How NPR One data points to new ways of thinking about local content

It doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to leave a job at a local station to take a job at NPR because you care about local news. But that is exactly what I did nine months ago.

It doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to leave a job at a local station to take a job at NPR because you care about local news. But that is exactly what I did nine months ago.

It troubled me to see big digital-news sites such as Vox and digital radio pure-plays like Spotify gain audience without having any place for local news. This was particularly distressing as I sat in Michigan watching state-appointed emergency managers take over city after city from elected officials, seeing our infrastructure literally collapse and witnessing the start of the Flint water crisis months and months before the national media took notice. These were major stories that simply would not have been told had it not been for local news outlets, including public radio stations.

If local news is going to be there for the next generation of listeners and readers, someone has to figure out how the emerging digital platforms can provide local news. This vacuum is what sets NPR One apart from other news apps. It has been designed as a partnership with stations so that local news is part of the user experience. Granted, we have more work to do to improve how local news is curated and presented in NPR One. But already there’s a lot we can learn from NPR One data that can help make all of our local efforts better.

If you aren’t familiar with NPR One, it is a digital listening platform that mixes national and local public radio stories with podcasts from public radio and beyond. It gives listeners the on-demand, personalized experience that they’ve learned to expect from services such as Pandora and Netflix. When someone listens to NPR One, the flow of stories starts with national and local newscasts. Then they hear a selection of stories from NPR’s newsmagazines and their local station. NPR One also allows users to explore and search for podcasts and stories from a variety of producers.

When you program a radio station, you get high-level data from Nielsen about the average number of people listening to quarter-hours or dayparts. But in NPR One, we get moment-by-moment information about how listeners are using newscasts, stories and podcasts. It is information that tells us a lot about the local that works.

Local newscasts that work

For years I’ve sat at programming and news conferences listening to people argue about whether stations should bother with local newscasts. Focus groups and surveys suggested listeners didn’t value local newscasts, so a common recommendation was to redirect local efforts to in-depth feature reporting and leave newscasts to local commercial radio counterparts.

NPR One data tells a different story. Local newscasts, and national newscasts, are the least skipped type of content we present. When a listener hears a local newscast, statistically they are more likely to listen to NPR One again and listen longer than listeners who don’t get a local newscast.

So why is the NPR One data showing something different from what earlier research turned up? You could write it off as a difference between NPR One and radio, but hang on. There is another possibility. We are seeing the differences between what people say they like to listen to and what they actually listen to in NPR One. For instance, we are more successful at getting you to listen to more episodes of a podcast we’ve observed you to have listened, liked or shared than at getting you to listen to episodes of a podcast you’ve followed.

Apparently, what we say we like differs from what we actually like enough to listen to.

That makes me wonder if newscasts are like the bread on the table at a restaurant. You probably don’t choose a restaurant because of that bread, but you’d be disappointed if it weren’t there. Newscasts might be a utility, something you wouldn’t rave about excitedly in a focus group, but they are something you expect to be there. You listen to them and rely on them to give you a roundup of the news in your community.

That said, some newscasts perform better than others. NPR’s Innovation Accountant Nick DePrey and I analyzed local newscast performance in NPR One and found the following:

Length matters. There is a sharp drop off in newscast listening when a cast exceeds five minutes. Two minutes long works as well as four, but once you get to five minutes you have hit a cliff. This means you don’t have to create big, long complicated newscasts to give listeners the information they are seeking about the headlines in their community.

Hosting matters. Newscasts with a strong host presence performed better than ones with weaker, more tentative hosts. All of the elements of great hosting appear to give a newscast a leg up.

Newscasts should have multiple stories in them. Local feature reports placed in the newscast slot at the beginning of the NPR One flow didn’t perform as well as a traditional multiple-story newscast.

The takeaway here is that a local newscast works best when it gives listeners a well-presented roundup of the most important news about their community over the course of just a few minutes.

Local features that work

Newscasts may serve listeners by summarizing what has happened in their communities. But listeners turn to local features when they want to go deep and find meaning and understanding.

I spent three months analyzing NPR One data for all the local segmented content (features and interviews shorter than 12 minutes) that had over 300 listens. I examined the stories that performed best as measured by what we call a “love rating,” which looks at the stories that are shared or marked as interesting. What I found looked familiar.

In 2011, two trainers at NPR identified the nine types of local web stories with the highest levels of engagement. The types included stories that were “Place Explainers,” “News Explainers” and “Crowd Pleasers.”

The NPR One audio stories that rose to the top were strikingly similar to the “9 types” of web stories:

- Stories that follow the Hearken approach of answering interesting local questions (e.g. “Why Is There Such a Large Ethiopian Population in the Washington Region?”)

- Stories that tap a sense of local pride (e.g. “How Flying Dolphins Kept This Old-School Kansas City Hardware Store Alive”)

- Stories that make sense of a big local issue or controversy (e.g. “PayPal Move Makes Economic Impact Of HB2 Real”)

- Stories that had a “gee whiz” quality about them (e.g. “That Time UT-Austin Waged a War on Grackles”)

- Topical buzzers about that thing everyone is talking about (e.g. “Texas Education Board Candidate Who Called Obama a Gay Prostitute Won’t Back Down”)

By contrast, the low-performing local feature stories in NPR One were very different. They called to mind another story classification created by Jay Kernis, a former NPR senior v.p. of programming.

