Three ways podcasts and radio actually aren’t quite the same

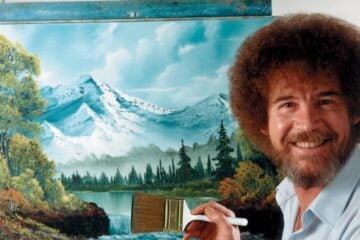

(Photo: Thomas Kamann, via Flickr/Creative Commons)

(Photo: Thomas Kamann, via Flickr/Creative Commons)

In her excellent piece for Current, “Why the push to launch podcasts is missing the point,” Michigan Radio Program Director Tamar Charney makes some very smart observations that got me thinking about the relationship between radio and podcasting in some new ways. But I think she’s a little wrong to assert that podcasts and radio are basically the same thing.

Her argument, if I may condense it and also read a bit between the lines, is that public radio managers are letting themselves off the hook by clinging to the notion that there are intrinsic formal differences between podcasting and radio.

“The real issue being voiced in yearnings for more podcasts — particularly by younger producers — is a desire for innovative content that sounds different from the classic public radio sound of Noah Adams and Susan Stamberg,” Charney writes.

After all, if there were irreconcilable differences between podcasts and radio, then managers would have a perfectly good excuse to keep airing Zombie Car Talk instead of giving one of their hip young talents an on-air at bat. “Yeah, that crazy podcast you kids do in your spare hours is great on the Internet, but it wouldn’t work on the air, so I have no choice but to keep trying to squeeze the tiniest drops out of this desiccated old sponge every Saturday morning,” such a manager might say (not that I know anyone like that).

Charney’s argument rests on the assertion that podcasting and radio are two different mediums for conveying the same type of content. And if I may extend her argument a half-inch further, managers who hide behind the fiction that podcasts can’t work on the air are just risk-averse ninnies who are neglecting public radio’s future in favor of one more safe, successful fund drive and Nielsen ratings book (my words, not Charney’s!).

I love this argument, and I agree with it. 90 percent of the way. The critique I’m about to offer is so close to an act of nitpicking that I considered not even writing it.

But I do think there are some intrinsic formal differences between podcasts and radio. Those differences have been significantly overstated, but they do exist. The medium has always shaped the message, from the Gutenberg printing press to YouTube.

Let’s look at the evolution of popular music in the mid-20th century. The standard song length was heavily influenced by the technical constraints of the 7-inch record, which can only hold about four minutes of audio per side at 45 rpm. Twelve-inch records hold about 22 minutes per side, so when both sides were filled with now-standard three- to four-minute songs, you got about a dozen tunes — the standard album format.

This format can, and now does, exist beyond the medium that originally shaped it. I bought a 10-song album on iTunes yesterday, and I doubt very much if the band considered the technical constraints of vinyl when putting it together.

Likewise, Marc Maron’s WTF podcast can be — and is — played on the radio, as Charney points out. However, I don’t think anything close to that show would have been born on the radio, for these reasons, among others:

1. Podcasts are free from clock constraints.

Unlike a radio show, a podcast doesn’t have to time out to a specific length, it doesn’t have to meet breaks at specified times, and hosts don’t have to “reset” the conversation every five minutes to let people who are just tuning in know WTF they’re listening to (pun intended). Nobody tunes in to the middle of a podcast.

These may seem like small things, but in my experience, they have a profound effect on the tone of a show. In the wild, conversations are not rigidly timed and we do not stop in the middle of them to restate who the participants are. To do so feels super-weird and always injects a formality that is the antithesis of everything a Marc Maron interview stands for.

I know of what I speak. I left full-time radio about a year ago for academia and have also been hosting/producing Current’s new podcast The Pub since January. Just today, I plunged back into the radio world, sub-hosting for pubmedia veteran Celeste Headlee on her new live daily show, On Second Thought.

Headlee values conversationality and informality above almost everything else on her show, which is why she asked me, of all people, to try filling her shoes for a day. (I’m known as a pretty laid back guy on-air.) But I don’t think I sounded very much like myself today as I negotiated a hard clock again, at least not the version of myself that I have cultivated since launching The Pub. That’s not a knock on Headlee’s show, nor am I trying to shift blame for my own failings to a set of dictatorial formal constraints. Some of us, like Headlee, are better at negotiating those constraints than other people, but they remain forever constraining.

Radio shows that seem to do best repackaged as podcasts either have spacious formats in which monologues and conversations can breathe, podcast-style (The Moth, Fresh Air), or are meticulously scripted narrative shows (Radiolab, This American Life) that, through sheer force of authorial will, can negotiate the formal constraints of radio more gracefully.

