Station town halls on racial justice go virtual amid coronavirus concerns

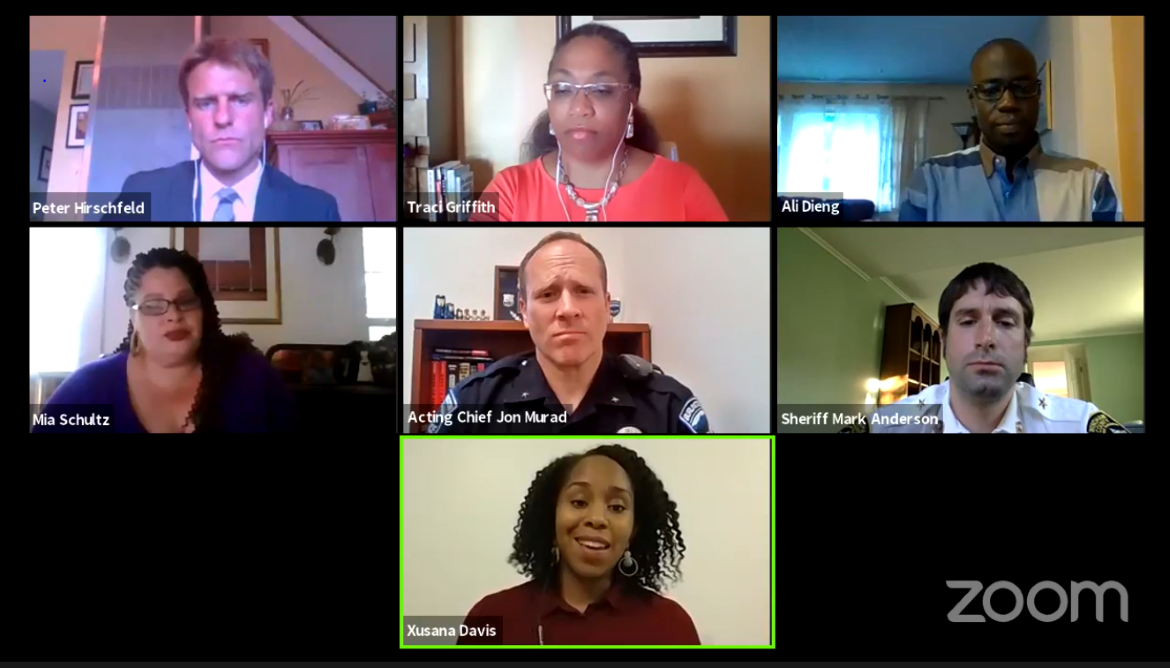

Vermont PBS and Vermont Public Radio teamed up to convene a Zoom panel June 18 on race and policing in Vermont.

The convergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide protests around racial justice is pushing public media stations to move town-hall discussions online as a way to keep participants safe while still engaging with their communities.

Moving such conversations out of studios and auditoriums and onto Zoom can involve technical difficulties and exclude audiences without internet access. But stations are also finding that the virtual format broadens the reach of the events to everyone online, even beyond the reach of their broadcast signals.

Stations including Lakeshore Public Media, WITF, Vermont PBS and Vermont Public Radio have held virtual events in response to the Black Lives Matter movement and protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd. The town halls featured panels of community organizers and leaders, with listeners getting a chance to pose questions as well.

“We talk about the lack of civility in our communities,” said Lakeshore Public Media CEO James Muhammad. “People need to see examples of that and those conversations take place.”

It’s also important for public media stations to use their platforms as a “safe and respectful space” for such discussions, said Vermont PBS Producer David Littlefield.

“It’s important for stations to understand their role in their community and if it’s appropriate for them to use their influence and space to promote these kinds of important conversations,” said Littlefield. “They should consider the risks but really be willing to take a step forward and be that platform where people can have a voice.”

Drawing on past experience

Lakeshore Public Media was one of the first stations to hold a virtual town hall on racial issues with a June 9 event. The hourlong panel was moderated by WBEZ reporter Michael Puente, who also hosts a weekly show on LPM’s radio station. Panelists included community leaders, political officials and a former Lake County sheriff.

The conversation centered on topics such as how the George Floyd protests compare to past movements, the role of the government and the faith community, what police departments are and should be doing, and defunding the police.

Puente led the discussion by targeting questions at specific panelists. Though he didn’t directly ask viewers’ questions, he at times shifted the discussion based on comments from a Facebook Live stream.

The station in Merrillville, Ind., previously held a three-part conversation series about policing and racial justice in 2016 and 2017. Muhammad said that with the past series in mind, it was “an immediate trigger” for him to restart the series after George Floyd was killed. The station was able to stage this month’s discussion so quickly in part due to its earlier experience, Muhammad said.

“If we don’t do this critical work as public media, there’s no one else here who will,” Muhammad said.

