NPR founding programmer Bill Siemering on his days before joining the network

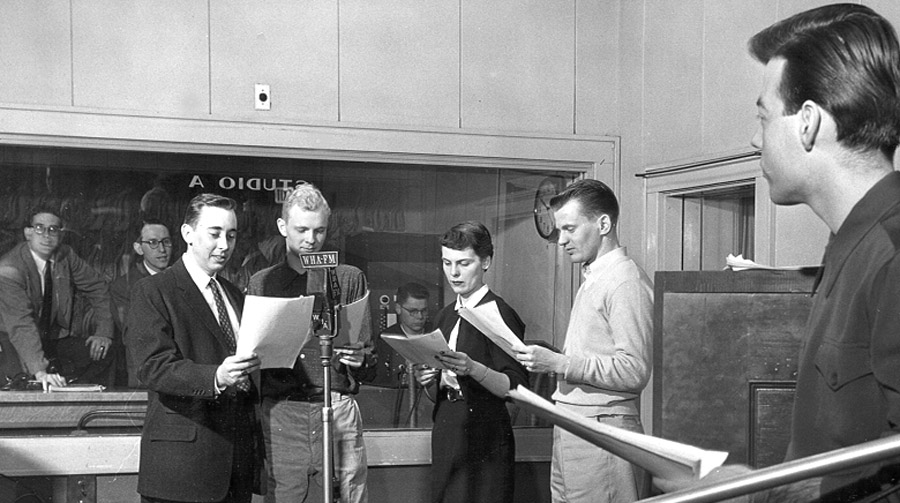

Siemering acting in a radio play at WHA, c. 1955–56.

Bill Siemering is perhaps best known as the founding program director of NPR and the author of its Walt Whitman–esque mission statement, still a source of inspiration for public media today. But Siemering’s career in public radio and community media extends well beyond his time at NPR. He discussed the arc of his career in an April interview on WFIU in Bloomington, Ind., with Adam Ragusea, host of Current’s podcast The Pub. In this first of two parts, Siemering begins by describing his introduction to radio.

Siemering: My first contact with radio in a meaningful way was going to a two-room country school outside of Madison, Wisconsin, and listening to the Wisconsin School of the Air twice a day. So the teachers would have a manual and prepare you for the class, that might be science, social studies, nature studies, music, art — all those things were taught by radio, by so-called “master teachers,” if you will. And so I learned from first grade on that radio was a source of information, education, entertainment and imagination.

Adam Ragusea: Were you thinking about radio as a career at that point?

Siemering: [laughs] In first grade, no, I wasn’t. But we moved into the city, and I went to a good high school and was active in speech work and stage crew and acting in plays and things like that. And as it happened, the speech teacher and my mentor at that time was married to the head of WHA, the Wisconsin public radio network. His name was Earl McCarty.

Ragusea: Arguably the oldest radio station in the country, right?

Siemering: That’s right. So when I graduated, [they said], why don’t you go down and see about working at the station? So I did. And I was going to work in doing scene designing for television or something, and he said, “We don’t have that going now much, so why don’t you work in radio as an engineer?” And that’s where I started.

Ragusea: What did your folks do for a living? What did they want you to do?

Siemering: My parents had been actors in the Chautauqua circuit. [They] put on plays in the Midwest, going town to town where there were very limited cultural resources. And one night they might have a lecture or a travelogue or something like that, and the last night would be the play. My father did a monologue in the afternoon. That was all before I was born. And my father was working at that time as a civil servant. He was the veterans’ employment representative for the state of Wisconsin, that is, he was getting jobs for veterans. He was a veteran of World War I himself.

Ragusea: So certainly performance is in your background, in your blood. You get into radio in Wisconsin, it eventually leads you to a radio job in Buffalo, New York. And that’s the one that I think gets you to NPR, so tell us about your time in Buffalo.

Siemering: So I went to Buffalo from Madison, and the station WBFO was really a student club at that time. And they were off the air in the summers. They didn’t go on the air till five in the afternoon and would go off the air for vacations, so it wasn’t a proper, serious station as we think of today. So we tried to upgrade that so it was a proper station.

