Sesame Workshop–HBO deal sparks soul-searching among public broadcasters

Photo: Richard Termine

New episodes featuring Bert, Ernie and other Sesame Street residents will debut this fall on HBO, which bought exclusive first-run distribution rights under a new contact with Sesame Workshop. (Photo: Richard Termine)

The deal to keep Sesame Street going with HBO’s backing may have aided Sesame Workshop’s bottom line, but the long-term cost to the PBS Kids brand and the case for supporting children’s programming on public TV is still to be seen.

The five-year deal, announced Aug. 13, provides free broadcast rights to PBS and its member stations for Sesame Street, as well as two more educational programs. HBO will premiere new episodes of the show, which will then be made available to PBS after nine months.

Cable distribution deals have been key to Sesame Workshop’s financing since the late 1990s. But this is the first contract awarding exclusive access to new Sesame Street episodes to a pay cable channel. The 35 new shows that will debut on HBO this fall will air on PBS stations starting next summer.

The announcement of the deal prompted soul-searching among public broadcasters and others who recalled Sesame Street’s groundbreaking role in using free over-the-air broadcasts to teach preschoolers from low-income families the basic skills they need to succeed in school.

The series, which debuted in 1969 on PBS forerunner National Educational Television, clearly expressed public TV’s mission to reach underserved audiences with educational programming. It became intertwined with the PBS brand and has remained a key element of the case for government support of public broadcasting.

“It seems to me there is something depressing about all this,” PBS Ombudsman Michael Getler lamented in an Aug. 19 column, “an inability in the current environment to keep programs such as this as an honored product of public broadcasting at its best, rather than to have it now associated with pay walls and one more two-tiered system of public separation.”

Officials from PBS declined to discuss the deal publicly. In a statement, PBS said that the HBO contract “does not change the fundamental role PBS and stations play in the lives of families. Sesame Street will continue to air on PBS stations as part of the PBS Kids service, building on a 45-year history.”

Statements from leaders of CPB and the Association of Public Television Stations noted the other educational children’s shows presented exclusively on PBS Kids. “Sesame Street is part of a robust and dynamic array of children’s programming,” said CPB President Pat Harrison.

“Early childhood education has always been an especially important part of our mission,” said APTS’s Pat Butler, adding that those shows will continue to be “available to every child, everywhere, every day, for free.”

A hard truth for public broadcasters is that PBS has paid only a portion of the cost of producing Sesame Street, giving it little say in the Workshop’s new partnership. PBS contributes 10 percent of annual production costs, according to Workshop President Jeffrey Dunn. Representatives of PBS and the Workshop declined to specify PBS’s financial support for the show.

“In effect, Sesame Workshop is tapping into HBO to create more and better content than it can with a PBS-level budget,” said Deron Triff, a former PBS digital strategist who now directs global distribution and licensing for TED. Triff represented PBS during negotiations for the 2004 deal that launched the PBS Kids Sprout channel, a $75 million partnership among the Workshop, PBS, Comcast and HIT Entertainment.

Dunn, a former chief executive at HIT who signed on as the Workshop’s chief executive 10 months ago, describes the HBO contract as a life raft. “We’ve saved Sesame Street for PBS,” he said in an interview.

Shorter show reflects changes

The contract does not affect the PBS Kids fall schedule. While the latest batch of new shows is in its nine-month HBO window, the Workshop will provide PBS with curated Sesame Street episodes compiled from recent shows. The biggest change that viewers will notice — adoption of a switch to a new 30-minute format that PBS introduced last fall — ends broadcasts of the original hour-long format.

Two children’s media researchers noted that the change reflects how children are using media.

“If you look at kids’ viewing habits, they’re much less likely to spend a full hour with one program,” said David Kleeman, an executive with Dubit Ltd., a company that develops digital products for children’s brands and a member of the PBS Kids Next Generation Advisory Board. “They’re more likely to sample multiple things and have many more opportunities to do that.”

Kleeman said he trusts researchers at Sesame Workshop “to know that the half-hour program is structurally sound and gets across the concepts that kids need.”

Dorothy Singer, retired head of Yale University’s Family TV Research and Consultation Center, noted that the educational value of a kid’s TV show isn’t determined by its running time. “Research shows that children can learn very well in a half-hour,” Singer said, as long as fundamentals are stressed, such as repetition of vocabulary and explanation of ideas.

Besides, she noted, “Fred Rogers’ show was 30 minutes for more than 30 years.”

