Andrea Seabrook of ‘Marketplace’ on the new poles of American politics

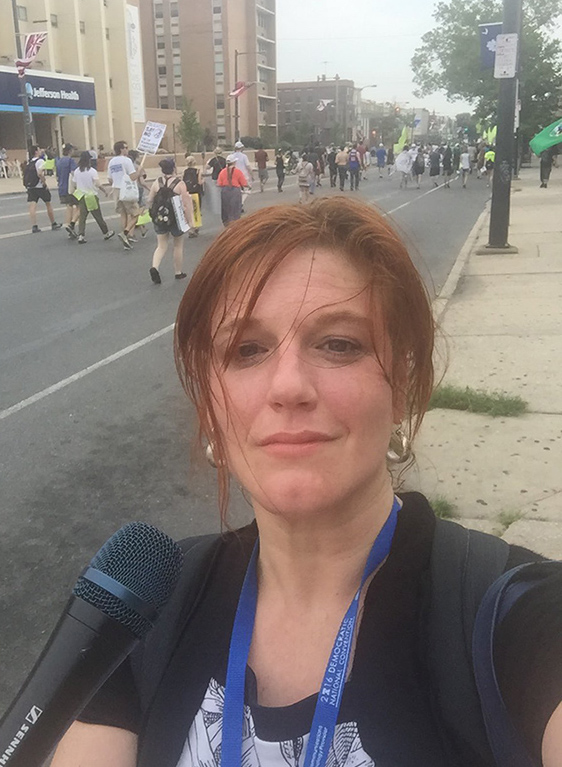

A sweaty Andrea Seabrook in a selfie taken outside the Democratic convention in Philadelphia

A couple years before all the cool kids started quitting NPR and launching podcasts, political reporter Andrea Seabrook quit NPR in 2012 and launched a podcast. She’s the OG of that particular trend. The show Seabrook created — DecodeDC — was a direct reaction to her dissatisfaction with the kind of political reporting that NPR demanded of her. Seabrook left DecodeDC last summer after a successful run, and now she’s come back to public radio as Marketplace’s new Washington bureau chief. In an interview on our podcast The Pub, host Adam Ragusea asked Seabrook how she’ll do public radio political coverage differently this time around. She spoke with him as she walked among protesters outside of the Democratic convention in Philadelphia.

Andrea Seabrook: It’s kind of a weird place to start the interview, but I’m walking down Broad Street in Philadelphia on my way from the Pennsylvania Convention Center to the Wells Fargo Center, which is where the Democratic convention is. And I’m kind in the front of a big Bernie Sanders march; it’s kind of Bernie Sanders and everything else.

I see signs that say, “Claim Your Democracy” and “Vote Jill Stein in 2016” and “Bernie for President” and “Bern It,” of course. Welcome to the Democratic convention, Adam.

Adam Ragusea, Current: Thank you very much, I’ll just jump right into it. Andrea, as someone who has many times spurned the way that political reporters cover politics as spectacle, as game, as sport rather than as substance, what the hell are you doing there?

Seabrook: It’s a good question. Part of me is like, “Yeah, everyone should be protesting on all sides. This is democracy.” Another part of me is like, “Do you realize how much you’re being used by the parties to let off steam?” It’s like almost like letting steam out of an old radiator, right? As long as the protesters on either side, on both sides, do whatever they’re quote unquote “supposed to do,” then I don’t know what progress any of us has made.

So, Adam, how much do you want this to be a personal interview about Andrea? Because you caught me in a moment of personal weirdness.

Current: If you’re in a moment of personal weirdness, then I’ve got you right where I want you.

Seabrook: Good journalist! Good journalist!

Current: Seriously, how are you feeling right now? What’s going on?

Seabrook: Here’s what I feel: My dad is a Republican, and my mom is a Democrat. They’re best friends and they’ve joked my whole life about going down to the polls and canceling out each other’s votes. They’ve tried to sneak around each other to see who can make the other forget that it’s Election Day, so that their vote will actually count because they know they counter it.

And I guess one of the driving factors in my coverage is that the polarization that we have assumed as Americans on either side is true. I honestly feel like we’ve been duped into feeling that we’re so very different from the people who live next door to us of the other party, whatever that may be, and the only people, the only groups that that serves is the party establishment. Now I’m not saying, “Go burn down the house” and all that stuff. I think there’s a rational and good place for parties in America. It’s just that to act as if, to believe that we’re that different from one another … my Uber driver down to the Democratic convention today came from Albania and was driven out because of the ethnic cleansing. He doesn’t care one whit who the president is. He’s in the best place in the world. He’s in the best country on earth. I don’t know, Adam, you got me in a place, man.