I did a porch-to-porch survey in the heart of the black community to find out what their interests were, because they were not served at all, I felt. There were no people of color on television or in newspapers writing or in radio except on the white-owned, black-oriented music stations. And so out of that came eventually setting up a studio in the heart of the black community. And essentially all the programming from the weekend, from Friday through Sunday, came from that facility. Twenty-seven hours a week. This was really giving a voice to people that had not had a voice. We had a wonderful black arts festival one time with people bringing in their paintings, their photographs, poetry, we had live jazz and things like that, so it was really a celebration as well as talking about issues of concern to them.

Ragusea: What did they think about you, the white kid from Wisconsin?

Siemering: [laughs] Well, with some suspicion at first. I had to kind of prove that I was sincere, that I wasn’t Whitey that was there to try to rip them off or something.

Ragusea: So is it your work there, your really pioneering work there in Buffalo, that got the attention of the people who were putting NPR together at the time?

Siemering: Yes, and I had written an article for one of the educational media publications about what does it mean, going from educational to public radio. What are the ingredients that have to go into this new mix?

So part of that, I made quite a strong case there, stronger than in this mission statement, about the need for giving voice to minorities or people of color, as we say now. Because you know, Martin Luther King had said that we have to write our essays on the street. I would go to an advocacy organization called Build started by Saul Alinsky. And they would have a prepared statement about education and some issue with the schools. And the television would film this, and then they’d turn off their cameras and they’d say, well you know, we can only use 45 seconds of this, so do you want to do that again? And I thought, you know, these problems have been in the works — the history of this is three hundred years, it might take three minutes to explain this one issue. So that’s really part of the thing that prompted me to try to give a voice to people.

Ragusea: So it’s the late ’60s. You’re working in Buffalo, you’re in your early 30s, right? Broadly speaking, in what social category would you place yourself? Were you a hippie?

Siemering: I wasn’t a hippie, I wasn’t doing drugs or smoking marijuana or anything. But I did have a beard, which gave me the impression of maybe being a hippie or identifying certainly with cultural change.

Ragusea: So you fell in with the people who were putting the very nascent NPR together. How specifically did that happen? Did they call you, you call them?

Siemering: NPR, in its formative stage, had to have an election of the board of directors, and they did this by dividing the country up regionally. And I was elected from that, from representing the Northeast to the initial board of directors. And I think because I had written these articles and so on about the future of public radio, they asked me to write the mission statement. And my work in Buffalo was known also. I used the station in Buffalo really as a lab to experiment with a lot of different things. It was quite a creative place because there are a lot of creative writers there. And they had creative associates in music. So there was a lot of cultural excitement going on there, and I was reflecting that as well as the conflicts with the city or the issues going on in the city. So anyway, out of all that, I think they thought, well, maybe I could put something together for a mission statement. …

Ragusea: And then you got hired on.

Siemering: Right. I was hired to implement the goals. As you were saying, they were kind of lofty. And now you have to make it real, you know, which is the fun part and the challenge, you know. Talk is cheap.

Ragusea: But your job was director of programming?

Siemering: Yes.

Ragusea: The first program director for NPR, this is 1970, 1971.

Siemering: Right. I was hired and I started work in November of 1970. And All Things Considered started May 3, 1971.

Ragusea: What was NPR physically at that time?

Siemering: Well, in the very beginning we had no studio. [laughs] But then we did build a studio, but it really wasn’t fully equipped and operational properly to do mock-ups of the program until a month or less before we went on air.

Ragusea: But what did it feel like? Was it a dumpy one-room kind of thing?

Siemering: It was in an office building right in the Farragut Square area in Washington, D.C., if people are familiar with that, not far from the White House. … It was just kind of a drab office building. And we had a few rooms on a floor there.

Ragusea: Compare yourself to your other colleagues at the time. Were you a little bit older at that point than the folks in the halls?

Siemering: I was younger than my colleagues on the executive level, and maybe a little older than the lot of people we hired.

Ragusea: You did a lot of the hiring yourself. Who did you hire?

Siemering: Linda Wertheimer. Ira Flatow. Susan Stamberg. Some of those that are still at NPR.

Ragusea: That’s a pretty good batting average.

Siemering: Jonathan Baer, who’s a wonderful associate producer still there. So those are people that people recognize as names of people I hired.

Ragusea: Where did you find them?

