Anna Sale on podcasts: ‘People feel a relationship with the show’

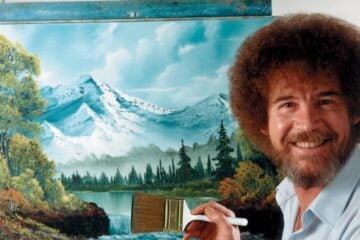

Sale (Photo: Amy Pearl)

Launched in May of 2014 — five months before Serial — WNYC’s Death, Sex & Money was one of the first hit public media podcasts that wasn’t also a radio show. In interviews with both well-known and unknown people, host Anna Sale finds ways to painlessly pry out the most intimate, revealing details imaginable about their lives. In an interview on Current’s podcast The Pub, recorded live at the Online News Association conference in September, Sale talked about how the podcast got started and much more. This is an edited transcript.

Anna Sale: Death, Sex & Money started because I got an email while I was sitting at my desk covering politics in the WNYC newsroom that there was an invitation for anybody who worked at our company to submit a show idea. There was going to be a contest, and finalists would get an opportunity to pilot a show. I was a little tired of covering politics and knew that this was an opportunity that I didn’t want to see pass me by, but I didn’t have a show idea.

So then it became this process of walking the dog, thinking, writing down, scribbling notes and figuring out what I really — if I could do anything — most wanted to do. And it was to have intimate conversations around the things that I was having difficulty figuring out in my life, the things that I think other people had difficulty figuring out in their lives, but didn’t feel like there was a safe space in the public conversation to explore them.

Current: Had you done the kind of interviews that you now do on Death, Sex & Money in the process of being a political reporter that maybe couldn’t make it to air?

Sale: They did make it to air. One of the most important stories, when I was covering the mayoral race in New York City, was an interview with Bill de Blasio about the suicide of his father and his father’s alcoholism. In the context of the race it made sense, because his family had become a big part of the narrative of his campaign. So we did an interview, and it went up on the air. We did a longer version that went out online, and I think it really helped me see, “Oh like this is what I’m best at, and I want to do more of this kind of interview.”

Current: That’s the prototype for Death, Sex & Money right there. You did an episode about cheating; it’s, like, the best episode. Here is a clip in which you ask the most unfathomable question. This is the question that you do not ask — ever. You’re talking to a guy who has this relationship pattern — he’s always the other man — and halfway through this clip, you ask this guy something that I would never have been able to ask.

Sale (speaking in clip): There’s a pattern that you can look back on your life and see that you’ve been with a series of women who weren’t available to be just with you. It sounds like you haven’t quite figured out why that is.

Male voice: Yeah, well I’ve got reasons why I believe that. Physically, I’m an overweight guy, so I feel like that’s probably why I can’t be the number one choice. They may love my sense of humor and my kind of compassion side and the fact that I’m not afraid to let out my feelings and tell them different things. All that loses to the fact that I’m not 6-foot-4 and have rock-hard abs and look fabulous or something.

Sale: How tall are you, and how much do you weigh?

Male voice: I’m 6-foot-1, and I’m very happy to say that I’m about 295 right now. I lost about 45 pounds in the last year.

Sale: Congratulations.

Male voice: Thank you very much. I’m trying to be done being ashamed of anything about me and just putting it out there and saying, “This is me. This is who I am.”

Current: You asked the dude how much he weighs!

Sale: I did.

Current: And it got you to this beautiful place. From the storyteller’s perspective, it gave you your resolution to your story, which was great. What gives you the gumption to ask that question?

Sale: Because he said, “I’m not this.” And I’m thinking — we were in a studio; I couldn’t see him and I was also thinking about the listener, so “What do you look like and how do you feel like that’s shaped your relationships with women?” So I asked. And then it’s interesting to me that it opened up this dimension to the conversations about cheating and about what people felt like they deserved in relation to the body that I wasn’t expecting at all, and it was actually a theme that we heard in several listener stories. That episode about cheating was all derived from emails and voice memos that we got from listeners. But when I left that interview, I thought, “Very brave of him.”