Current: I love having you in a place. By that logic, then, I would think that maybe you would be thrilled by the rise of Trumpism, considering the extent to which it scrambles traditional party allegiances.

Seabrook: It’s not just Trumpism. I am, in fact, thrilled by the scrambling. I endorse no party; in fact, I don’t vote, Adam.

Current: Seriously, you’re one of those?

Seabrook: Yeah, sorry. I know people think I’m crazy, but back in 2004, when I was covering both the Kerry and the Bush campaigns, there was a moment where I said to myself, “You know, if you’re going to have like a secret horse in the race, then you can’t cover it well.”

And so I said, “OK, well I won’t vote.” Whoever I decide might be the better candidate, I’m not going to vote for them; I’m not going to vote for anybody. And that freed me to see things that I couldn’t see before. I make no promise that this would help anyone else … but I do vote in my state and local elections. Elections I don’t cover I vote, but elections I cover I don’t vote in because it helps me see the realities of both sides.

Current: This is really interesting because if [NPR White House correspondent] Scott Horsley told me what you just told me — “I don’t vote in order to stay impartial in my soul, in addition to in my coverage” — that wouldn’t surprise me at all. I like Scott a lot — and he listens to the show, so I like him even more.

Seabrook: I love him, because he is a wonderful man.

Current: Sure, he’s a wonderful guy, but his approach to political coverage is pretty conventional; he’s a pretty straight-ahead reporter. Whereas you’re someone who has no hesitance about telling your audience what you think about a situation. You’ve really broken out of the traditional impartiality model, and yet you also don’t vote in order to stay impartial within your soul. It presents itself to me as a contradiction, although you’re about to explain to me why it’s not a contradiction.

Seabrook: You’re funny. Yeah, I hope that I can achieve what you have just said. I think that having covered Congress and the White House and politics for more than a decade, I feel like what I understand is that most Americans are in the middle of the bell curve. The people that I know and love are anywhere along that line, but most of them are in the middle. Most of them have values that uphold, I don’t know, “truth, justice and the American way,” Adam.

But most members of Congress, they may look like us, we may elect them, but the way the system is set up means that they’re opposite a bell curve. If you track the American electorate from left to right, they would be highly polarized on either end and there would be very few in the middle. So it’s like the opposite of a bell curve. It’s not very good radio, explaining a line, but the point is that while Congress, the Senate and the House appear as if they represent us, they actually have more or less an opposite stance than most Americans, meaning that they are way more polarized.

The answer to that is to refuse to believe that we are so very different from one another, I guess.

That’s not just like some liberal hippy-dippy or Christian hippy-dippy or whatever you want to call it; it’s not some crap. It’s informed by two decades of reporting that says that the people that I talk to — whether they’re in a diner in Iowa or here on the street in Philly or in a restaurant in Cleveland or even in Silicon Valley or San Francisco — we are so much more alike than we are different. And the only thing that it serves to believe that we are super-different are the ends of the parties themselves.

Current: Right. I’m thrilled that you as a journalist feel comfortable coming out and saying that because I think your opinion on that issue is earned. It matters what you think; it’s valuable. But why then would you stop yourself from voting for a presidential candidate who also recognized that truth? There’s a lot of people right now in my stupid internet world who are telling me that Gary Johnson is the candidate who represents and recognizes just that. Why would you stop yourself from voting for somebody who recognizes that truth?

Seabrook: Because, Adam, ultimately I don’t think the American electorate is split along the left or right poles. I believe those poles are over.

Current: I’ve heard like three different theories as to what the new polarity is; what is the new polarity?

Seabrook: The new polarity is inside-outside. It’s people who have access to government, it’s people who have access to wealth and power, and people who do not. That is the underpinning of all of the coverage that we have done on Marketplace. It is the underpinning of my understanding of the environment that we’re in. There’s a reason why Trump appeals to people who are in unions. Unions are a traditionally Democratic electorate, but Trump is coming out and saying, “The economy doesn’t work for you. The government doesn’t work for you.” That is what these people have been waiting to hear.

On the other side you have Bernie, Bernie Sanders, saying pretty much the same thing. And so you see that what actually drives people to one side or the other has more to do with the new poles of inside and out than it does the old ideas of left and right. And there is so much more … I mean, listen, Adam, the moment that you switch your viewpoint from left-right to inside-out, the Tea Party and the Occupy Wall Street movement are suddenly on the same side.

Current: Which is why I’m suspicious about this way of thinking that you are presenting. I know a lot of those people; they don’t have that much in common. … Culturally, they hate each other. There is some substantive difference between those two groups.