Siemering: That’s a good question. [laughs] They came in, they heard what was going on. I hired some people from Buffalo. Ira had been a student at Buffalo. Mike Waters was one of the first hosts of All Things Considered, co-hosting with Susan Stamberg, came from Buffalo and WBFO. Jeff Rosenberg worked at the American Red Cross. Our news director was Cleve Mathews, who was a newspaper person initially from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and he was a Washington editor for The New York Times. And I hired Robert Conley, who had worked at NBC television and also at The New York Times. Because I really felt we really needed to have solid journalists. And at that time they weren’t in public radio or even in commercial radio that much, I don’t think. Because we needed a strong editorial direction, you know, people that could evaluate stories, make sure that all the bases were covered, that it was fair and properly presented.

Ragusea: And in fact, this was a point of contention with some of your colleagues in the executive ranks of the nascent NPR at that time. They sort of said, why don’t you hire radio people who know radio?

Siemering: In one of the histories that’s been written about NPR, they said that my colleagues on the executive level had disdain for me when they saw who I had been hiring, because I thought that anyone could learn radio because I had worked in the ghetto and with students. And it’s true, anyone can learn radio. The mechanics of it are quite simple. But what you can’t teach as easily, certainly, is curiosity, and empathy, and being a good listener, which is the key to good interviewing of course.

So some people I hired didn’t have any radio experience. A very few were doing any on-air work. Everyone that did on-air, I was very careful about how they sounded on air. Radio is a sound medium, and I pay a lot of attention to that. When I’m hiring people, I will listen to their sample tape before I read their resume, because the listeners don’t have the resume. I don’t want to be influenced by a degree from Harvard or something. It’s how you sound on the air that’s important, your air presence. Not every reporter makes a good host.

Ragusea: Indeed. … You launched All Things Considered in 1971. … You didn’t have the studios to really create what we would call a pilot or a mock-up of the program that you could send out to the ninety stations around the country that had agreed to air the show to give them a sense of what they were going to get, so instead you wrote them a memo. And it’s another wonderful document. I wonder if you could read from this memo, this vision for what All Things Considered would be.

Siemering: Yes, I wanted to give them some idea, because I think that they were getting restless. What is this thing going to be like coming down the line? And one of the problems was, frankly, that this was the first time that that the public stations were connected by a live interconnection. And so … I think some of them had in mind that it would sound like NBC or CBS. It wasn’t going to sound like that, because why would we duplicate what’s already on air? So it would have to have a different sound. More natural. Conversational style. Using sound to help tell the stories, getting out of the studio. Using music. And being inclusive. Not only of what’s going on in Congress … but really dealing with a culture that is where the new comes from. I just wanted to kind of assure them that what we were doing was, there was a rationale behind it. And so I told them a little about the staff and that we wanted to have diversity of ideas, and there were people that had a lot of good knowledge about the arts that may not have had broadcast experience, but that was OK. And assure them that the editorial, the journalism was going to be solid.

And there were some core values I also talked about. I said that it would have a unity of events, ideas natural to the unique characteristics of the medium, growing out of the need to present a reality which is believable to all segments of the total population. People will be valued and treated with respect and positive regard and not as adversaries by the program staff. The listener will have a sense of reality of authentic people sharing the human experience with emotional openness. Each unit will be related to the whole with the form following function. Division of time growing out of content rather than the arbitrary walls evenly spaced between units. Not all that has come true, of course.

Ragusea: Indeed. All Things Considered, for those listeners who don’t know, and Morning Edition do not proceed with an open format anymore. If you were to look at the program clock, we call it, the schedule by which every hour of the show proceeds, it really looks like a dartboard. Every minute is rigorously scheduled in a standardized format, and it’s something that is necessitated by the logistics of uniting a national network in Washington with hundreds of local public radio stations around the country that all have their own content that they need to interlace into what you’re doing nationally. But you were starting there from a very idealistic place, which is saying, let’s simply let the content take the space and the time that it needs. Let’s not impose anything artificial on it. And that’s a very lovely idea even if it couldn’t come true.

Siemering: Well, people are doing that now on podcasts. So there’s a place for that now.

