LAist’s ‘Inheriting’ podcast aims to shed light on Asian American and Pacific Islander history and community

LAist

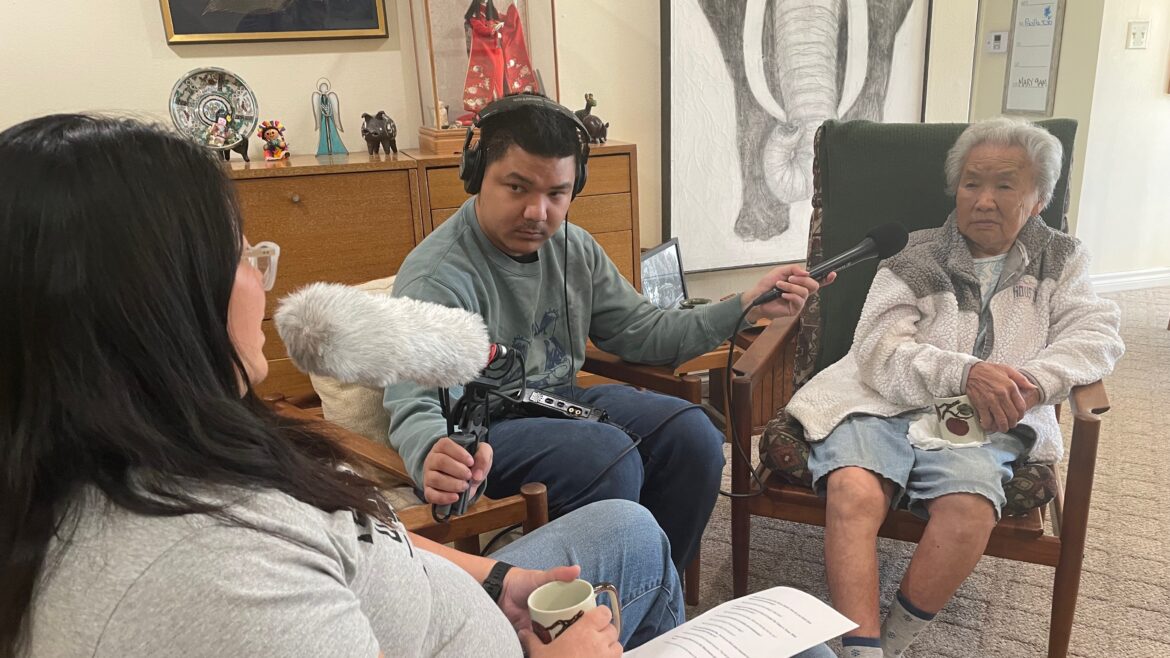

"Inheriting" producer James Chow records a conversation between Leah Bash and her aunt Haru Kuromiya about Kuromiya's memories of Manzanar, a war relocation center for Japanese Americans.

A new narrative podcast is attempting to bridge the gap between the personal and the historical by shining a light on the stories of seven Asian American and Pacific Islander families from California.

Inheriting, a production of LAist Studios distributed by the NPR Network, finds Emily Kwong, host of the NPR podcast Short Wave, facilitating conversations between family members about everything from the 1992 Los Angeles uprising to the Imperial Japanese occupation of Guam to what it was like to grow up under the brutal thumb of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. By sharing deeply personal, long-held emotional truths, participating families are able to better connect and understand each other, as well as better process their place in human history.

Much of the history covered on Inheriting isn’t typically taught or told, whether in schools or within AAPI communities, and much of it is also shockingly recent, happening within the last 50 to 100 years. These are stories that remind us that history happens every day, often to people we know and love.

“Pretty much every Asian-American and Pacific Islander person walking around is just two or three generations away from the kinds of events you see on the news, like conflict, displacement and family separation,” says Kwong, who notes that while the news media is typically pretty good at covering tragedies and emergencies when they’re happening, it doesn’t always circle back to understand the aftershocks of those events years or generations later.