Seabrook: They have substantive differences about what they would do with the economy once they get it to a point where it is a fair playing field, but the ultimate basic tenet of both sides is that there should be a fair playing field. I’m sorry to be an asshole elitist philosopher about this, but I think many people on both sides of those particular movements don’t even understand how similar they are. If they could just say to themselves “We are going to fight for the fair playing field” and then engage in an incredible battle of the ages for what we believe after the fair playing field, then they would be on the same side.

Right? But it’s actually the left-right 20th-century old-school system that keeps them on different sides from the beginning.

Current: I don’t think it’s elitist for you to say that people participating in those movements don’t have the facts to know how similar they are. Our profession is predicated on the idea that people need facts and information that they lack.

Seabrook: And that we know stuff.

Current: OK. So this gets us to what you’re doing right now. You quit NPR in 2012, right?, and you did it kind of Cartman-style; it was a little “Screw you, guys, I’m going home.” You said, “The way that we have been doing political coverage at NPR — in fact, across the entire mainstream media — is fundamentally bankrupt. I’m going to go start my own podcast, or I’m going to do my own thing. I’m going to do it the way that it’s supposed to be done.” And you did DecodeDC for a bunch of years. You did it really, really well, a lot of really cool shows.

But now you’re back at Marketplace; you’ve come back to public radio; you’ve come back to a public radio show that is even more focused on daily grind-it-out coverage, arguably, than NPR was; you’ve come to a place where the stories are even shorter. So how are you going to do it differently this time? How are you going to not be part of the problem this time?

Seabrook: I can’t claim to not be part of the problem, being a journalist, but I will say that Marketplace is focused on the one thing that I think is the story, at least at the beginning of the 21st century, which is the income inequality. It is who the economy is serving and who it isn’t, and that’s not always an obvious sort of thing. I’m not saying, “Poor people are great and rich people are bad.” … I think we all understand that it’s much more nuanced than that. But one thing that I love about covering this for Marketplace is that we know there are insiders and outsiders, they know. We at Marketplace understand that, and we’re ready to say it, name it. I never wanted to rip apart NPR. I just couldn’t.

Current: You did it in a very diplomatic way.

Seabrook: Right, and the people there are amazing. I mean they’re amazing journalists — on the Washington desk particularly and all over. But the thing about Marketplace right now — and I think public radio in general; I think maybe NPR has to catch up to this — is that we have a point of view. It does not mean you’re biased to have a point of view.

And I think it is just plain and simple fact to say that the economy serves some but not all; the government serves some but not all. And it has taken maybe a couple of decades, maybe more, for Americans, voters to recognize where they are in that strata. If that’s biased or anti-patriotic, then so be it.

Current: Let’s talk about like the specific kinds of coverage you’re doing. How long have you been on the payroll for Marketplace, like a week or two, right?

Seabrook: By my count I think I’ve gotten two paychecks. Three, four weeks maybe.

Current: So right now, when I search your name at Marketplace.org, I actually don’t see any traditional pieces of radio coverage yet. I don’t even know if you’ve done a Marketplace spot yet. What I see is this pop-up podcast that you’ve been doing. Do you want to describe what that is? …

Seabrook: I came to Marketplace not too long ago. Marketplace is an amazing program. I love all the people. I think people who are listening to this podcast know Kai [Ryssdal], and they know Lizzie [O’Leary] and Molly [Wood] and Ben [Johnson] and David Brancaccio; they know the whole gang, right? These are people who within the public media rubric have had to stay lean and scrappy their entire careers. They do more with less than anyone, I promise you, in the public media system.

Current: I think some of the people you just mentioned have rather generous salaries by normal American standards; I’m just going to point that out.

Seabrook: OK, I agree with you. Compare them to everyone else in the public media world, and the size of their staff, and what they do, how many minutes they put on per day or per week. … [E]ntering that kind of ecosystem is at once ridiculously difficult because you’re entering like a really startup entrepreneurial crazy culture. And, on the other hand, it’s ridiculously fun and crazy because you’re entering a startup entrepreneurial culture. I came in and I said, “I think we should cover the elections this way, and … here is what the new poles in American politics are.” All I have gotten is yes yes yes yes yes. There has never been a focus group; there has never been a top-down; there has never been a layer of bureaucracy between me and the coverage that I believe in.

I hate to be like a total … I’m not drinking the Kool-Aid here, man, I’ve been in enough places to know that it doesn’t have to be this way, and it’s been incredible. It’s been great.

Current: So how has that new freedom manifested itself? Tell us about the work that you’ve been doing from the convention so far and maybe we’ll throw to a clip.

Seabrook: We’ve gone to the Republican convention. We have done elements for every episode of Marketplace in the afternoon and Morning Report every day of the Republican convention last week and this week. We have been putting out a podcast every day, talking about what we see, what we find, the best tape we find called Politics Inside Out from Marketplace. And we have given an element to the stations. We decided from the beginning that we would give a 60-second cue and a three-and-a-half-minute feature to the stations every single day that the stations can drop into their coverage wherever they want. It doesn’t have to be on some silly timeline or someplace in their coverage.