Current: I just want to listen to one of the quick clips from the cheating episode. This is when you were just right there with the perfect question. You’re talking to a lady who is a biologist, and she used to think that monogamy was unnatural. But then she had to put that theory into practice because she caught her boyfriend cheating, and she really just couldn’t handle it and they broke up.

Sale (speaking in clip): What do you think you’ll say the next time you have a conversation with somebody you’re beginning a relationship with? What will you say about your expectations?

Female voice: I think I want to make sure that the person that I’m with can answer the question, Do you know what you need to be happy?

Sale: Do you know what you need?

Female voice: More so now than ever.

Current: You immediately turned her question onto her. That is some deep, like, seventh-level black-belt ninja listening that you’re doing right there as you’re interviewing. Tell me about the headspace that you get in when you interview people.

Sale: That interview also was one that wasn’t in-person, and it’s a slightly different process when you’re with someone than when you’re not in the same room. But when you’re not in the same room, I hear her say, “This is what I want from this person who might be in my life next.” And I’m trying to understand what she’s learned from this trauma of feeling really betrayed. So I knew I needed to know not just what she hoped for, but how she felt like she had been changed. So that was why that pivot happened that way. But when I’m interviewing, it’s always about if you say one thing — like in the moment you played before, about, like, “This is what I’m not” — it’s how am I going to make it concrete. “You need to tell me more so I can understand and see it and kind of understand exactly what you’re trying to say.” So it’s asking about physical details; it’s asking about, if someone says, “Yeah, that was a really crazy moment.” Well, what was it really? What was it like? Tell me more about that. Where if someone says, “Like, yeah, we went on this camping trip and all these things happened. . . .” Did you go on a bus together, all of you together? What was it like? And then they have to describe more. So it’s just about continually trying to make it more concrete so that I can understand, and then that also really helps with the storytelling because it makes it more vivid for the listener.

Current: People have compared you to Terry Gross in the sense that you’re the person who gets things out of people that other interviewers don’t get.

Sale: That’s an honor; she’s my hero. Give it up for Terry! [applause]

Current: You’re both kind of like Barbara Walters, but with dignity.

Sale: Aww, Barbara had a long career. Let’s be respectful.

Current: No, you’re right, I’m sorry. But what do you do to communicate to people that they can open up to you?

Sale: At the very beginning of a Death, Sex & Money interview, I say, “The show is called Death, Sex & Money. Thank you for agreeing to this interview.” But I say, “The reason it’s called that is because it’s really about trying to strip away the things that we don’t talk about to get to the moments of life transition that we all go through. So if you’re describing something that’s happened in your life that was difficult or a point of transition, I’m asking for details because I want to help other people understand. And so if there’s things that I ask you that you’d rather not talk about, the show is edited, you can tell me you don’t want to go there.” But I really try to help my guests sense that I’m not asking questions to just be provocative for the sake of being provocative, but because it’s about trying to find those emotionally resonant dimensions.

Current: To me as I listen, and if I imagine myself being interviewed by you — which, let’s hope that doesn’t happen, ever — I imagine that the timbre of your voice would actually help. It’s so lovely but it’s not so incredibly gorgeous as to be threatening . . .

Sale: Thank you. [laughs]

Current: Sorry, I mean it’s a voice that I want to talk to.

Sale: Yeah, I think that that’s actually really important, and it’s something I learned early on as a young woman reporter, that I could use my non-threatening-ness to my advantage. It’s not that I’m being mercenary about it, but I think the show is really about trying to understand and trying to pull out. There’s sometimes moments where — I was talking to some listeners — we did a meetup in L.A. a few nights ago, and one listener was just like, “I just can’t believe when people say these things you, I just want to go, ‘What the hell? How could you do that?’ And you just go, ‘Tell me more about that.’” And I think it’s part of my personality that my first impulse is to really try to understand and kind of pull out the story and the narrative and not go to the place of judgment. But it’s a constant sort of thing; I’m trying to make sure I’m not letting people off the hook, as well.

