CBC approach to election coverage offers lessons for U.S. pubmedia

Canada’s longest federal election since 1872 is underway — 11 weeks, or 78 days, until voting day Oct. 19. Pundits on Canada’s airwaves are already complaining that the race is repetitive. Visit the States, I say to my radio.

Canada’s longest federal election since 1872 is underway — 11 weeks, or 78 days, until voting day Oct. 19. Pundits on Canada’s airwaves are already complaining that the race is repetitive. Visit the States, I say to my radio.

Actually, people in U.S. public media could learn some lessons from visiting Canada — or at least browsing the country’s digital coverage, where some of the most interesting work is being done by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.

The CBC digital team’s latest major voter-engagement initiative is a collaboration with Google’s civic engagement team. Pledge to Vote is a web app that allows Canadians to declare their intention to cast a ballot and to name the top issue that will motivate their choice. The list includes options like the economy, energy and the environment. All responses appear on a map.

Voters can add a tweet-length explanation of their choice and can share their pledges on social media and challenge others to join them.

The idea is to extend the civic engagement and pride that voters express on social media, said Brodie Fenlon, digital managing editor of CBC News, such as pictures taken at the polling booth and “I Voted” stickers.

Aaron Brindle, Google Canada’s spokesperson and a former senior producer at the CBC, cited the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge as an inspiration.

“I don’t expect that challenging people to participate in their democracy is quite the same as filming people getting cold buckets of water poured over their heads,” Brindle said. But he hopes that Pledge to Vote “might, in a non-cynical way, get people engaged,” he said.

Fenlon and other members of his team appeared on CBC radio and television to let the broadcast audience know about the initiative. Within days, the site had tens of thousands of posts, and more than 98,000 in the first week.

Google piloted the “Pledge” platform with a New Year’s resolution tool in 2012 and floated its first election version in India in 2014. The tool was simpler, according to Brindle, and Google launched it without a media partner.

In Canada, the CBC was a natural choice. The network dominates election news and distributes incoming data to other media outlets on election night. But its digital coverage represents a more fundamental commitment to owning election coverage, said Marissa Nelson, the CBC’s senior director of digital media.

“Elections at the CBC are a huge source of pride,” she said. “We want to do it better than everybody, because it’s part of public service and public journalism.”

Fenlon added that the CBC does have to walk a fine line with Pledge to Vote. As Canada’s publicly funded newscaster, it gets particular scrutiny, especially in an election cycle in which support for public broadcasting is itself a campaign issue.

For example, a lot of time went into choosing colors attached to policy areas to make sure they would not overlap with the colors of parties that focus on the issues, Fenlon said. “It’s a strange color palette,” he admitted of the result.

Another concern was that advocates for a certain cause or party would mobilize on the platform in disproportionate numbers. That hasn’t happened so far.

“Ideally,” Fenlon said of the map, “it takes on a life of its own” as a tool provided by the CBC to Canadians who care about the election.

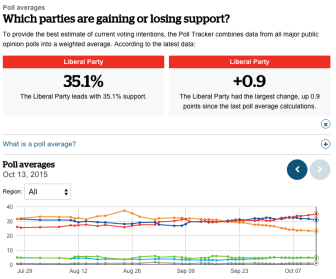

As a less sensationalist, noncommercial broadcaster, the CBC is trying to avoid covering the horse race, Nelson said. But one of its most popular online features has been an election poll tracker. (It’s “going bananas,” said Nelson, with rueful pride.)

As a less sensationalist, noncommercial broadcaster, the CBC is trying to avoid covering the horse race, Nelson said. But one of its most popular online features has been an election poll tracker. (It’s “going bananas,” said Nelson, with rueful pride.)

This is the second election in which the CBC has deployed Vote Compass, an app that allows voters to compare their issue positions to those of the candidates. The CBC’s web team is also extracting sound bites from candidates’ debates and speeches and immediately sharing the video to social media. A simple calendar allows voters to add campaign events, such as debates, to their own personal calendars.

The CBC has also had the opportunity to pilot its election night interface, Nelson said, which combines a display of local results with broadcast coverage.

“Whenever we have provincial elections, we send people from network out to help local coverage,” she said. By the biggest date on the electoral calendar, when the CBC gets its highest web traffic, it’s had time to work out kinks in its tech platforms.

Google has not yet tried to introduce a Pledge to Vote tool in the U.S. I asked U.S. public media stations, including some on the border that broadcast into Canada, whether they were paying attention to the CBC’s digital work. I got the emailed equivalent of blank stares. To be fair, it’s hard to apply lessons learned from an 11-week campaign to an American campaign that lasts two years.

The CBC is more centralized than American public media and is much more dominant in its media market. But the public mission is not that different. The Pledge to Vote tool is scalable to the size of the U.S. electorate, Brindle said. It’s probably most reminiscent of WNYC’s experiment with calling listeners and encouraging them to turn out to vote. And piloting tech tools on an off-year state election night sounds plausible in the American context, though the web platforms used by stations and networks vary widely.

Maybe one lesson lies there. American public media’s raucous network of NPR member stations will never have the unity of the CBC. It’s part of the U.S. system’s charm. But in the long term, enabling behind-the-scenes collaboration on election coverage could benefit local affiliates and NPR.

The loftier goal for election coverage applies everywhere, Nelson said. “Every journalist covers elections because they want people to make better choices,” she said. “Focus on what individual people are interested in and do deep journalism around that.”

Emma Jacobs is a freelance journalist and former NPR member-station reporter currently based in Montreal.

Related stories from Current:

Commercial broadcasters and the cable news channels can also benefit.