That’s an incredible amount of content that we have generated and, frankly, at the Republican convention we had two reporters — me and Nancy Marshall-Genzer — and we had two producers in L.A., and that’s it. I don’t want to do this, but NPR had 45 people in Cleveland. They have 45 people here in Philly, and they’re trying…

Current: If you don’t want to slag off on NPR, I will. I think that’s excessive for two reasons. One, I just think that there’s too much division of labor at NPR, and reporters should be mixing their own damn stories. And, two, I just don’t think the convention is that big of a story. Do you?

Seabrook: No, I don’t think so.

Current: Then why are you there?

Seabrook: Because it is a story, and it isn’t the story, but it is a story. And particularly I think it is a story — not like, “Oh, here’s the convention. Let us tell you what happened here or what is happening here.” I can’t think of anything more boring than that. To me it is a story because of exactly what we’ve been talking about: the redefinition of the poles of American politics. This pair of conventions particularly is the best example I could give for how American politics does not actually separate along the lines the parties would have you believe. You have splits in both the left and the right.

I talked to a guy today, super Barney supporter, anti-trade, will not vote for Hillary, may or may not vote for Trump. But not voting, in some ways, is like you giving a vote to someone else — on both sides.

If there was ever any doubt, Adam, that American politics is not left-right, it’s inside-outside, these nominating conventions should sew that up for anyone listening.

Current: So we come now to the podcast that you’ve been doing from the conventions, Politics Inside Out. Is this going to be a continuous project, or is this just a single-serving, short-run series that you’re doing during the convention?

Seabrook: Frankly we launched this with no plans, as a complete and total, like, let’s do this, let’s just do it. We didn’t think about the future. We didn’t decide what we were going to do next.

We just said, “Let’s talk about this insider-outsider story, this narrative, from both conventions every single day of each campaign, each convention, and then let’s see what happens.” And, frankly, we’re waiting to see if it catches fire, if people are interested enough in the redefinition of American politics and the way we’re talking about it for us to do it even weekly. We’re trying to figure out what works.

Current: What’s on your coverage agenda? First of all, you’re not just a reporter anymore; you’re the Washington bureau chief. What’s next? What do you want to tackle once you get past the spectacle that is the place where you are right now?

Seabrook: The conventions here are the kickoff of what I want to do. I want Marketplace, I want public radio, I want America — just to be magnanimous — to redefine our politics in a way that actually makes sense instead of the bill of goods we’ve been sold about who is on whose side. I feel, like many Americans, the way we have defined our politics certainly for the last decade if not more has pitted neighbor against neighbor, going back to my mom and dad. Maybe I’m just a freak, Adam, but I don’t believe we’re that far apart.

In the same way that I feel like public radio, and Marketplace in particular, is not biased one way or the other, we have been painted with that brush to someone’s ends, to some group’s ends, to some group’s benefit. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to do that for us, I don’t want to do it in America, I don’t want to do it for any of us. The reason why so few people vote anymore — and you’re great if you get a 30 percent turnout — is because they feel as if their vote doesn’t matter. And to some extent they’re right. Their vote only matters on Election Day, and then the establishment gets in — and the people who are in largely work for the insiders, the people who already have access to power. That doesn’t mean that I’m allied to the Communist Party or something; it just means that there’s a new way to look at politics in America, and we don’t have to go for the old myths. And that is what I hope our coverage can accomplish.

Current: It sounds fuckin’ righteous to me. Forgive me, I had my doubts about your ability, anybody’s ability, to do coverage that’s going to sound and be that substantively different within the practical constraints that you have at Marketplace, where you have to jam out a show every single day with a very small staff, and you’re working in a really, really tight clock. How much can you really deviate from the norm when your standard story length is 90 seconds to two minutes?

Seabrook: Adam, I completely agree with you; I have my doubts as well. It’s more than a fair question. But I will tell you that the thing I have learned from the different groups I’ve been in — from a network to independent to quasi- to whatever I am now — in some ways it’s easier to work with a skeleton staff when you have an idea like this that is really, I hope, a game-changer than it is to work within a larger system, frankly.

Seabrook is 100% correct and Donald Trump knows it well. As an old political pro who served as Political Director for the RNC and as a consultant to campaigns for two Presidents, I assure you that this realignment will be greater than Nixon’s “Southern Strategy”. Compare the stock market gains to wage gains during the Obama years and you see immediately that respective roles of the two parties have been reversed. Clinton and Obama clearly represent the Elite Establishment. Four more years of their rule and the rich will truly be richer.