These crises often affect the mental health, behavior and relationships not just of those initially impacted, but also their families. “People should have the opportunity to talk openly and to heal,” says Kwong. “Research has shown again and again that identifying with your community or your ethnic group can be really good for your mental health, especially for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, who are the least likely of any racial or ethnic group to seek out mental health services.”

Growing up in suburban Connecticut, Kwong says, she rarely saw families that looked like hers or that might have had similar family histories. “That kind of ‘otherness’ does things to a person,” she says. “The most powerful healing I’ve found over the years is connecting with other Asian Americans about their family histories and mental health struggles. I took that discovery and made a show about it.”

The birth of ‘Inheriting’

Inheriting grew out of strong listener and donor support at LAist. The Pasadena station has been committed to telling stories about the region’s AAPI communities for years, with reporters like Josie Huang focusing exclusively on that beat.

LAist has made a point of developing strong bonds with the local AAPI community, nurturing connections with sources and organizations as well as donors. In 2021, one of those donors — whom the station is declining to name at this time — stepped up with a significant amount of funding earmarked for telling AAPI stories.

The station asked staff for pitches, and producer Anjuli Sastry Krbechek responded with Inheriting, which she co-created with Kwong, an old co-worker from NPR. The show was picked to receive that initial round of funding in 2022, and after the station presented the concept to additional donors, those individuals filled in the rest of the show’s proposed budget.

Starting in 2023, the show assembled an all–Asian American production staff, pulling in senior editor Sara Sarasohn, producer Minju Park, EP Catherine Mailhouse and producer James Chow under the supervision of LAist Studios VP of Podcasts Shana Naomi Krochmal. The team put out an open call to listeners for stories and worked with LAist’s community engagement team to reach out to over 150 local AAPI community organizations asking about the stories they wanted to hear told, as well as for recommendations about which families might have something to say.

Ultimately, the show received about 100 solid pitches for ideas. After a few rounds of interviews and eliminations, producers settled on seven local families from countries around the AAPI diaspora including Cambodia, Guam, Japan, India, Korea, Pakistan, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Given that the AAPI umbrella covers over 50 different ethnic groups speaking over 100 languages, Inheriting is specifically focused on telling the stories of individual families, rather than implying that these individuals speak for everyone or for what Mailhouse calls “the AAPI monolith.” The show tried to find individuals who were seeking answers to very specific questions about their family’s past, with each episode focusing on the relationship between the participants rather than the historical details of the incidents covered.

The show’s producers also took pains to diversify the areas of California they covered, recording in 20 different cities and taking listeners to places like the Khemara Buddhikaram Buddhist Temple in Long Beach, one of the largest Cambodian Buddhist temples in the U.S.

“We tried to honor each community in a personal way,” says Krbechek. “We were very intentional in the selection of folks in terms of which neighborhoods we were representing and where those communities were located, and we wanted to tell our stories by visiting those places instead of doing all the work virtually.”

Mailhouse, who’s also director of content development at LAist Studios, says that for her, Inheriting is about not just good storytelling, but also about building community. “This is not a show that exists in an echo chamber,” Mailhouse says. “It’s about challenging myths and prejudices and grappling with our own very complicated histories, traumas and issues, but it’s also about reaching out to people outside of our own community and understanding what those dynamics are.”

Addressing intergenerational trauma

While making its episodes, the Inheriting team also took great pains to honor and support its subjects, conducting multiple pre-interviews with candidates about what was to come, what they’d be comfortable opening up about and what was off the table.

The show had a consulting psychologist, Sherry C. Wang, whom Kwong knew from her work as co-founder of NPR AZNs, an employee resource group for Asian Americans working at the public radio network. Wang helped the team hone how they talked about trauma, as well as how they could develop the right questions to ask. Additionally, the staff trained with the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma at Columbia University about how to do adequate reporting for each story, as well as how to ask sensitive questions appropriately.

Doing each interview, Kwong says, was an intentionally deliberate process. “The person leading the interview was someone related to that individual, and they shaped the questions,” she says. “We took a lot of breaks, we ate food, we hydrated, and we broke up the conversation sometimes into two or three interviews.”