Current: Here’s a clip from your interview with football player Domonique Foxworth.

Sale: It’s one of my favorites. I love that episode.

Current: I love this because you ask him this question that I think a lot of people will regard as kind of a softball or frivolous or just something to get where you’re trying to get him to some kind of cheap fun college sex anecdote. But you stick with this line of questioning and it gets you to someplace really intense, really meaningful. This is a couple of minutes long, and I should say that I cut it down a little bit.

Sale (speaking in clip): What was life like in the dorms for you?

Foxworth: I don’t know. It’s definitely a different experience than the average freshman, because you’re kind of a celebrity on campus.

Sale: What was it like to be a celebrity on campus with women?

Foxworth: There were some easy opportunities, or lay-ups as I was an 18-year-old guy. I mean, forgive me, I hope I would get a chance to get into a conversation about the more mature . . . and a better perception on masculinity than racking up numbers. That’s how I thought when I was when I was 18. Forgive me. When those opportunities presented themselves, there was a specific type of person who was looking for you. Those are not the type of people that you’re necessarily looking for for a long-term relationship, if that makes sense.

Sale: It’s an extension of fandom.

Foxworth: Yeah, I think there is probably a racial component also, and going to a predominantly white school it’s like these women who wouldn’t necessarily be interested in you as kind of a long-term relationship type of person. . . . Well, this big kind of like Mandingo-strong black man, let’s experiment with that and see what this is all about.

Sale: Were you aware of that at the time or looking back?

Foxworth: I think I was aware of it at the time, or I kind of used it to justify some of the things that I would do. So I wasn’t like the best boyfriend or the best everything at the time, and I think I would use things like that, like, they’re just after me because they just want to be close to the football guy. Or they just think that I’m in great shape and I’m like this stereotypical oversexed black male — they want to give that a try, but they don’t actually want to take me seriously. So I mean, whatever, I don’t care if I am with her and her friend and don’t think much about it. I think I was aware of it to the extent that it gave me cover.

Current: Shit got real there. Were you ready for that?

Sale: No, I was like, “Whoa, we’re really talking about this,” and I really liked that he brought in the racial dimension of being a star athlete on a college campus and probably white campus. What he was saying is, “I felt objectified and dehumanized, and so I objectified and dehumanized women” — and that’s something that happens a lot in sexual relationships. I was just so appreciative that he was willing to be honest.

Current: What made it one of your favorite interviews?

Sale: I love that interview because I’m from West Virginia and I grew up loving college football and the West Virginia Mountaineers. And when you love a college football team, you love these players for four years, and then you kind follow them as they go into the NFL, but otherwise you sort of stop knowing their stories. And to hear Domonique’s story of growing up from the age of like 7, and starting training knowing he wanted to be a professional football player. And now he’s in his early 30s and with the time he was at Harvard getting his MBA after leaving the NFL, just to hear his story of what it was to be recognized as a teenager that you were going to be one of the special ones that was going to make millions, and how that changed his college career. How it changed his relationships when he became a professional athlete and most of his teammates at the college level didn’t. How he felt when he was working for the union for the NFL. He was one of the union reps, and the way that he felt interacting and negotiating with owners and ultimately realizing, “These guys aren’t that much smarter than I am. What is this?” And ended up feeling pretty OK when he got injured and needed to leave the league.

We hear that these professional athletes are just so much a part of American culture, but we don’t hear these stories at that level of detail. So I loved it; I loved it that he was willing to just go there with me.

Current: One difference between you and Terry Gross is that primarily Terry Gross is interviewing celebrities, or just people who have chosen to be in the public eye for one reason or another. You do celebrity interviews, but you also just talk to a lot of “normals.”

Sale: We sometimes say “everyday people.” We said “everyday people,” and now we say “people who are well-known” and “people who aren’t well-known.”

Current: So is it easier for you to interview people who are well-known versus people who are not well-known?