In 2009, Kernis mapped out four different “tiers” of news coverage:

- Tier One — Commercial: “If it bleeds, it leads”

- Tier Two — Staged: News conferences, meetings and announcements

- Tier Three — Local impact/national: The local impact — or local representation — of a national or international story

- Tier Four — Local meaning: Events, people, trends or ideas that make a real difference to a community

The stories that didn’t perform well in NPR One were Tier 2–style stories. These are reports on meetings, political and judicial pronouncements and news conferences. In general, they tended to be stories where, frankly, there wasn’t much news. (There were very few Tier One stories.)

The stories that did well in this analysis were what Kernis describes in Tier 4 — those stories about things that make a lasting difference in a community, as well as those that examine overlooked trends and events.

So the data shows feature stories work best when they go beyond just reporting what happened. They provide context, meaning and relevance to the people in your unique community.

A thing that just works

Before we get to podcasts, let’s step back and talk about something that just seems to work regardless of whether we are looking at local or national content.

The content that does well in NPR One starts strong. It grabs listeners with a big idea or something intriguing that they care about.

In an analysis of feature-report ledes that former NPR One Managing Director Sara Sarasohn conducted, she found that the stories that performed best had short host introductions (less than 22 seconds) and began with a big, grabby idea. The top-performing introductions didn’t actually start with a news peg or even lead with the most recent information on the story. Instead, they started with a statement that piqued listeners’ interest or made them understand what is at stake. We as journalists have always valued reporting the latest information, but this analysis suggests that a listener doesn’t care about what just happened until they care about the subject at hand.

Story ledes that underperformed were ones that were about us! They were self-referential and often started by telling the audience about our series or a report we did yesterday. These were ledes that started with phrases such as “In the second of our three-part series …” or “Last week NPR reported …”

Other underperforming introductions started talking about one thing, but the last line of the introduction (and the story itself) pivoted to reveal the story is about something else. Often this “bait and switch” was done to incorporate some sort of time peg to a story that isn’t really timely.

We saw a similar thing when we looked at podcasts. When we play podcasts for listeners in NPR One, the ones that perform best start strong. Podcasts that start by introducing a guest’s credentials get more skips than those in which the actual story starts at the first second of the podcast.

NPR trainer Allison McAdams summed it up perfectly in a blog post she wrote about the start of stories: “If your story or podcast episode doesn’t promise something interesting at the beginning, fewer people will listen. The same goes for a three-minute story or an hour-long story. For listeners, there is simply too much audio to choose from, so we have to compete fiercely for ears. We have to grab the audience and make them want to stick around.”

Local (and national) podcasts that work

There are some general findings about what makes one podcast more successful than another, regardless of whether they are national or local in scope. We can’t overstate how important the start of a podcast is. When Nick DePrey examined podcast-listening data on NPR One, he found a typical episode loses 20 to 35 percent of the listening audience within the first five minutes. The rate of the dropoff is higher within the first five minutes than at any time until the credits roll.

What does this tell us? Listeners make their decisions to commit to a podcast in those crucial opening moments. A mediocre episode with a good intro will almost always perform better than a great episode with a poor intro. In a world in which we’re increasingly competing for the listener’s attention against so many other entertainment options — audio or otherwise — you need to justify from the very first moment why the audience should choose you. Only established shows with loyal followings can overcome uninteresting or non-engaging beginnings.

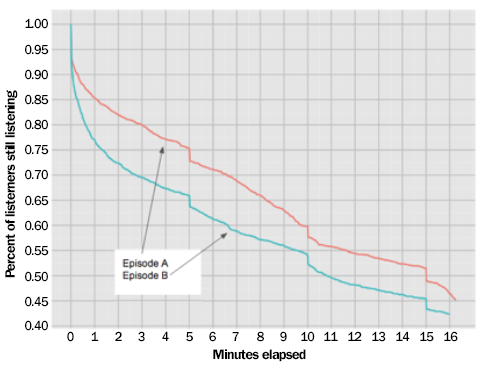

This retention graph compares how listeners responded to two different episodes of a science podcast, showing the percentage who stuck with the program at each minute elapsed. The episode with a stronger intro, displayed in orange, held listeners better in the first five minutes; the episode displayed in green had a sharp drop in listeners within the first minute and never made up the difference. This trajectory is very typical for all podcasts. The episode with the stronger intro almost always keeps the audience engaged throughout the entire piece better than the alternative.

This retention graph compares how listeners responded to two different episodes of a science podcast, showing the percentage who stuck with the program at each minute elapsed. The episode with a stronger intro, displayed in orange, held listeners better in the first five minutes; the episode displayed in green had a sharp drop in listeners within the first minute and never made up the difference. This trajectory is very typical for all podcasts. The episode with the stronger intro almost always keeps the audience engaged throughout the entire piece better than the alternative.