They also let the interviewee shape the conversation, like in the case of Khmer Rouge survivor and episode three subject Bo Uce, who lost both of his parents and his baby sister to the regime. Uce told the Inheriting team that there were just some places he didn’t want to go on tape. His daughter, Victoria, decided to just focus on three aspects of his story for their taped chats: How her dad felt as a child under the Khmer Rouge, how he grew up with violence and chose to live with compassion, and what kind of parent he wanted to be.

On the podcast, Uce says he agreed to do the show because he appreciates how much his daughter’s generation loves, nurtures and cares for humanity. He’s heartbreakingly frank about a lot of the awful stuff he went through as a child. He also admits to being “a bit uncomfortable” when talking about his mom and baby sister, whom the Khmer Rouge took and presumably killed when he was 7.

“I loved my mom,” he says on the podcast, clearly holding back tears. “They took her in 1977, and I didn’t have a chance to say goodbye.”

With no adults around to explain where his mom and baby sister had gone, Uce and his three siblings could only hold out hope that they would return one day. But as Uce tells his daughter and Kwong on the podcast, they never came. He and his older brother were seized and forced into a mobile children’s brigade, assigned to do menial manual labor all over the country.

The kind of candor the Inheriting team got from Uce and his daughter was made possible only after hours of pre-interviews and chats with the subjects, which helped build a rapport that showed the show’s producers were respectful and caring, as well as committed to the subjects as individuals. That mentality even continued beyond each interview, with Wang providing resources to help subjects do more processing or find their own therapists, and producers circling back days, weeks and months afterward. Krbechek estimates they gathered about 40 hours of tape of each subject, including pre-screening, pre- and post-interviews, and the actual chats they had for each episode.

“We wanted to know how they were doing, what was going on, and if they were taking care of themselves,” Krbechek says. “It wasn’t for the story. It was just to check in, because we know that asking those kinds of questions might have changed their lives in a certain way, so we wanted to make sure they had the resources they needed.”

The show also plans to publish resource guides for the public on its LAist landing page, including materials that informed the writing and reporting of each episode as well as supplemental material about the region’s AAPI communities. “We want to also make sure that we pass on the knowledge that we gained so that others can sit down with their family members and have a conversation about their histories and their experiences,” says Mailhouse.

Moving forward

While Inheriting just debuted Thursday, LAist has held special listening events for donors and community organizations, all of which have garnered a significant response. Mailhouse, who has worked in news for over 20 years, says the response the show received at those events was unlike anything she’s ever seen

“We have received visceral, very emotional responses during listening events, even when the show was still a work in progress and we were playing very short clips, like one or two minutes long,” she says. “People were crying and coming up to us wanting to say how the show resonated with them and how they wanted to tell their story.”

Calling Inheriting “the show that the community wanted and the show that my teenage self wishes that she had,” Kwong says she’s especially proud of the show’s 40-minute length and pacing. While media is trending toward shorter pieces, quicker podcasts and bite-size content, Inheriting makes a point of slowing down and digging into each story.

“I actually feel like this might be more of what people need,” says Kwong. “It’s certainly what I need to feel like I’m actually connecting to other people and deepening my own understanding, or maybe checking my assumptions at the door instead of having quick takes and sound bites and easy feelings. The emotions in the show are complicated, and it’s going to challenge people who listen to it, but those who stick with it will be taken on a ride.”

As for future plans, the possibility of a season two hangs on whether LAist can fund it. Kwong says that the team has kicked around doing a series of episodes that looks at history through food culture, but since the show is entirely donor-funded, actually making those episodes will require some listener buy-in.

Mailhouse is confident they’ll get it, though. “It’s just a matter of trying to get as many people as we can to be aware that this show exists,” she says. “People just need to hear this show, and the support and the donations will follow.”

Corrections: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that the families in the podcast are from Southern California. One is from Northern California. It also incorrectly referred to the Buddhist temple in Long Beach featured in the podcast. It is the Khemara Buddhikaram Buddhist Temple, not the Wat Buddhavipassana temple. And it used an incorrect name for the employee resource group for Asian Americans at NPR. It is NPR AZNs, not NPR Asians.