Bob Edwards, first host of NPR’s ‘Morning Edition,’ dies at 76

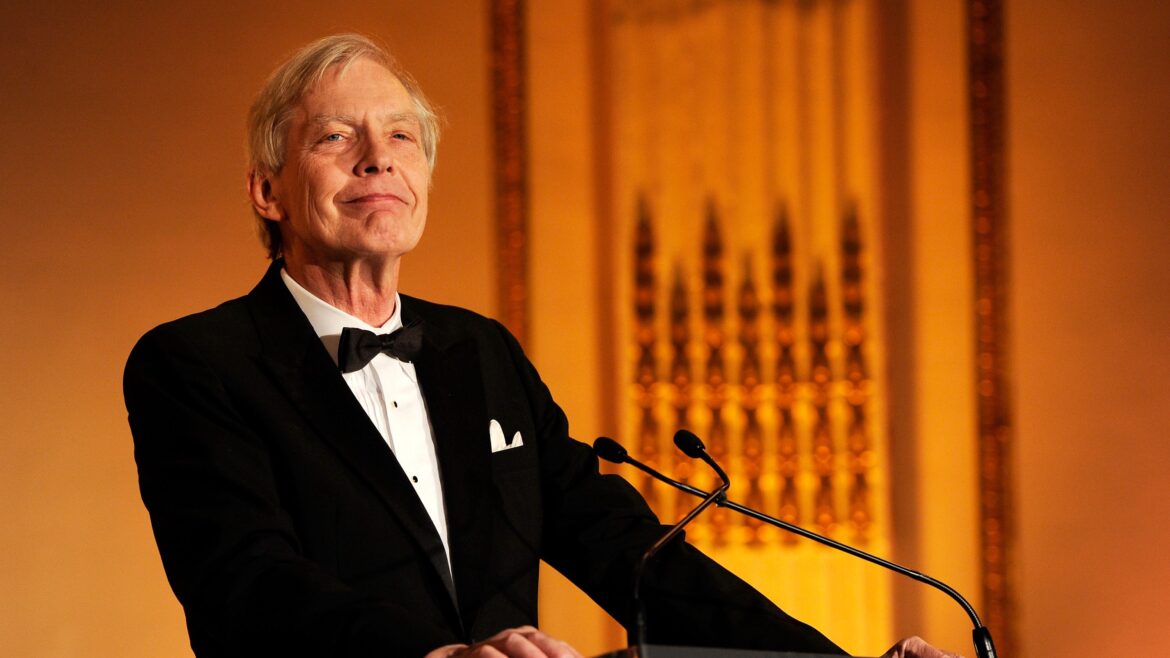

Larry Busacca / Getty Images

Bob Edwards at the AFTRA Foundation's 2012 AFTRA Media and Entertainment Excellence Awards at The Plaza Hotel Feb. 6, 2012, in New York City.

Bob Edwards, the first and longest-serving host of NPR’s Morning Edition, died Feb. 10. He was 76.

He died of congestive heart failure and metastatic bladder cancer, his wife Windsor Johnston told Current.

Edwards listened to NPR “up until the day he died,” she said. On his last day, he and Johnston listened to Wait, Wait … Don’t Tell Me!, and she played him the original Morning Edition theme. He didn’t talk much that day, but he smiled and shed a tear when she played the song, she said.

“He was so proud of Morning Edition, and he was proud that he was able to help pave the way for what it is and what it still is today,” said Johnston, an NPR newscaster and reporter.

Edwards got his start at NPR in 1974 as a newscaster and went on to co-anchor All Things Considered. He began hosting Morning Edition in 1979 until he was reassigned in 2004, which sparked a backlash from listeners.

Edwards was “one of the great voices and talents of this network’s history,” NPR CEO John Lansing said during an NPR board meeting Tuesday. “Bob helped shape the sound of NPR. He understood the intimate and distinctly personal connection with audiences that distinguishes radio and audio journalism from other mediums. In his 24-and-a-half years as host of Morning Edition, he helped launch and define what would become our network’s most–listened-to program.”

Edwards had no hosting experience when he began co-anchoring All Things Considered with Susan Stamberg, she recalled in an interview with Current.

When Edwards started on the show, he “didn’t know how to do an interview, and he just sort of didn’t get it,” she said. “… But he had that voice. And I have to say, that voice and the love of news and love of radio, that really carried through.”

His voice had “such a warmth to it. It was so deep and … believable,” she said. “… He was unflappable. With breaking news, he was real steady.”

When he went on to host Morning Edition, Edwards “boosted our audiences because everybody wakes up, everybody wants an alarm clock,” she said. “And Bob was the alarm clock.”