2. Most radio shows need to try to please a lot of people at once.

A niche audience cannot sustain a typical public radio station. Public radio content that does well in the ratings usually exhibits a certain predictability. Lots of different kinds of people can all get behind stuff that sounds generically “NPR-ish,” and they want to know that they can turn on the radio at any time and get something that’s more or less what they expect.

Podcasts, in contrast, can serve a much more rarified audience — people with the same peculiar interest or taste who are spread few and far between, but when united by the magic powers of the Internet form the core of 20,000+ people who collectively make a podcast commercially viable. This distinction results in content that is just plain different, and gloriously so, in my opinion.

3. Podcasts, as accessed by most consumers, are things that listeners “opt in” to.

Instead of just flipping on the radio and either loving or hating what they hear, podcast listeners usually find things they like and commit to them by subscribing. This results in a different relationship between the content creator and the audience.

Whereas the intro to an All Things Considered story needs to earn your buy-in in the first sentence or two lest you literally or mentally tune out, a podcaster whom you already know and trust can take a winding road to the point, as sex advice columnist Dan Savage usually does with the opening riff of his Savage Lovecast. Comparatively few radio broadcasters have achieved the level of trust that allows someone like Garrison Keillor to get away with telling a veritable shaggy dog story every week with his “News from Lake Wobegon” monologues.

This leads me to a concluding point, which is that podcasting is also formally distinct from other types of audio on the Internet, namely streaming. As I referenced with the link in my previous paragraph, early data yielded by the NPR One app (“the Pandora of public radio,” as NPR One editorial chief Sara Sarasohn describes it), shows that listeners who are streaming a semi-spontaneous assortment of public radio segments have little patience for content that meanders to the focus statement, and they tend to avail themselves of the “skip” button that NPR One offers them for the first time.

Listeners probably behave differently in a Pandora-like environment than they do when they pull up their favorite, weekly hour(ish)-long podcast. Of course, people can stream podcasts through apps like Stitcher that serve up a semi-randomized playlist of shows based on listener tastes. The lines between these mediums are both gray and fluid. But the lines do exist, and we need to reckon with them.

Adam Ragusea hosts Current’s weekly podcast The Pub and is a journalist in residence and visiting assistant professor at Mercer University’s Center for Collaborative Journalism.

Related stories from Current:

I’m a little confused about point three. Do you honestly believe that because users opt-in to podcasts that they are more willing to suffer through meandering hosts? If that’s the case, then podcasts must magically transform human beings who use them from busy people who value their time to die-hard fans who hang on every word. Don’t you think the same thing could happen with podcasts? Since we don’t have a whole lot of data about how much people really listen to podcasts, don’t you think you’re stretching it a bit here?

I’m a little confused about point three. Do you honestly believe that

because users opt-in to podcasts that they are more willing to suffer

through meandering hosts? If that’s the case, then podcasts must

magically transform human beings who use them from busy people who value

their time to die-hard fans who hang on every word. People who “opt-in” to online videos often “opt-out” if the video loses their interest. Don’t you think

the same thing could happen with podcasts? Since we don’t have a whole

lot of data about how much people really listen to podcasts, don’t you

think you’re stretching it a bit here?

I think Adam’s point is valid. Look at it this way: when you’re going to the movies, you’ve invested a fair amount of time and effort…psychological capital, let’s call it…and some money to go to the movie theater. Unless the movie REALLY stinks, you’re going to stick around to watch it all because of that investment you’ve made.

On the other hand, if you came across the same movie on cable TV while channel surfing, you might only watch a few seconds, maybe a minute, get bored, and change the channel. You’ve invested much less into watching that movie, and there’s much less of a penalty if you “withdraw” that investment.

Listening to the radio is like seeing the movie on cable TV, whereas the podcast is like going to see the same movie in the theater.

Granted, the analogy isn’t perfect; I agree that you can’t get away with being TOO meandering in your podcast. Poor content is always poor content, regardless of the medium. But with a podcast you DO have somewhat more freedom to expect your listeners to stick with you even if it takes time to lead up to a point. The key is that the time you take can’t be wasted time. You can’t just meander senselessly, you’ve got to have good reason to take that time to make that point.

And yes, I don’t think there’s a whole lot of empirical data on this topic, but I think the logic is sound enough that we can accept it on face value for the moment.

Yeah, what Aaron said. Also worth noting how many of the most successful podcasts start with unbelievablely long, wandering riffs about not much at all. Bad radio. And yet WTF subscribers have developed an investment in Marc and his cats that makes them listen to the latest Maron household cat drama in a way that a general audience would not.

In my opinion both this piece and the one it references miss the larger point. While podcasting and radio are not “the same” they are part of a larger whole defined by audio, where any of the audio elements within that whole can be shaped to fit the more narrowly defined platforms.

Media is defined by how it is used by consumers (and advertisers) and what the substitutes for that media are. My own research has shown that “radio” and “podcasts” share much attention in common, thus explaining why many if not most of the top ranked podcasts are radio shows.

Meanwhile, the rush to advertisers by podcasters will depend on traditional metrics – reach and engagement – that are common to (drum roll) radio. I guarantee you that when Serial was in Cannes chatting up advertisers they were sharing their big numbers. Just like…radio.

So to wrap up, the notion that these are “different” diminishes both. The idea that they are part of a larger canvas is the realization that creates the big opportunity.

Check out David Byrne’s Ted Talk on How Architecture Helped Music Evolve.

http://www.ted.com/talks/david_byrne_how_architecture_helped_music_evolve?language=en

The space does help determine the form. There are all kinds of theatre which have much in common, but stand up comedy in a bar is a very different experience than attending a performance at Lincoln Center.

I had much the same reaction as Adam Ragusea to Tamar Charney’s observations on podcasting vs. radio. Along with a germ of insight, she ignores significant differences, which Adam’s followup piece begins to elucidate. He points to (1) the lack of “clock constraints” that allow a somewhat freer approach to program content and editing, (2) the ability of podcasts to serve smaller audiences than typical radio content, and (3) to the “opt-in” subscription relationship between the listener and the show. These are all useful distinctions, but there are still other important differences.

Start with Ms. Charney’s statement that “podcasts are just a distribution technology.” Why yes, it is, but that technology enables a fundamentally different “use case” (a term from software development), one which happens to be the crux of an ongoing revolution in media. That is, podcasts enable “on-demand” use.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of this, no matter how radio professionals like Ms. Charney would like to minimize it. On-demand, global, digital network delivery of media–whether via streaming or downloading (podcasting) is a fundamental improvement in access to audio content that enables wider, deeper and more flexible engagement by a far less constrained audience. Ignore this at your peril — even television is being disrupted by on-demand access. it is a fundamental paradigm shift in media.

There are two other important differences between digital network delivery (on-demand streaming and podcasting) and radio.

First, there is no limit to the number of new shows and new ideas that can be created and delivered worldwide via these methods, vs. the strict limit on shelf space on the air, which boils down to just a handful of prime hours each day per broadcast channel, framed by vast marginal dayparts with fractional audiences. Historically this has been the biggest underlying factor in discouraging experimentation and program diversity in public radio — even with a demonstrably appealing program, it took years to gain significant carriage, even in marginal time slots and with little financial incentive.

Second (and perhaps more problematic for PDs) podcast producers do not need the approval of any professional gatekeeper to create, produce, promote and distribute these shows. They just need a good idea, some talent and the will to try it, plus a modest amount of startup money. That’s not to say that some of these producers would not benefit from professional development advice and support, but they do not have to pass through a go/no go barrier to publish.

If, as Ms. Charney concludes inarguably, “public radio needs to focus on creating great new content and engaging new audiences” it will surely be obliged to embrace the more flexible, powerful usage and delivery paradigms that Internet delivery has provided, which will change what we mean when we talk about “radio” in the future.

As Mark Ramsey points out in another comment,the larger concept of audio content is dissociating from the technical methods of delivery. Call it what you will, I believe we’re headed to a world where (with limited exceptions) any broadcast program that cannot also be accessed on-demand will be fatally handicapped.

Stephen Hill, Producer

Hearts of Space

Just another point that I always bring up when discussing this is that radio has the possibility to be live – something which a podcast never will, even if its done in one take. When one listens to the radio and it is live (which is absurdly rare these days) you get a feeling the other end of that weird radio thing is someone talking there right now – right this second! As they speak, you are hearing it in real time, its like being on the phone. They’re out there right at the moment!! There’s some kind of weird feeling of connection possible from a live show that is impossible without the, almost subconscious, knowledge of liveness. Its like going to a play vs seeing a movie, at the play there’s that little secret desire that the performers will slip up or forget their lines isn’t it? But you’ll never even expect that in a movie. Its not live!

I recognize this isn’t many people consider much anymore but its always bugged me anyway. What are your thoughts on live thing?

Isn’t everything that’s done, done live when it’s done? The phrase, for example “live in person.” The only alternative to that is terrifying. Why do we say that?

[…] https://current.org/2015/07/three-ways-podcasts-and-radio-actually-arent-quite-the-same/ […]

[…] Podcasts do not have this inbuilt marketing strength, but conversely they do have a different one: opt-in audiences, ensuring continued listenership and often word-of-mouth […]