LPM aired the Zoom conversation live and streamed it on Facebook and Passport. LPM chose Zoom because it was “most familiar” to panelists, Muhammad said, but the station also recognized technical issues had to be taken in stride. The station prepared panelists by telling them the host would cue them to speak and that sometimes the conversation would have to be moved along.

Muhammad said the initial response to the panel was largely from people wanting to know how they could get involved with the issue. Panelists received emails within hours of the airing from audience members volunteering to help, which Muhammad said was one of the event’s goals.

“For people to witness a conversation in their community and be inspired, that’s what we’re trying to do in public media,” said Muhammad.

LPM plans to continue holding virtual town halls, possibly featuring panels of young adults and law enforcement representatives, among others.

Muhammad said other stations considering holding a virtual event focused on racial issues should approach the subject with respect and sincerity.

“I don’t approach it with a preachy mindset of ‘I want people to come on here and say this or that,’ and I don’t want to try to inject my personal convictions,” said Muhammad. “… It’s very important to me for things to be locally inspired.”

Not a ‘one-and-done conversation’

WITF launched a series of six conversations about systemic racism in Pennsylvania June 18. The first event was hosted by Charles Ellison, a host at WURD, the only Black-owned talk radio station in Pennsylvania. Panelists included community organizers and activists. The event lasted over an hour and a half.

Panelists discussed topics such as defining systemic racism and its role as an oppressive structure, the importance of this moment in the racial justice movement and how to build on it, the role of educational institutions, and handling collective trauma and grief.

The beginning of the event featured an animated video defining systemic racism. Listeners submitted questions during the event via Twitter, email and the YouTube Live chat. Ellison read several questions throughout the event, such as what white people can do to dismantle systemic racism.

The series will stream biweekly for 12 weeks. Heather Woolridge, director of community engagement at the Harrisburg, Pa., station, said the team behind the project “didn’t want it to be a one-and-done conversation.”

WITF formed an organizing committee for the series made up of a station board member and community leaders, who chose panelists for the first conversation and brainstormed the series’ topics.

Woolridge said WITF chose YouTube Live as the streaming platform because it was the most accessible for live participation, but the station plans to livestream the next town hall on Facebook Live as well to reach a wider audience. WITF did not broadcast the town hall, but Woolridge said the project team hopes to incorporate parts of the conversation into the station’s daily radio talk show and future long-form radio pieces.

During the livestream, viewers used the YouTube Live chat to connect with each other about resources and ways to help. Woolridge said seeing viewers make those connections was “surprising but wonderful” and that she plans to specifically encourage it next time.

WITF will also build a resource page to accompany the series that will include a reading list, prompted by a listener’s request during the stream for book recommendations, said Woolridge.

Enlisting the help of community leaders with the organizing committee was “essential” to the series’ success in its beginning stage, Woolridge said.

“We’re learning a lot through this process, and it’s important that WITF has made the commitment to make this an ongoing project that’s just now starting,” she said. “We’re hoping it will grow and evolve to something even bigger and more meaningful.”

Worth the risk

Vermont PBS and Vermont Public Radio teamed up to air a virtual town hall June 18 on race and policing in Vermont, hosted by VPR reporter Peter Hirschfeld and Traci Griffith, a journalism professor at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vt. Law enforcement officers, political officials and community activists made up the panel for the event, which lasted over an hour and 20 minutes.

The hosts asked both viewers’ questions and their own. The conversation focused largely on policing in the state, with discussion of racial disparities in police treatment, defunding police, allowing officers in schools, and internal actions police departments can take.

Vermont Public Radio focused on the editorial content, and Vermont PBS organized the video and graphics. Littlefield of Vermont PBS said the stations used Zoom because it gave the most control over the platform’s functionality. Zoom’s ability to record the individual panelists simultaneously allowed producers to smooth over audio in post-production.

Streaming the event on Facebook Live made it easier for people “to stumble across it,” Littlefield said.

Viewers were not able to speak during the Zoom, and only hosts and panelists could see their comments. Littlefield said the producers made this choice to avoid inappropriate comments and to keep the conversation civil. Viewers could ask questions in the Zoom and Facebook chats and via Twitter, where producers monitored them and chose the best for hosts to ask.

Viewers were also told that producers would remove them from the chat for inappropriate comments. No one needed to be removed during the conversation, but the Zoom chat was “very busy,” said VPR Managing Producer Lydia Brown.

Brown said the stations’ goal for the event was to create a thoughtful conversation and a space where community members could share concerns. Not setting an end time for the event “allowed the conversation to breathe,” she said.

Littlefield advised other stations considering town halls to practice with the virtual platform as much as possible. It’s also important to have test runs with panelists and to teach them the basics of virtual presentations.

Brown said stations should recognize the significance of these events, even with the risks involved.

“Something like this does involve a lot of risk,” said Brown. “So be willing to take those risks, because these are important conversations to have.”