I want to just emphasize a couple things there. People will be valued and treated with respect and not as adversaries by the program staff. And that was also within the staff itself. We wanted to have that civility, positive regard. It’s not meaning that you don’t call [out] a politician or a source when they’re not answering a question or telling the truth, but that the basic assumption is that you’re respectful of that person. When you start attacking, you just get a defense, and you don’t get to the real person. Because then you’re not going to really go very far if they feel they have to be defensive.

Ragusea: Was that value a notable contrast with the media of the time? Certainly broadcast media today can be extraordinarily contentious and poisonous and all kinds of yelling and shouting. In 1970 — I was born in the ’80s, so I maybe have a rather idealized impression, but my sense is that broadcast media was more civil back then.

Siemering: I think Mike Wallace was on the air then, on radio, and there were other talk programs that were pretty argumentative, you know. Protestors were sometimes called “peaceniks” or that kind of thing, stereotyping people. So that was what was behind that.

And that it should be authentic. It shouldn’t sound artificial. Because I think that’s something that people are hungering for now, is a sense of authenticity. Now. There’s a phoniness — I think you hear this more on television sometimes — but it’s kind of playing almost a character sometimes. We did have one cutaway in the program, I think it was around 53 minutes in, where I wanted to lift the curtain and be transparent about what we were doing. So Cleve Mathews, the news director, talked with the reporters on the news staff about the stories they were covering and what they were going to cover, to talk about the process of putting the program together if you will. And I still believe that that’s an important thing that people are very interested in. Serial, for example, the podcast that was so popular, part of that was because Sarah Koenig was taking you behind the scenes saying, “This is what I found, and then I went here and discovered this, and so the story turned this way.” It’s a process that’s as important as the product sometimes.

Ragusea: Yeah. I like to say that authenticity is the new authority. Authority is an artifice. But with authenticity, you can gain people’s trust by showing them how you have done what you have done, how you have come to your conclusions, and NPR under your leadership was a pioneer in that entire concept.

… [All Things Considered] certainly had its ups and downs, I imagine, but it won a Peabody in its second year. You must have been feeling pretty good. And then something rather unfathomable happened. NPR fired you. How did it happen?

Siemering: Well, I had a meeting with the boss, President Don Quayle, who had hired me in March or so. And he had some issues he wanted me to address, and I addressed them, I thought.

Ragusea: What kind of issues?

Siemering: I think it was more administrative kind of things and some stylistic things.

Ragusea: What do you mean? You said that you were a guy with a beard. Were you insufficiently formal for the straitlaced world of broadcast news?

Siemering: Yeah, I mean, some of my colleagues had said “Somebody should tell Bill this isn’t the Third World or something.” I mean, I wasn’t that far out, but I did come from this university setting that was very progressive. And they were, some working in New York and in corporate offices. And so there was that kind of clash, perhaps, of the way of looking at the world. … And I’m certainly willing to admit that it was evidently not a good fit for me. I wasn’t doing what they wanted.

So one Sunday morning Don called me into the office — it was December 10, actually — and said, I think it’s time for you to leave. And I said, well, I thought I had addressed all the issues that you raised. And he said, yes, you have, but it’s too late. So I was really quite crestfallen. I should have seen it coming, I guess. I should have been more sensitive to that, or whatever. Anyway.

So from there I went out to Minnesota Public Radio. Almost like an exile [laughs] … It’s probably very much like Siberia in the winter. And I started working there as a manager and producer/reporter and had great fun. Bill Kling, who was president of Minnesota Public Radio, said just go out and get the station qualified and put your feet up and think. And it was a wonderful invitation.

I didn’t put my feet up, but we did create some new programs that were fun. One of the series we did with John Ydstie, who is at NPR, you hear him doing economic reporting. He was a student, and as he graduated he did — we had a chapel broadcast from Concordia College. So I got a grant to do sound portraits of six small towns in North Dakota. I think there were 26 half-hours altogether. And I’d also set a goal for us to contribute to NPR. Because part of the plan I had was that the stations would not only be used to distribute the program but as a source of information so the country could hear itself. And I thought if you could do it from Morehead, Minnesota, you could do it from anywhere. And we did get 52 pieces on NPR programs … So we met that goal.

Ragusea: Certainly. And now Minnesota Public Radio is one of the most important public radio stations in the country, right up there with the big-city stations in places like New York and Los Angeles, and no doubt part of that is your legacy. Now Bill, it was at this time when you were out in the gulag in northern Minnesota that you actually kind of dip your toe back into the world of National Public Radio. What happened?