Sale: It’s a really different thing. The challenge with people who are well-known and who’ve been in the media spotlight is that they’ve said all of their clever anecdotes many times. And to be a revealing interview, you’ve got to cut through some of those, so it’s figuring out the angle. We do a lot of that when we’re pitching; it’s like, what might they be willing to talk about that they haven’t talked about a lot? And we try to get celebrities who aren’t on book tours, who aren’t in the promotional cycle, so they’re not immediately going to the talking points that they have rehearsed and are saying again and again.

Current: That’s a thing because I’m someone who, because I hate myself, I read a lot of comment threads on NPR.org, and you see that one of the conspiracy theories that people have out there is that they think that people are buying their way onto NPR so they can promote their thing, as evidenced by the fact that they happen to have a book out. Kim Kardashian happened to have a book of selfies out when she was on Wait, Wait . . . Don’t Tell Me! But in fact that’s not how it works. We get them on their promotional cycle because that’s when we can get them; that’s when they are available. So how do you get them?

Sale: When we first launched — in piloting, actually; the show didn’t exist yet — we got our interview with Jane Fonda. That was because she’d written a book that came and went but came out of her activism around adolescent health and adolescent sexual health; it was called Being a [Teen], and 76-year-old Jane Fonda had just published a book called Being a [Teen]. So we contacted Random House and said, “Could we talk to her about what it was like when she was a teenager, and also some other things?” and they were like, “Yes.” That’s how we got that interview, because it was a small book and we knew that that —

Current: She was right on topic for you, as well for the show.

Sale: Yeah. And then in another episode, Ellen Burstyn, who’s an actor who’s in her 80s and she wasn’t working on any projects at the time that we did the interview, but she lived in New York and we just pitched like, “Here are the things that we know about your life, and here the things we want to talk to you about, and here’s why.” We were just lucky enough that she said yes and got to interview her in her apartment along Central Park West. We get a lot of no’s, but you just pitch the people who — you say why I want to talk to you about this thing, and you try to give thoughtful pitches. And sometimes they say yes.

There are people on Death, Sex and Money who aren’t famous. When we were coming up with the show, I didn’t think about celebrity interviews as part of the show. It grew out of doing voter interviews and covering politics and knowing that there were incredible personal stories of people that, they fit in the top anecdote of a story about polls and why this person was leaning towards Obama versus Romney, but you didn’t get to hear the full story. I was having these incredible conversations with people and learning a lot, but a lot of that didn’t fit in the narrative so it wasn’t going on the air.

So that’s what I wanted to do; I wanted to include those stories, because I think that you can just get really good stuff. And the listener-generated episodes were a total surprise, and those are all people who aren’t famous. We just ask a really broad question like, Tell us your stories about cheating. And a really incredible gift of podcasting is that people feel a relationship with the show, so much so that they will send really personal stories in.

Current: And they happen to be walking around with an almost broadcast-quality mic in their pocket, most of them, and they send you voice memos.

Sale: Yeah, my favorite voice memos are when you hear, like, windshield wipers going, and you can tell someone was driving home at the end of the day, and there’s, “I’m just going to leave my message for Anna at Death, Sex & Money while I’m doing other things.”

Current: What’s wonderful about you as a producer, and your team, is that you get those voice memos and you could just follow up with that person and book a real interview with them and often you do. But you also work in the original voice memo, because that has an intimacy and an immediacy that the other tape just doesn’t have because of the solitary aspect of it, where it’s someone talking by themselves to the disembodied you; you’re not even there.

Sale: Yeah, I mean, picture that; picture someone in a room by themselves talking into the end of their phone because they have a story to tell and they need to share something. That’s good tape. And so we try to use those a lot in those episodes.

Current: It’s called Death, Sex & Money. One of those things people like to talk about a lot more than the other two, especially when they’re a little bit lit, as we are this evening. Do you find that audience-response rates are higher for the sex episodes? Is it easier to get people to talk about sex, as opposed to death and money?

