With Yellr app, WXXI seeks to engage new audiences — and help other news outlets do the same

Screenshot from video about the Yellr app.

A new citizen-journalism app aims to help connect journalists with communities around issues of local interest and find voices that might otherwise go unheard.

Community-reporting platforms aren’t new — think CNN iReport or the Curious City model now expanding under the name Hearken. But the mobile app Yellr, developed at WXXI in Rochester, N.Y., is unique, according to project manager Matthew Leonard.

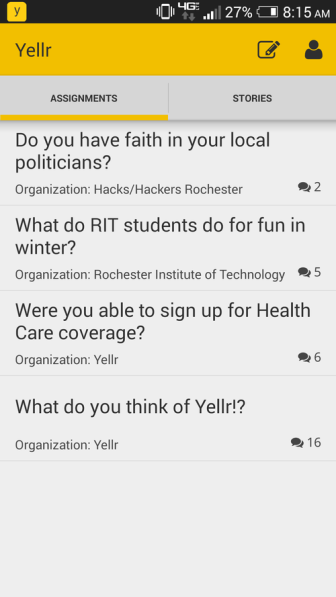

Unlike others, Yellr uses geofencing technology to target specific communities, posing questions to people based on their locations. By doing so, it aims to elevate “community conversations above the comments on a news post,” said Leonard, who also is editor of the Innovation Trail, a reporting collaboration on technology and the economy among six New York public media outlets.

Yellr moderators can add “assignments” to the app, and users can add their comments and contributions to the assignments. The contributed content could also be used on participating news sites after reviewing and fact-checking by a moderator. Commenters can be anonymous but have identification codes, allowing moderators to verify claims or comments.

WXXI has been developing the app since last year, when it received a $28,000 grant from the INNovation Fund, a partnership between the Knight Foundation and the Institute for Nonprofit News. (Current is a member of INN.) WXXI also partnered with a local developers’ group, HackHackers Rochester, to help create the app. Yellr has been available in the Google Play store since March and was added to the iTunes Store for use with Apple devices earlier this month.

WXXI completed two tests of the app with help from students at a local university, using the app to create a database of public artworks and, for the second test, polling LGBT students at the university about their views of safety and discrimination on campus.

WXXI completed two tests of the app with help from students at a local university, using the app to create a database of public artworks and, for the second test, polling LGBT students at the university about their views of safety and discrimination on campus.

The station also plans to use the app as a “key platform,” Leonard said, in an upcoming “Voice of the Voter” collaboration on political engagement with a local newspaper and television station.

So far, the app has around 250 users who are automatically sent assignments if they have the app installed and they are in a community where questions are targeted. Assignments are also promoted on social media platforms. WXXI wanted to wait to make a bigger push for users until the app was available for Apple products, Leonard said.

Rather than try to attract a lot of users, however, WXXI is focusing on demonstrating how other media outlets can use the app. This fall, five stations in New York will use Yellr for a reporting project about crime on college campuses. WBFO in Buffalo, WSKG in Binghamton, WRVO in Oswego, WMHT in Schenectady and WXXI will use the app to reach out to schools. The stations will use the app to ask questions of people near or on campus.

Now WXXI must see whether other news outlets will invest their time and money into Yellr. The app is at “that critical point of moving beyond minimum viable product,” Leonard said.

WXXI received a setback recently when it learned that it did not receive a $35,000 grant from the Knight Prototype Fund. The station will reapply, but in the meantime it will work with the Harvard Cyberlaw Clinic to develop a final terms of service, privacy policy, end-user agreement and user guide.

The partnership with Harvard “will deliver a lot of the same support for the app that we wanted from the Prototype Fund,” Leonard said.

WXXI will also rely on media outlets investing either money or staff time into developing the app if they find that it could help their work. “I’d like to see some sort of scaling up of investment from media organizations at a modest level so we could keep it open source and free,” he added.

Outlets including The Tennessean in Nashville, St. Louis Public Radio, KCUR in Kansas City, Mo.; Qué Pasa Media Network, a Spanish-language media company in North Carolina; and Maui Watch, a Hawaii digital news outlet, have expressed interest and some outlets “are looking into their own ability to support deployment around particular projects,” Leonard said.

Neldon Mamuad, the founder of Maui Watch, heard about Yellr from a news article and said he’s considering using it to help deal with the “bombardment of information” the outlet gets from the public.

Maui Watch originated “by mistake,” Mamuad said, with a group of friends posting traffic updates and road closures to a Facebook group. Maui lacks a central TV station, according to Mamuad, and the Facebook page got 8,000 likes in its first 72 hours online. So the site has community engagement built into its origins.

“People are posting directly to social media, and we are policing it” for inaccurate information, Mamuad said. With Yellr, “we can then triage what gets published or not published,” he said. “That’s where we’re hoping the app will help us.”

Mamuad was also intrigued because media outlets can start their own versions of Yellr by using its open-source code, available through GitHub. Maui Watch could use the code but promote the app with its own brand.

Investment from other newsrooms will be important for Yellr’s success, as only five people have worked on the app so far.

“Hopefully [Yellr] contributes to some reimagining of audience engagement and also brings some voices out that wouldn’t normally be engaged,” Leonard said. “I think it’s not just the technology, it’s also about the conversations that have to happen and finding how communities can tell their own stories more.”

Here’s a video overview of the app:

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified the Institute for Nonprofit News.

Related stories from Current:

Anyone interested in finding out more about the app can email yellrdev@gmail.com or download the Yellr app and send us a message, which is how Neldon at MauiWatch reached out.