Besides starting strong, the podcasts that work well on NPR One share another important characteristic: They use techniques to re-engage the audience every 2.4–5 minutes.

When you are creating a radio piece, you can count on a fairly constant number of people listening all the way through it, even if it’s not the same people at the beginning of a story as at the end. But podcasts have their biggest audience at the beginning and smallest audience at the end. (Protip: Never save your best stuff or your most important point for the end of a podcast, because that is when your audience will be the smallest it will ever be.) A great podcast uses storytelling techniques to keep as many listeners as possible through the show.

Unlike radio, your artwork and the language you use to describe your podcast and its episodes are important to your success. Your podcast artwork has to draw people in. The podcast’s description has to function like a headline that makes someone click to listen. We’ve seen great podcast episodes fail to do well because the title and description didn’t entice people to give the episode a chance.

Specifically, when it comes to local podcasts, it helps to think very intentionally about who your audience is and how to reach those listeners.

Stations such as WNYC, WBUR and Minnesota Public Radio are producing podcasts that are geared to a national audience, including Modern Love, In the Dark and Death, Sex & Money. These obviously perform extremely well on NPR One and beyond. But podcasts that are telling local stories have found success beyond the reach of their stations’ broadcast signals. These podcasts can be case studies for presenting stories that appeal to people elsewhere who are still connected to that place.

St. Louis Public Radio’s podcast We Live Here was created in the aftermath of criminal-justice protests in Ferguson, Mo. NPR One promoted the podcast to the national audience due to the timeliness and interest in the topic. The podcast found a community of interested listeners who wanted to explore issues of race, class, power and poverty. When we looked at listenership data, we found that there were ten other markets where the podcast had more listeners than in St. Louis.

We found a similar story with WUWM’s Precious Lives podcast. It is about the impact of gun violence on children and teenagers in Milwaukee. On one hand, the episodes are about very local specifics. But Milwaukee is not at the only city struggling with this issue. As with We Live Here, a huge percentage of its NPR One audience — 94 percent — came from outside Milwaukee.

The producers of We Live Here and Precious Lives were telling stories about issues facing people in their communities, but these stories spoke to much larger issues experienced in many communities throughout the United States. Both of these podcasts point to ways of using specific stories about your community to highlight an issue that will have national resonance as well.

We’ve also seen stations find success with podcasts that build on inherent interest in their community. For instance WWNO’s Eve Troeh created the limited-series podcast Katrina: The Debris with the idea that New Orleans is a “city with international reach because so many people have visited.” These are people who would want to check in and learn about how the city is doing ten years after Hurricane Katrina. She says it made sense for WWNO to tell this story because “we are an authentic voice for people who care about NOLA.”

Likewise, WBEZ’s Curious City podcast also benefits from the fact that a lot of people have lived in or visited Chicago and feel strong connections to the city. The podcast’s focus on very local stories about Chicago makes it interesting to people outside the city limits or the contours of WBEZ’s broadcast signal because it helps these listeners maintain those connections.

Both of these approaches allow stations to create podcasts that are local but have potential to attract an audience that’s large enough to tap into sponsorship revenue.

Rethinking local content

Before Sara Sarasohn left NPR One, I spent a lot of time looking at the data with her and thinking about what it meant for the future of local content. NPR One data shows us how people react when they encounter the different types of local content that stations have traditionally produced. Our conception of local content has been defined by broadcast towers and the geographic reach of a station’s signal.

But the podcast data from NPR One also points to a new way of thinking about local. With digital platforms such as NPR One, stations can provide coverage about the topics that they have unique expertise in reporting to people anywhere.

This can mean making the most of a local issue that acts as a lens for examining a larger trend, as St. Louis Public Radio and Milwaukee Public Radio have done with their podcasts. It can mean becoming the voice of your community for people who consider it their hometown or their true home regardless of where they actually live. And it can mean defining your station by owning an issue or topic, as many newsrooms are doing through the journalism collaboratives they have created around topics such as agriculture and energy.

There’s no shortage of great local stories to tell in your community, whether you are telling those stories for the people in your terrestrial listening area or beyond. NPR One data provides clues for how to tell those stories as effectively as possible so that your station can have the biggest impact possible with the local work you do.

Tamar Charney is acting managing director for NPR One. A former program director at Michigan Radio, her public radio career has included working as a newscaster, reporter, producer and creator of talk shows.

[…] is actually at its highest in the first 5 minutes compared to any other time during an episode (from NPR One, […]

I don’t react with “interesting” or “share” buttons because then NPR ONE will start sending me ALL the content from this local station in upper Michigan or upstate Nee York with NO WAY for me to tell NPT that “No, I don’t WANT so many stories about these places. I get sports and weather stories now that I have to skip. Any assumptions from your data need the huge caveat that the App controls and curation are terribly inaccurate. I get a high proportion of absolutely irrelevant local stories from places I don’t live. I have to skip them or listen to other content because at some time I “liked” some of their stories. The user’s ability to correct wrong data makes your data garbage. How do I register my strong disagreement with content curation? You can’t make your assumptions using that bad of an input tool! !