Sale: I would say easier to talk about, but people feel a real need around it. When Death, Sex & Money first started, the reason the cheating episode came about was because, immediately, that was the story that we were getting in our inbox. Like this really pivotal thing happened in my romantic relationship, and this happened as a result of that. Questions of gender and sexuality: Those come up a lot. But money also comes up in the inbox, more than I would expect. But definitely the thing that’s the most difficult to get people to talk about with specificity is money. That’s harder than death and sex.

Current: Scariest thing of them all.

Sale: Yeah. Well, it’s also like we don’t have any common language around how we talk about where we fit —

Current: And it’s rude to talk about it. It’s all right to talk about sex in some social circumstances, but in this social or social circumstance that we’re all in right now, if we talk about sex it wouldn’t be that weird.

Sale: I think it would be weird.

Current: I guess you go to different bars than me.

Sale: Lulu Miller from Invisibilia — I got to know her more once we sort of landed into podcasting. But one thing she said to me when I met her at a conference, she was asking where I was from, she was asking about my family and just really trying to kind of get me. She’s just like, “I’m just really trying understand how you were raised because the things you ask, I would never ask.” And it kind of caused me to contemplate whether I just didn’t have any manners. But I think a lot of it comes from having been a reporter and having to be the kind of reporter where you have to shout rude questions at Anthony Weiner when he has a sex scandal. Like, “Why should we trust your judgment?” But the muscle that you develop when you’re a reporter is asking the straightforward question that any person who had good manners, they would not ask it.

Current: Former NPR sports correspondent Mike Pesca has this great podcast now for Slate called The Gist. The other day he was talking to this guy about pizza. He made this just epic analogy connecting pizza and radio shows and it made me think of you, for reasons that will now become obvious.

Pesca: Let me say this, a good pizza is I think like a good radio show. I’ve noticed this, that any time a committee tries to start a radio program, it never works. But when one guy, one guy like Ira Glass, one Howard Stern, one person saying, “This is my vision,” that’s a good — sometimes it’s a huge train wreck, but that’s the only way to get a transcendent slice of pizza or a good radio show, I think. I think that makes sense.

Current: Does that describe your show? Is this the show that you’ve always been wanting to do and then finally somebody cut you loose and you could just do it?

Sale: I thought about a lot, like, where did this come from and . . . I started at West Virginia Public Radio in 2005. And then I worked for Connecticut Public Radio, WNPR. And then I moved to WNYC. And I was always, before hosting Death, Sex & Money, in a newsroom, so I was doing the things you get to do in a public radio newsroom, which is cover news and do the occasional in-depth feature that’s off the news. And always stories about people’s personal lives and the details of how they got from here to there and what they’ve gone through. That always was the thing that I went to. Like the bluegrass musician that I interviewed my first year at West Virginia Public Broadcasting, about why he moved back to West Virginia from Boston, where he was successful, after his son died — that could have been a Death, Sex & Money episode. So it was always there, and it’s always been the stories that I’ve been drawn to.

But a really cool thing that’s happening now is like when you go through the piloting phase, that that is when I felt the most isolated and terrified, when WNYC said, “OK, try this.” And it was me in a corner with a laptop, and I just learned Pro Tools. Emily Botein, my editor, sat me in a conference room and taught me how to use Pro Tools, because I had always used other audio editing software. And it was just figuring out what was the sound going to be, who were the guests, and I had this huge blank slate.

So that was really figuring out what my voice was going to be. But now we’re at a phase where I have an incredible producer, Katie Bishop, who has very clear, strong opinions of her own. Emily Botein is an incredible, precise editor, so it feels more like a team and more and more like it’s less my vision and it’s definitely our vision. And it’s the vision of the listeners as well because they let you know if they feel like you’re deviating from what they’ve come to expect from the show or if something is felt like a dodge, when I should have gone harder-hitting.

And the listener stories have definitely been all from the people who’ve come to think of Death, Sex & Money as a community. So I feel really proud that I get to be the voice and the convener of this, but it definitely feels like it’s a collaborative process.

Related stories from Current: