Empathy machines: ‘This American Life’ and the public radio structure of feeling

HREDASOVA OLHA / iStock

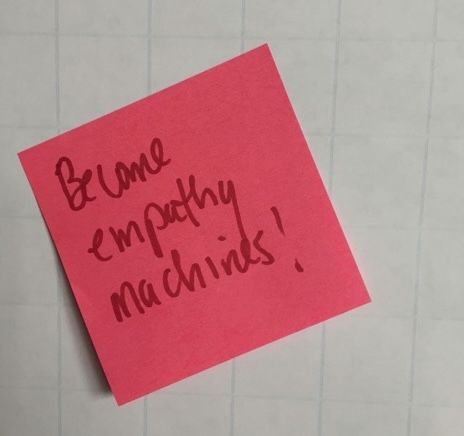

A colleague shared with me a photo of a Post-it note with the words “Become Empathy Machines!” scrawled on it, taken at the Third Coast International Audio Festival in Chicago on Nov. 4, 2016.[1] It was two days after the stunning election of Donald Trump, and one of the podcasters or producers or radio journalists had written this message in response and pasted it to a wall as part of a makeshift Post-it note mural that sprang up to collect reactions and to identify ways forward in a country that suddenly seemed strange.

At the time, I was struck by the instrumentality laid bare by the injunction to “become empathy machines!” Is that the purpose of journalism? Of art? Is that what radio and podcast producers should be in an era of rising authoritarianism and partisan rancor? Is empathy something that can be produced — like widgets on an assembly line?

Other questions followed in quick succession: Who are the subjects of empathy — the empathy havers? And who are its objects — the empathy getters? Are there other ways to conceptualize the relationship among listeners, speakers, audio media and democratic humanistic values? Compassion? Solidarity? Maybe “just the facts”?

Also, let’s be honest — many saw Trump’s first election as, in part, a massive failure of the media, public radio included. The unofficial motto of the new regime, after all, was “Fuck your feelings.” In 2016 and again last year, empathy seemed to have been defeated by angrier affects.

Only a month or so ago, Elon Musk said on a podcast — one of the biggest ones — that “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy.” His qualification was instructive: “I think empathy is good, but you need to think it through and not just be programmed like a robot.”

What’s striking here is that even those who oppose empathy make the connection between empathy and machines. For Musk, empathy was suspect to the extent it became a robotic output, a rare moment when the tech tycoon used the term pejoratively.

I should say that the Post-it note’s message wasn’t exactly surprising. At that same 2016 audio festival, This American Life producer Chana Joffe-Walt and then-New York Times journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones co-led a workshop titled “Make Them Care.” Maybe one of them wrote the note? TAL EP Julie Snyder, who also presented at the festival — on scriptural attention to storytelling needed to make emotionally compelling shows — had called radio an empathy machine only a few months later on another podcast. Maybe she wrote it?

It could have been just about anyone at that gathering. By 2016, empathy was a shibboleth of the public radio and podcasting industry and the modern liberal affects that it evoked and circulated. Not just empathy but an administrative perspective on empathy: It’s something we can manufacture.

Public radio had been explicitly understood as an empathy machine since the dawn of TAL in 1996. If we allow synonyms for empathy, radio has been understood this way since long before that. Finding a single coherent origin point for radio’s status as a “feeling medium” is a mug’s game and risks an infinite regress backwards to the first sympathetic vibrations of Nicola Tesla’s inductive coil.

And there’s a still longer history of regarding various media of communication as uniquely efficient machines for producing empathy — most famously, of course, the novel.

Before that, the printing press. Before that, oral storytelling. Think of Scheherazade’s 1,001-night campaign to survive — and humanize her captor — by telling tales. This very example has been cited by Ira Glass in his paeans to the power of empathy via audio.

More recently. virtual reality has been heralded for its powers of inculcating empathy.

Above all, podcasting has for over a decade been considered the empathy machine par excellence, which makes it all the more significant that Musk chose The Joe Rogan Experience, arguably the most successful podcast in history, to excoriate empathy.

Empathy machines

“Empathy machine” is a useful metaphor to the extent that it hits our ears as an oxymoron, the opposition between the human and the mechanical. And as a productive trope for exploring the role of media, specifically audio media, in fostering human connection, a common, if quixotic, preoccupation of media scholars, media makers and some listeners.

“Empathy machine” resonates in part because it partakes in something a bit grander — something about the promises of technology, both prosthetic and spiritual, stretching back centuries. Ghosts have long occupied machines, machines have long occupied gardens, just as golems and robots have long occupied the human imagination.

A dominant theme in media history is the role of technology as an extension of human values, such that we no longer hear the metaphors in our arguments. Just as walls and bridges immediately evoke opposite political positions, wavelengths and vibrations become easy shorthand for shared sensibility and human connection.

The idea of radio as an empathy machine stems from a specific history that has been referred to as “the technological sublime,” an impulse that can be traced back to antiquity but is critical to modern conceptions of democracy, the Enlightenment and liberalism.

The notion that we can invent and communicate our way into equality is central to the way we understand Western history since at least the printing press. The American colonies’ high rate of literacy has been suggested as the key to the Revolution’s success.[2] And the spread of public libraries, roads, schools and newspapers was fueled by early republican nationalism, which in turn was bolstered by the “deep horizontal connections” fostered by the daily press.[3] Democracy, history tells us, is a matter of horizontal political mechanisms and analogous emotional circulation.

This history is opposed by an equally compelling one in which the machine represents the antithesis of the values of democratic participation and empathy. From science fiction to folk songs to labor activism, the machine has been a reliable heavy, evoking lust, greed, envy and other sins. The machine has long served as an all-purpose foil to the human, a point of aspiration and recrimination, a metaphor of human perfectibility and corruption.

This tension helps to explain the appeal of the term “empathy machines” as a way into understanding public radio as a “feeling medium,” in Bill Siemering’s words. In his historic 1970 NPR “Purposes” document, he calls on public radio to participate in a larger “affective education,” radiating from the Great Society ambitions of its founding.

The term may also help to capture the contradictory currents of feelings and structures swirling around at the twilight of liberalism and open up ways to think about what comes next as human-nonhuman interfaces and encounters become more complex. I have in mind, for our purposes here, the increased use of artificial intelligence technology in human voice generation, on radio and in podcasting.

Empathy machine is also a useful trope for thinking about the contradictions inherent in modern liberalism, poised between humanistic principles and cynical instrumentality. It invites us to examine empathy skeptically, as a vector for complacency rather than for change. But this term, and its ubiquity, suggest that empathy may be something we can’t do without.

‘This American Life’

Above all, “empathy machine” is a useful way to think about the very particular relationship to talking about feelings pioneered by TAL and carried into many of the most popular, celebrated and impactful podcasts of the 2010s and beyond.

TAL’s explicit claim to empathy is one of the reasons I centered the show in my forthcoming book. The radio show turned podcast turned cross-platform branding juggernaut has celebrated the power of empathy over 30 years, 850 episodes, every major award in journalism, 3 million weekly listeners via podcasts and 500 radio stations and a sprawling brand that includes Hollywood films, a short-lived TV show, and partnerships with NPR and The New York Times.

TAL’s 2014 spinoff Serial, the breakout podcast global sensation, broke records for downloads and created a market for long-form investigative audio journalism. Even before this watershed moment, TAL represented an origin story of nonfiction podcasting, lending its compelling narrative style, its insinuating sonic design, its intimate vocal performances and its ambivalent political interventions.

TAL’s founder and host Ira Glass has been evangelical in his calls for empathy — it comes up hundreds of times throughout his oeuvre. “The purpose of public radio,” he told live audiences as early as 1998, “is to tell stories to make us empathize, feel less crazy and separate.”

That same year, Glass dissected his own storytelling technique as a master class in how to trick listeners into empathizing with people different from them. He gives two examples: an interview with an African American boy from a Chicago housing project who longs for a house with a basement, and a Mexican-American girl who longs for more independence. He hides the race, ethnicity and immigration status of these objects of empathy during the first part of the stories to “make you empathize — and think they’re middle class like you and me.” It’s empathy as conjurer’s trick — a rhetorical sleight of hand.

And here is where we see the first problem with this model of media as empathy machine. Empathy was produced for white middle-class listeners — something for them to consume and most of all to feel. The objects of empathy were the others — the brown, the poor, the foreign — and were regarded neither as producers of empathy nor as feelers of empathy.

TAL’s commitment to empathy and the class assumptions baked into it is wrapped up in the founding contradictions of the creation of public radio in the U.S. Pioneering NPR audience research guru David Giavannonni conceded in 1990 that this “premeditated elitism” was baked into the network’s audience measuring logic.

Another problem is the way this particular industrial model of empathy exacerbates the besetting sin of liberalism. John Durham Peters identified it as “courting the abyss,” his term for the liberal impulse to “fraternize with the enemy,” to tolerate the intolerant. Following Peters, we might say that machine-made empathy, like liberalism, “always needs to be losing itself in the other.”

We can see traces of courting the abyss in some of the show’s most historic scenes. Consider the first full episode after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, titled “Before and After.” The last act captures a few of the things that made TAL affectively compelling without being political.

In the act, WBEZ reporter Shirley Jahad describes for Ira Glass a scene in which two Chicagoans shout at each other while holding opposite ends of a massive American flag. It’s the week of Sept. 17, 2001, only days since the Sept. 11 attacks. One man is Arab-American; the other man is described, variously, as “white” and “Anglo-American.” The flag, which had been carried by two white protesters, has come quite literally between them during a street demonstration in response to the attacks of Sept. 11.

… In the crush of the crowd, somehow the other end of the flag gets transferred to another young man … an Arab-American. Now here’s the white guy and the Arab-American and they’re both holding the same American flag.

The two men belong to different groups that have been coming out every evening since the attacks to demonstrate their very different understandings of patriotism in a Chicago neighborhood near a large mosque, “one of the biggest Arab-American communities in the region.” Neither man can let down his side of the flag even as they debate its meaning and its relevance to nature of their debate.

According to Jahad, “the white guy is completely at a loss as to what to do, because he’s put in this perplexing situation. He’s holding Old Glory, and he can’t let go, but he’s holding it with an Arab-American.” The two sides are both yelling “USA, USA” but Jahad reports, with some prompting from Glass, “they mean completely different things.”

“The white guys … they’re basically saying, ‘This is my country, and we want you out of here. You get out.’” Jahad then plays some actualities from the demonstration featuring the white man holding the flag: “We’re sick of the Arabians (sic) being here and we want them out of our country.” An Arab-American man counters, “Did you know my father served in the Korean War and I’m a Palestinian? My grandfather served in World War II? Can you believe that? … This should not be happening.”

Another white man responds to questions of citizenship with, “Well, I don’t give a [bleep] whether they were born here or not. Their ancestors weren’t born here.” Amid the conflict and anger, the two men, representing opposed sides, are stuck with each other, holding up their ends of an enormous flag, a problem especially for the white man, according to Jahad. “He can’t drop it. He can’t let go of it. Because it’s the flag. So he’s got to hold it. So he holds it, and after a while, they walked together.” Eventually, Jahad tells an incredulous Glass, the two men, still holding the flag, “walked together and they actually started a conversation.”[4]

It’s a stunning scene, a tableau vivant of the country at an inflection point. It’s also an early example of TAL’s ability to bring its journalistic and storytelling prowess to bear on political conflict with as much impact as it had on stories of families and personal journeys. This scene, and all the stories in the first full post-9/11 episode, demonstrated Glass’ literary approach to understanding human communication and conflict. The episode represents a remarkably apposite declaration of intent for the show’s evolving orientation towards engagement with politics, conflict and dialogue and away from “things that were so small and personal that other journalists wouldn’t have touched them.”

Two Americans on either side of tribal hostilities, holding up and laying claim to either side of a giant flag, forced into cooperation and eventually dialogue and forward progress down the street, is an almost too on-the-nose anecdote to be credible. It captures, almost perfectly, the explicit mission of public radio and podcast storytellers in the years following the attacks: Dialogue will save democracy. And narratives about “the other” will produce the necessary empathy to enable such dialogue. Posed against the dominant worldview available at the time, a world-historical clash of civilizations, this perspective had much to recommend it.

The mission borrowed a great deal from public radio’s earlier commitments to affective education and pluralism, of course. But in its new incarnation, it signaled a self-conscious attention to the very idea of democracy and in particular the precarious hold that liberal institutions had on maintaining a functioning and inclusive civic sphere.

In the years that followed, TAL leaned into stories that centered the role of the mediator, the go-between, the translator, the storyteller, the journalist. In this way, it was the plight of liberal mediating institutions that the show began to empathize with.

In episodes like “Lost in Translation” (2003), “By Proxy”(2007), “Shouting Across the Divide” (2006), “The Bridge” (2010), “Surrogates” (2013) and “Stuck in the Middle” (2014), mediation itself is the protagonist.

“It’s hard to be in the middle,” Basim, an Iraqi interpreter for the U.S. military, tells Glass in a 2007 interview. The episode “By Proxy,” like other shows in years after 9/11, features stories of “people substituting themselves for other people, and the difficulties that can create.”[5]

Basim describes for Glass a 2004 incident where he had to lie to achieve the best outcome in a tense standoff between U.S. soldiers, Iraqi police and an angry crowd of citizens. Glass, ingenuous, marvels that “It’s not just that you’re just interpreting what’s going on, but in a sense, you’re taking over for whoever’s in charge.”

In other words, it is the tellers of the stories, the makers of empathy, that can move us beyond an impasse. This is a recurring theme across many of the stories.

Glass is keen to generalize the experience of becoming a proxy:

It happens with friends. It happens in business settings. It happens in politics. And when it happens, things can get very confusing. When you really step in for somebody else, substitute yourself for somebody else, it can be hard to tell if you’re doing the right thing at all.[6]

Translating, serving as a proxy, finding oneself betwixt and between is both universal and very specific to the communicators working in a war zone. While the stakes are wildly asymmetrical, the show emphasizes the feeling of uncertainty and ambivalence animating all proxy work.

In this way, TAL’s stories about conflicts became stories about media and mediation. And in episodes with multiple stories, empathy’s sideways movement rippled across wildly different subjects and social situations. It is precisely because affects are “sticky,” as Sara Ahmed tells us, that these juxtapositions work. Affects don’t reside within us, Ahmed writes, but instead stick us together in transient social bodies.[7]

And the work of mediation — the work of balancing, translating and representation — becomes structural and aesthetic rather than political or moral. There is a resulting flattening of difference. The xenophobes who hate Muslims are structurally identical to the patriotic Muslims who love America.

And the proxy work of the Iraqi translator and the mediating work of the public radio host are structurally similar as well, each churning out widgets of empathy essential to the neoliberal order.

The sublimation of real-world conflict into the play of opposites is structural and profoundly reluctant to the idea of taking sides, an increasingly dangerous formula now audible on NPR’s podcasting streams and on the Joe Rogan Experience alike, where science and conspiracy theories sit comfortably side by side.

It has been instructive to listen to TAL’s changing sound over the last 10 years, a period of rising partisan rancor and a creeping disillusionment with the promises of neoliberal market logic. Mediating across the abyss has given way to acknowledging the persistent hurts of history and their centrality to various American lives.

This spring, TAL featured an hourlong exploration, titled “How to Tell a Dumb American Story,” of police neglect of Native American victims of violent crimes. It’s narrated entirely by reporter Sierra Crane Murdoch and features little of the show’s signature mood music and cutaways for grand statements. The story has a double frame. Inside the empathy machine frame, we learn that the parents (who lost their daughter, Mika Westwolf, to a hit-and-run by a white supremacist on meth) are cannily working their own empathy machine: “Americans are dumb,” Mika’s dad says. “They need a simple story … the perfect victim and the perfect villain.”

“How to tell a Dumb American Story” is the story of the besetting sin of TAL, only now with a layer of sardonic wit, characteristic of many Indigenous and minority encounters with white institutions.[8] The story keeps threatening to fall apart as Mika’s parents dispute the ethics and the feeling of using this kind of instrumentality to win a verdict versus using the case to tell a bigger story of institutional injustice.

TAL and its podcast progeny, like Serial, have increasingly leaned into these complicated, uncomfortable and layered stories, with unstable and asymmetrical moral logics. Stories that dismantle the empathy machine while still flying it require new voices and new perspectives — and TAL has managed to de-center Ira Glass’ white, male. middle-class sensibility with equal parts grace and awkwardness.

TAL’s preoccupation with empathy and with talking about how to produce it met with rare success in ways that we are now better positioned to explore, even as many of the podcasts that took up this approach have faltered or shifted into new emotional and social paradigms.

And so now, as we face what feels like a uniquely illiberal moment in our history, it seems a good time to examine the institutions of modern liberal feeling — like public radio and nonfiction podcasting — to better understand how we got here. And to see if our reliance on media and other liberal institutions as empathy machines is still the way to go — or if it ever was.

Jason Loviglio teaches media studies at The University of Maryland, Baltimore County and co-edits Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media. His book Empathy Machines: This American Life, Podcasting and the Public Radio Structure of Feeling will be published by Bloomsbury Academic in January 2026 and can be pre-ordered now.

[1] Thanks to Neil Verma for taking this photo and knowing it was the perfect thing to share with me.

[2] Stephen Earl Bennett, Staci L. Rhine, and Richard S. Flickinger. “Reading’s Impact on Democratic Citizenship in America.” Political Behavior 22, no. 3 (2000): 167-95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1520046.

[3] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, 2nd edition. (London, England: Verso Books, 2016).

[4] Glass, Ira. “Before and After,” This American Life. Episode 194. September 21. 2001.

[5] Glass, Ira. “327: By Proxy,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, 9 March. 2007; —- “238: Lost in Translation,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media,30 May. 2006; — “485: Surrogates,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, 25 January. 2013; — “322: Shouting Across the Divide,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, December 16. 2013; — “407: The Bridge,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, 10 May. 2013; — “516: Stuck in the Middle,” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, January 14. 2014.

[6] Glass, Ira. “327: By Proxy.” This American Life. Chicago Public Media, 9 March. 2007.

[7] Sara Ahmed. 2004. Social Text. 22 (2 (79)): 117–139.

[8] Barre Toelken 2003. “5 Patterns and Themes in Native Humor.”Anguish Of Snails: Native American Folklore in the West. Utah State University Press. 146-164.