‘Bob had credibility’

Jack Mitchell, the first producer for ATC, paired up Edwards with Stamberg on the program. “I decided that we needed somebody solid to complement her,” said Mitchell, now emeritus professor of journalism and mass communication at the University of Wisconsin.

Stamberg was a “strong personality,” and Mitchell said he thought “we needed as a co-host somebody who was absolutely solid and didn’t have that much personality, wasn’t particularly polarizing, was a little bit boring. Not to put him down, but just because we needed that balance in the program.”

In the early days of NPR, “we were a bunch of amateurs,” Mitchell said. But “Bob had credibility,” which the organization needed, he said. “His great asset was the voice, its unflappable delivery. He was almost artificial intelligence” and “totally reliable,” Mitchell said.

When Edwards moved to Morning Edition in 1979, the plan was to borrow him to get the show up and running after early pilots of the program flopped with stations, said Jay Kernis, an early producer at NPR who was on the committee to create what became Morning Edition.

In the early days of Morning Edition, “Bob was a rock,” said Kernis, now a producer for CBS’ Sunday Morning. “Bob was calm. Bob was always like, ‘This is going to happen. We know how to do this.’”

Starting up the show was “an enormous amount of work,” Kernis said, “much more than we thought.” But a few years after launch, “it looked like it might actually succeed,” he said. “And that’s all on Bob’s shoulders. Because he spoke with authority, because people were very happy to have him in the morning … and he was a very reassuring, trustworthy voice.”

“Bob represented much more than just Morning Edition,” Kernis said. “He represented the promise of public radio every day. We’re going to inform you, we’re going to make you smarter, we’re going to make you more interesting.”

Outside of his work on Morning Edition, Edwards had “very little patience for NPR managers and their decisions,” Kernis said.

“There was always an executive who wanted to cut the budget, or there was always an executive who said, ‘Do you need that many staff members?’ or ‘Here’s how we’re going to change the show.’ And if he disagreed with those decisions, he was vocal about that, and I know staff members appreciated that,” Kernis said.

Kernis later became one of those executives as NPR’s SVP of programming. “At that point, I also became an idiot executive.” But Kernis said he “understood what [Edwards] was going for. He was protecting his staff, and he was protecting the show.”

‘Master of the short and quick question’

Edwards also helped create the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists unit at NPR, former NPR correspondent Howard Berkes told Current in an email. He spoke up against policies he thought were unfair, such as a contract policy in the early 1990s, which led to a challenge from AFTRA, he said.

The challenge “resulted in a settlement that included thousands of dollars in back pay and benefits for many of the reporters, and the conversion of each to full staff pay and benefits,” Berkes said. “Bob Edwards initiated the effort and helped get it to an extraordinary result – two dozen reporters finally getting fair pay and treatment for the work they were already doing.”

Berkes called Edwards the “master of the short and quick question that produced compelling and deep answers. Sometimes a single word: ‘why?’ No pontificating before getting to a question. No long background showing he knew the subject. No making the question about him in some way. He got right to the point, which often put his interview subject on the spot.”

In 1999, Edwards won a Peabody Award. “His is a rare radio voice: informed but never smug; intimate but never intrusive; opinionated but never dismissive. Mr. Edwards does not merely talk, he listens,” the awards organization said on its website.

In 2004, Edwards was unexpectedly reassigned and removed as host of Morning Edition. Kernis, who was SVP of programming at the time, said that the decision was intended to improve the show’s coverage by making way for a dual-host format. He said Edwards had insisted on hosting solo. After his removal from the show, Edwards told the Los Angeles Times that he had previously told Kernis that the show should not be co-hosted.

NPR received 28,000 emails and letters protesting the decision. Kernis said at the time that he “received the most uncivil mail that I have received in my professional career.”

“He was very hurt by it,” Johnston said. “… Bob had never gotten over … the way it was handled.”

Edwards left NPR in 2004 to host The Bob Edwards Show for SiriusXM later that year. The show ran for nearly a decade, and a repackaged version, Bob Edwards Weekend, aired on public radio.

Edwards graduated from the University of Louisville in 1969. He was then drafted and sent to work in South Korea for Armed Forces Radio and Television, according to the New York Times.

Before joining NPR, Edwards received a master’s degree from American University and worked at WTOP in Washington, D.C.

Johnston said she is in the “very beginning stages” of planning a memorial at NPR headquarters that she expects to happen in late March or early April.

Edwards will be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that SiriusXM’s The Bob Edwards Show aired on public radio. A repackaged version of the show did. An earlier version also said that Edwards did not want a co-host on Morning Edition. The article has been updated with additional details about Edwards’ statements on the issue.