Resources necessary to achieve mission

Currently, the Workshop provides PBS with 44 Sesame episodes per season, 18 of which are new. With HBO paying, the Workshop’s creative team will go into high gear, producing 35 new episodes. The Workshop retains creative and editorial control over Sesame Street.

Production contracts and distribution deals with commercial networks and cable channels have been a key source of the Workshop’s revenue for decades, noted Gary Knell, c.e.o. from 2000–11 and now president of National Geographic. “Everyone there felt all along that we needed to be producing for PBS as well as other outlets that wanted quality children’s content,” he said. Pinky Dinky Doo, an animated early-literacy series, aired on Nick Jr.; the science-based Cro ran on ABC.

And the Workshop has previously produced for HBO: Encyclopedia, with music and skits about alphabet letters, premiered in 1988.

Knell, who played a key role in securing the Workshop’s 1998 cable deal with Nickelodeon, sees the HBO contract as a smart path forward. “Sesame Workshop is about mission,” he said. “But it needs resources and distribution outlets to accomplish the mission.”

The Workshop’s revenues had been declining for three years when Dunn arrived as c.e.o. last October. “I realized early on we had real economic issues,” he said.

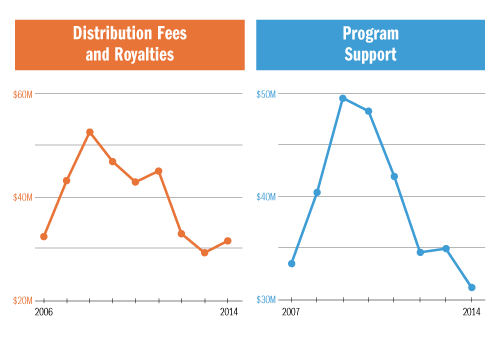

Sesame Workshop divides annual revenue from domestic and international subsidiaries into three main categories: program support, licensing, and distribution fees and royalties. Licensing includes all merchandise that uses the nonprofit company’s intellectual properties, while program support includes individual contributions and government grants. Revenue from DVD sales is categorized as distribution fees and royalties. “Revenue by Source” chart depicts fiscal year 2014 figures. (Analysis by Ben Mook. Graphs: Kelly Martin Design)

In 2008, international licensing revenue, which includes distribution fees, royalties and DVD sales, brought in a hefty $52.7 million; that figure has dropped by nearly 50 percent as of fiscal 2014.

And with the advent of video-on-demand, the domestic DVD market that had been a big moneymaker for the Workshop “sort of imploded,” Dunn said. The Workshop’s domestic DVD sales plunged more than 70 percent from 2008 to 2014.

Licensing revenues had provided 90 percent of Sesame Street’s production costs, and the nonprofit had to turn elsewhere for funding, Dunn said.

Though the deal marks a turning point in the Workshop’s long relationship with PBS, it “brings financial stability to Sesame Street,” said Jack Galmiche, president of Nine Network in St. Louis. And because the program will be provided free to PBS and its member stations, “that enables us to direct the resources that were going into Sesame Street license fees to other new kids’ properties.”

Though the deal marks a turning point in the Workshop’s long relationship with PBS, it “brings financial stability to Sesame Street,” said Jack Galmiche, president of Nine Network in St. Louis. And because the program will be provided free to PBS and its member stations, “that enables us to direct the resources that were going into Sesame Street license fees to other new kids’ properties.”

Triff sees the Workshop’s HBO partnership as inevitable. “If PBS is not able to support the kind of production budgets that kids’ producers require to compete in the marketplace,” he said, “then absolutely the Workshop will go find the best resources and distribution to do that.”

What will other producers do?

Recognition of the economic pressures on the Workshop and the limitations of PBS funding led many to question whether the network will be able to ward off other deals that could further erode the distinctiveness of its children’s service.

“There is a canary-in-the-coalmine element to this,” Kleeman said. “The biggest thing to watch is, what do other PBS producers do? Will they give first windows to other channels?”

“We should have realized that PBS’s lack of ownership of signature titles could result in the loss of control in distribution,” said James Morgese, g.m. of KUED in Salt Lake City. “We should be wary that other titles might follow.”

Triff sees the Workshop’s need for the HBO deal as indicative of a broader issue. “This goes back to the fundamental challenge,” he said, “that we are the only public broadcasting system in the world that is neither supported with enough federal dollars nor given the flexibility to generate revenue through commercial endeavors.”

As Kleeman said, “We’ve never answered the question of how we want to fund public programming.”

Public TV’s advocates in Washington, D.C., have long trumpeted the educational values of PBS children’s service, which is available to nearly all American TV households through free broadcasts, as a hallmark of public TV. PBS Kids programs reach audiences that aren’t served by commercial TV or pay cable, providing a public service that warrants government support.

