Fans of Joe Frank remember the storyteller’s dark sonic magic

Stephen Laufer

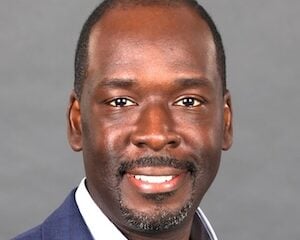

Frank in the studio.

For a city dweller like me, it’s darn near impossible to have a driveway moment in an actual driveway.

The one I have had took place in 2000 while I was producer-in-residence at KCRW in Santa Monica, Calif. One afternoon I was floored by a short piece Joe Frank produced for the station’s pledge drive. It was a twisted parody of one of those calls commercial radio stations make to a lucky listener. “You’ve just won a new car!” Or “You’ve just won $10,000 in cash!”

But Frank’s take on that pop-culture moment included unexpected drama. When the lucky soul was informed of an all-expenses-paid trip to Hawaii, it quickly devolved into the radio listener confiding that she was terminally ill. I couldn’t believe my ears.

That’s how to sum up the radio career of Joe Frank, who died Monday at the age of 79 in Beverly Hills, Calif. Many leading lights in public radio will tell you that, even if they work in nonfiction radio, Frank profoundly influenced their careers simply by demonstrating radio’s potential as an art form.

How to describe the sonic magic Frank created in 40-plus years on the air? One could say that he delivered mesmerizing monologues over instrumental music, sometime mixing in contributions from friends and actors he had recorded. But many of his admirers resort to the suggestion, “You just have to listen to the work.”

Frank’s productions often featured his confessional rambling. They were cathartic and, he hoped, therapeutic. Known for mixing fact and fiction in narratives that often drifted into the surreal and absurd, his goal was to create a transcendent experience for listeners.

In 2003, the year he was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Third Coast International Audio Festival, Frank appeared on Fresh Air and made no bones about the goal of his radio work: to do something that has never been done before. Most of his fans would say he succeeded.

Anyone who tells stories on radio “knew who Joe Frank was probably before they even knew they wanted to get into radio,” said Montana-based independent producer Barrett Golding, who has compiled remembrances of Frank and samples of his work. “And I would guess that one of the reasons they wanted to get into [radio] is because Joe Frank demonstrated what could be done.”

Golding was an engineer at NPR when met he Frank in 1985. “Nobody had ever read in such a dark, engaging fashion over music,” Golding said. “Really, he’s not much different than Jean Shepherd. He’s just a whole lot darker. It’s the same thing: a single voice in the night.”

“What Joe did with sound design, the loops he would make, the drones he would create, the space he would create before he started talking and while he was talking, I think has always been embedded in my work,” said Chicago-based filmmaker D.P. Carlson, whose documentary Joe Frank: Somewhere Out There is expected to screen at festivals this year. Carlson started listening to Frank in 1988 on Chicago’s WBEZ while he was in college and views Frank as one of his mentors.

“There’s a scene in my film where a guy came up to him at an autograph table and says ‘You made me want to do better work,’” Carlson said. “And I think a lot of people who are into Joe Frank realized what a great artist he was. He forced us all to think about getting the best out of ourselves.”

Carlson’s documentary chronicles a traumatic life that has included a series of medical struggles. Frank was born with clubfeet and later had three bouts with cancer and kidney failure.

Frank’s parents were Holocaust refugees. His father died when Frank was young. Frank’s mother remarried and fought viciously with his stepfather, whose surname he took. The young Frank started writing about the domestic strife, launching his career observing and commenting on the human condition. Later, he would surreptitiously record phone conversations with friends.

Frank earned a bachelor’s degree in English at Hofstra University, where one of his classmates was Francis Ford Coppola. Afterwards he attended the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop and took a job teaching at an elite private school in Manhattan. He found his way to Pacifica station WBAI-FM in New York City, where he started hosting a freeform show in 1977.

“From the very start, I knew he was a unique voice with a very dark sense of humor,” said David Rapkin, a Grammy Award–winning audiobook producer and director who served as Frank’s engineer at WBAI and wrote for his show. “Joe was able to extrapolate a universe from a single molecule and as such, his font of creativity never went dry.”

After several years in Washington, D.C., that included a brief stint hosting Weekend All Things Considered and producing for NPR Playhouse, Frank relocated to Southern California in 1986 and won a spot on KCRW.

Harry Shearer, whose Sunday-morning KCRW staple Le Show aired before Frank’s In the Dark, considers Frank the greatest radio artist of his era. Shearer, the voice behind many characters on The Simpsons, said part of Frank’s genius was his use of those baritone pipes.

That voice was like “a fist coming out of the radio,” Shearer said. The fist was enhanced by audio processing. In the days of analog recording, Frank would record his voice tracks with Dolby encoding and play them back in the mix without the Dolby on, effectively adding an equalization that was not tweaked with great care.

“He just knew how to use that particular instrument in the most effective possible way as an emotionally expressive and sardonically subversive presence in your head,” Shearer said. “It seems to me as a listener that the cult of public radio voices seems to be, ‘We want voices that just sound like a person talking to a friend in a room.’ But Joe sounded like a person who had come late in the night, perhaps unbidden, took a seat right next to you and would not let you get up. He had something very urgent and important to say to you, and that was the subtext of the way he approached using his voice on the radio.”

Among radio producers, Frank had a reputation as an obsessed perfectionist. In Carlson’s documentary, a KCRW engineer recalled times when a reel-to-reel tape had to be yanked from Frank’s hands to air in time. A volunteer at the station recalled seeing audio tape pile up around Frank’s feet in a production studio.

“We could be [working] in the studio 24 hours,” recalled Farley Ziegler, who served as a story editor and occasional performer on In the Dark at KCRW in the early 1990s. “It was always about getting the show right, not about the length of time it took to get the show right. I welcomed that particular work mode.”

“Joe worked with his actors in a highly improvisational way — he was always recording the riffing — but once he was in the studio to record the show, that was precision and super–fine-tuned orchestration of the piece,” Ziegler said.

KCRW’s former station manager, Ruth Seymour, deserves credit “for having the guts for putting [Frank] on the air and giving him a radio home,” Shearer said. But Seymour cut Frank’s show from KCRW’s lineup in 2002 after a 16-year run. When contacted for comment on Frank’s passing, Seymour said she had nothing to say.

Frank is survived by Michal Story, his wife of six years. After he died, she posted on Facebook, “No words will ever possibly capture the feeling of my shattered heart.”

Watch the trailer for Joe Frank: Somewhere Out There:

Thanks for this and the link to Hearing Voices too.

I wonder why KCRW’s former boss had “nothing to say” about Joe? I heard him do a monologue at Largo in LA where she waits at her door unwrapped in a robe — magenta, mebbe? — inviting him out of the dark…

(A Firesign Theater “flimsy burnoose!” comes to mind)

Or could be for some other reason.

Because she fired him for no good reason

yes, the story is pretty ugly.

Beautiful story!

He was a genius and because of that, I hired him at NPR to host Weekend ATC. But, it didn’t work because he simply could not restrain himself into the regularity and requirements of a network radio show. It was my mistake to try to “train” him or rein him in, as it would have been lobotomizing the genius and free spirit out of him. I still listen to his work in awe and wonder.