Siemering: Well, I did appreciate the opportunity to have the freedom that you have. Again, it was a little like Buffalo. I had a lot of freedom to do some experimental programming, if you will, or to to imagine different things. And so I really enjoyed that I was working with Marcia Alvar. It was her first real job in radio. She had been working in an unheated co-op garage in Minneapolis. I think she wanted to come in out of the cold. Marcia went on to become the executive director of the Public Radio Program Directors, as you know. We created a program there called Home for the Weekend. It was fun. I did a program called The Arts Around Us. And we were doing reporting on migrant workers and farming and things like that. I worked on farms sometimes on the weekends and so on.

Anyway, I thought my career was pretty much over when I went out there. I didn’t see where I was going from there, really, and I didn’t worry too much about the future, but I did feel that somehow I had to kind of test where I fit in the system. And so I did run for being on the NPR board of directors again. And I wasn’t on the kind of “approved” list, but you can be a petition candidate, kind of like a write-in. So I did that, and I was elected to the board. So that kind of helped me recover a little bit of my self-esteem to at least have the acknowledgement of enough station managers that I thought I could still contribute something to the system.

Ragusea: But then you step in and you’re a member of the board. The board is above the boss. You were the boss of the people who had fired you.

Siemering: Well, the man that hired me, Don Quayle, had left by that time. So I wasn’t supervising him.

Ragusea: That would’ve been fun. So what was your role on the board at the time. Were you kind of a gadfly?

Siemering: No, I was on the board quite often actually, in that I was elected the board for a three-year term, and then I think you could be maybe elected again, I’m not sure. But then sometimes I was brought back to fill an unexpired term. Like when there was a financial crisis, when Frank Mankiewicz was the president, I was asked to come back on the board.

Ragusea: That’s in the ’80s, right?

Siemering: So I served a lot, off and on, maybe a total of ten years or something like that. I was chairman of the program committee once. I was secretary once. One board chairman explicitly did not want me on the program committee because he thought I would favor them too much. So I was on the membership committee or something like that.

Ragusea: And one of the things that listeners might not understand about the way that public radio works — you sort of might imagine that maybe NPR is the mothership and that all of the stations are its children. But it’s really quite the opposite. The stations actually have a controlling majority representation on NPR’s board. NPR actually works for the stations in effect. And that must have been an interesting dynamic to be a part of.

Siemering: And that’s one of the things that differentiates us from the BBC, for example, or the large state public broadcasters in the world. And I think it’s an excellent model, really, because it forces the local stations to excel. As I was saying, you’ve got to have programming that is distinctively different, and also so meaningful that you’ll voluntarily give money to it, and the network program has to be that good or the stations aren’t going to pay the fees to pay for it. So it puts everyone up for evaluation, if you will.

Related stories from Current:

“He got his start in radio at one of the country’s oldest educational stations.”

Surprised nobody’s noticed this: WHA, Madison is not one of the oldest. It is THE oldest educational station and arguably the oldest radio station.

In writing that introduction, I deferred to Wisconsin Public Radio’s own history, which says, “On Jan. 13 [1922], 9XM is relicensed by the US Commerce Department as WHA making it one of the oldest radio stations in the United States, and one of the first educational institutions (along with WLB at the University of Minnesota) to be granted a license in the new “limited commercial” category for broadcasting.” http://www.wpr.org/wprs-tradition-innovation

There’s considerable debate over that. More than a few radio historians say the now-defunct 1XE in Medford Massachusetts was the first. But it kinda depends on what you mean by “first”, too. First to broadcast continuously? What’s “continuously”? Do you give allowances for NABET…or WWII…when the gov’t radically revamped the broadcast dial and forced many stations off the air, temporarily or permanently? Or maybe you say it was first to broadcast voice? (instead of morse code) Lots of different ways to define it.

If you haven’t already, I recommend talking to Donna Halper at Emerson College. She’s a real genius at radio history and invariably a hoot to chat with.

Oh, and one thing that anyone with even the slightest knowledge CAN agree on is that KDKA is by no means the “first” radio station at ANYTHING. That was always pure marketing, nothing more. :)