Blumenauer advocates for public broadcasting during a 2011 press conference on Capitol Hill. (Photo: Current)

“I think what’s happening proves our point,” said Rep. Earl Blumenauer, (D-Ore.), who chairs the bipartisan Congressional Public Broadcasting Caucus. “We’ve long maintained that there’s no real substitute for bedrock funding that’s been provided by federal government.”

Even Sesame Street, one of the most successful franchises on public TV, “reached a point where it was not sustainable,” Blumenauer said. The Workshop courted potential partners in for-profit media and found “there weren’t a lot of takers.”

Knell, a veteran of public broadcasting’s government relations efforts through his long tenure at the Workshop and two years as NPR president, sees the case for federal funding differently — focused on the programming and community-based services provided by local stations. “In NPR’s case, that’s local coverage and programming,” he said. “In the PBS Kids space, it’s local work stations are doing in schools, such as literacy programs. That’s what we need to promote.”

Morgese disagrees. “I am very concerned that this erodes our position with Congress and the viewing public,” he said. “The message it sends contradicts what we have been communicating for decades: that cable can’t and won’t do the job that PBS can do.”

Perception of a paywall

The agreement also illustrates the emerging competition around digital distribution of children’s content.

HBO, which hasn’t been a player in children’s programming, will use Sesame Street and the Workshop’s two future programs on its on-demand services for subscribers, HBO Go and HBO On Demand, as well as its web-based subscription VOD service HBO Now. It’s also licensing 50 episodes of Pinky Dinky Doo and The Electric Company, a 1970s favorite that Sesame Workshop relaunched in 2009.

“For HBO, it’s a clever way to get young families into the streaming platform,” Knell said. “This puts HBO into a competitive frame with Netflix and Amazon Prime. It’s a coup to get exclusive kids’ content for streaming.” As part of the deal, the Workshop will remove Sesame Street content from Netflix and Amazon, both of which are ramping up the number of kids’ shows available on-demand.

PBS will continue to offer Sesame streaming at PBSKids.org, on the PBS Kids video app and on Xbox One, Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, Android TV and Chromecast.

But some pubcasters worried about the perception created by the Workshop’s decision to place Sesame Street behind a paywall.

“As upset as I was when the Workshop entered into partnership with Nickelodeon to create Noggin, at least that was basic cable,” said David Thiel, content director at Illinois Public Media. Thiel said he’s “distressed” by the idea of “giving a premium channel an exclusive window on a show created with public funds for the express purpose of serving at-risk kids.”

Others took a pragmatic view. “HBO is not exactly top-of-mind for children’s programming, and the benefit of having more new shows without the cost to PBS and member stations outweighs the price of waiting” the nine months, said Kat Worzalla, program manager at Milwaukee Public Television.

“In truth, we do wish that the nine-month window did not exist,” said Justin Harvey of Nashville Public Television, president of the Public Television Programmers Association, “but we are glad that the vast majority of viewers will continue to find Sesame Street on their local public television station regardless of their ability to pay.”

In 2015, the PBS Kids lineup has expanded to offer far more programming than Sesame Street. “There are 19 shows other than Sesame in the kids’ weekday block,” Knell said. “It’s a pretty impressive lineup, shows with big ratings like Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood and Curious George. PBS has redefined that space.”

Triff remains hopeful that public television will embrace possibilities to keep its programs financially sustainable.

“To me, there is absolutely a place for nonprofit media to act in entrepreneurial ways,” Triff said. “I’m waiting for the day when PBS is able to use its vast network to act in an entrepreneurial manner. That is the opportunity.”

Related stories from Current:

- Sesame Workshop hires three and promotes one in executive reshuffling

- Sesame Workshop trims 10 percent of workforce as financial losses mount

- Big Bird, Jim Lehrer have viewers atwitter during and after presidential debate

Questions, comments, tips? sefton@current.org

Correction: An earlier version of this post provided the incorrect year and channel for the debut of Sesame Street.

This was long the drum beat of conservatives – that niche cable would pick up the valuable assets of the public broadcasting system and then the question is “what are we left with once this occurs?” Perhaps it is time to reconsider the sheer number of stations in the public broadcasting system, each one of which functions as its own programming and fundraising unit? In the Washington DC area where I live, there are literally 4 stations that provide content into the same broadcast market. Might be time for some economizing on hard assets and investing more in public media programming.

“Sesame Street” actually premiered in 1969 on what was then called NET, the predecessor to PBS.

Thanks for pointing that out, altfactor. We will correct.