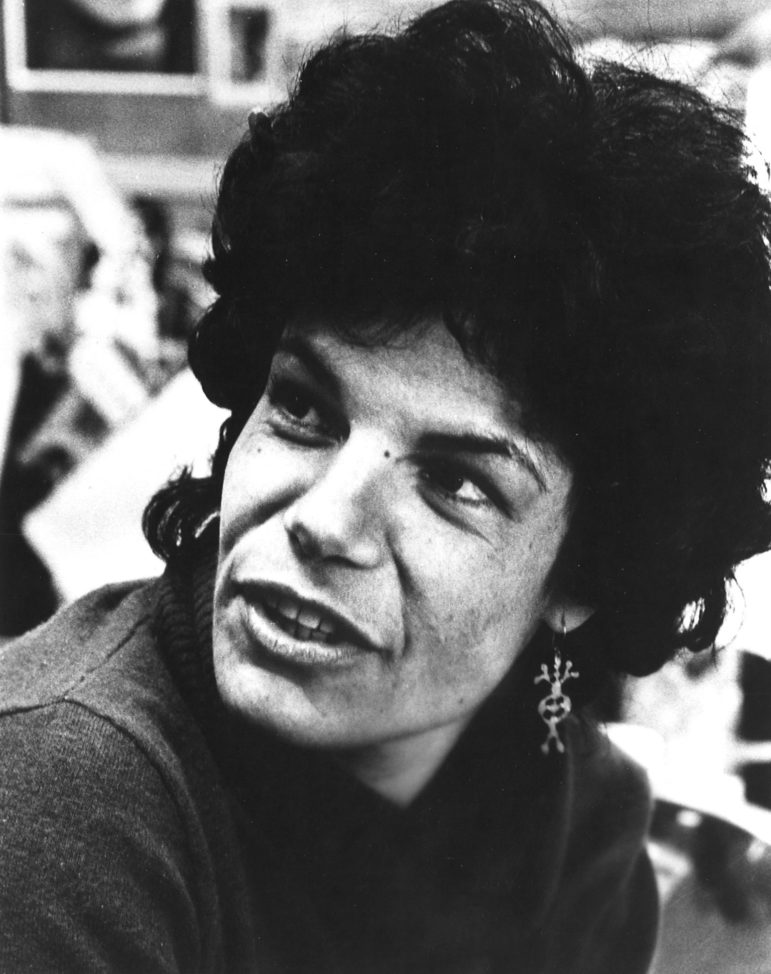

Bill Siemering is a member of the founding board of NPR and author of its original mission statement. Josh Shepperd is assistant professor at The Catholic University of America and the director at the Library of Congress Radio Preservation Task Force.

I still Love PBS but the NEWS division has slowly, until recently, made a severe right hand turn.

I think to be more like what is capable news and the other networks present today. It is no longer

the home of the loyal opposition.They spend as much time throwing soft balls at the right wing talking heads and grill anyone else ruthlessly. Makes you sound just like ABC or Fox. DIsappointed.

I have been a follower of both PBS and NPR. It is my considered opinion that both have been hijacked by fellow travelers of the leftist and socialist media. Public funds, much from Federal Government Operations are now regularly and consistently used to bombard their listeners with decidedly Leftist and Socialist ideas and propaganda which was never intended at their founding as designed by the original granted funds. Both, IMHO, need to be more closely watched to give a more even hand in their programming and reporting.

LMAO at the juxtaposition of the first 2 comments. What an utterly appropriate tribute to the even-handedness of NPR news. Any reputable news outlet should regularly annoy the entire spectrum of political supporters–and maybe compel NPR listeners everywhere to weaponize their mugs and tote bags;)

Thank You! I love your programming. Please stay true to high integrity in journalism. We need all of you. I’m a loyal and regular donor.

Loyal, enthusiastic listener for nearly all 50 years! You have made me a more open, informed and engaged person and have given me a deep, well-rounded education about our culture, our society and the wider world we live in. Now that I am 50 years older, too, NPR broadcasts and podcasts keep me company in this more solitary chapter of life. Ever since my undergrad years, I feel like I have been surrounded by really interesting friends. Thank you!

This is a really amazing history. Thank you.

A fine article, but it must be pointed out that many consider the precursor of public radio to be WCAL in Northfield, Minnesota At 770 on the AM dial this station broadcasting from the campus of St. Olaf College was officially licensed by the U.S. government on May 6, 1922. It broadcast primarily educational programming and Lutheran worship services. A fire destroyed the studio in 1924 and a campaign launched by the class of 1924 and The Northfield News enabled it to continue broadcasting. In doing so, WCAL became the first listenter-supported radio in the country. Eventually a second, and then sole FM frequency at 89.3 was added. WCAL was sold by the college in 2004 to Minnesota Public Radio. But that “betrayal” is another story. I am a proud alumnus of the school (class of 1976), and deeply cherish the role the station played in the history of public radio.

I agree that NPR has become ubiquitous. It is supported by advertising instead of publicly . Independent services like Pacifica and KJAZZ which used to be heard are drowned out by the plethora of NPR affiliates all plying virtually the same content. I think that coverage on NPR is now more diverse than it ever was. That is good.. If we only have two choices at least NPR tries to be representative. We get far right ranting, and sensationalism on one side and NPR very little else. People get more polarized using their media devices getting only the view points that the content providers target at them based on preferences.