Tag: CPB

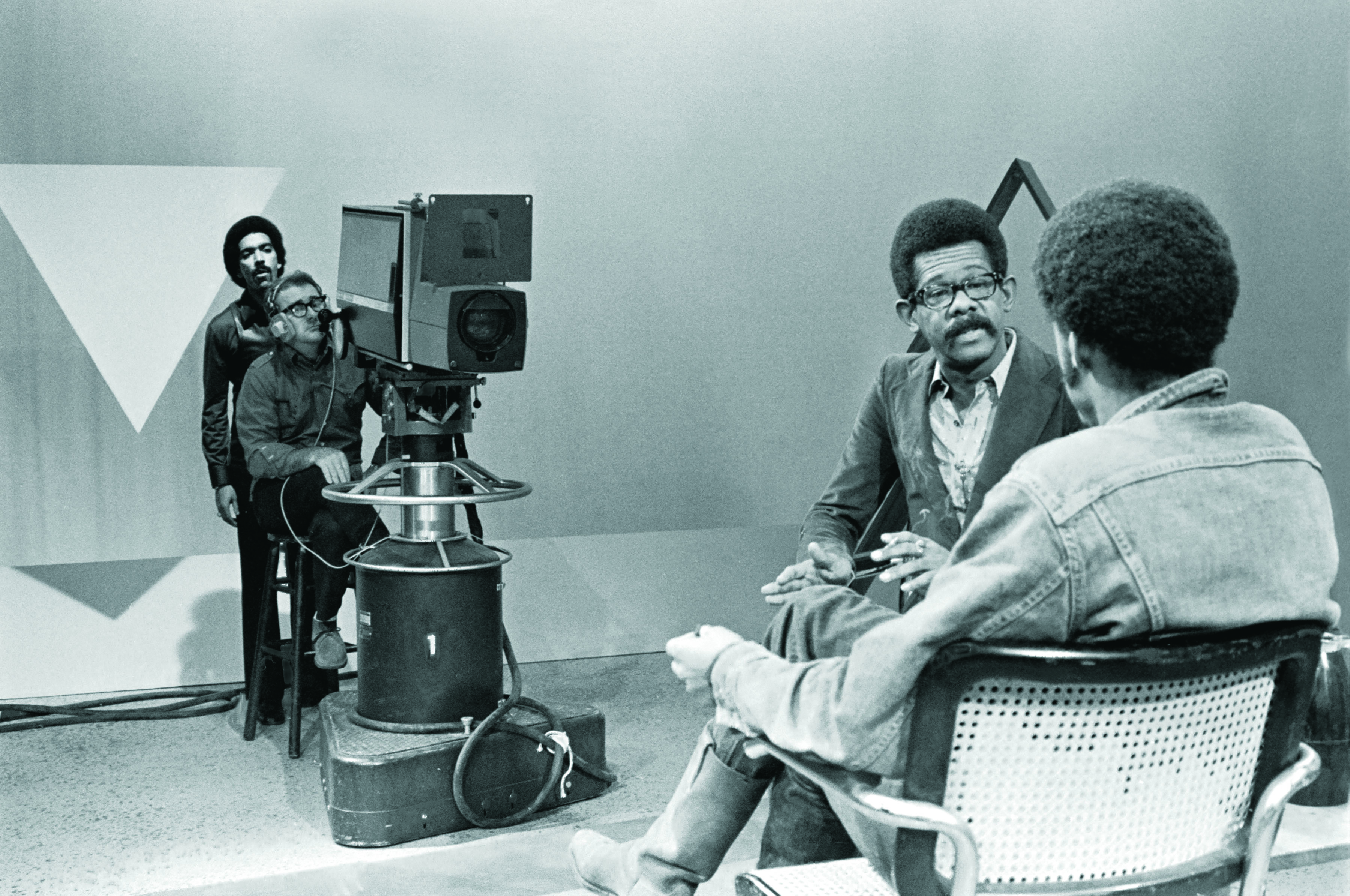

The last days of ‘Soul!’: Why a trailblazing show about black issues couldn’t last

An excerpt from a new book looks at the shifts in funding that doomed the documenting of an era.NPR journalists recognized for coverage from conflict zones

CPB honored David Gilkey and Ofeibea Quist-Arcton at the Public Media Development and Marketing Conference.CPB to honor NPR journalists

David Gilkey and Ofeibea Quist-Arcton were part of the NPR team that covered the Ebola crisis earlier this year.After rough start, Southern Education Desk relaunches with tighter focus

The Local Journalism Center brings together a new group of stations, buoyed by a third year of CPB support.House and Senate spending bills propose level support for CPB, but no interconnect funds

The bills include level funding of $445 million for CPB.House Appropriations Committee approves $445M for CPB

But PBS’s interconnection project lacks support so far.U.S. pubcasters visit Kiev to advise on creating public media network

Representatives from CPB, Oregon Public Broadcasting and the Association of Independents in Radio are in Ukraine's capital.FCC to provide spectrum bids to stations by September, CPB Board hears

Stations have 60 days from receiving bids to declare whether they will participate in the auction, set for mid-2016.A CPB board member urges pubmedia to fill void in local news

“Local journalism is a niche that is being neglected by the commercial marketplace.”CPB finds majority of audited grantees out of compliance with Communications Act requirements

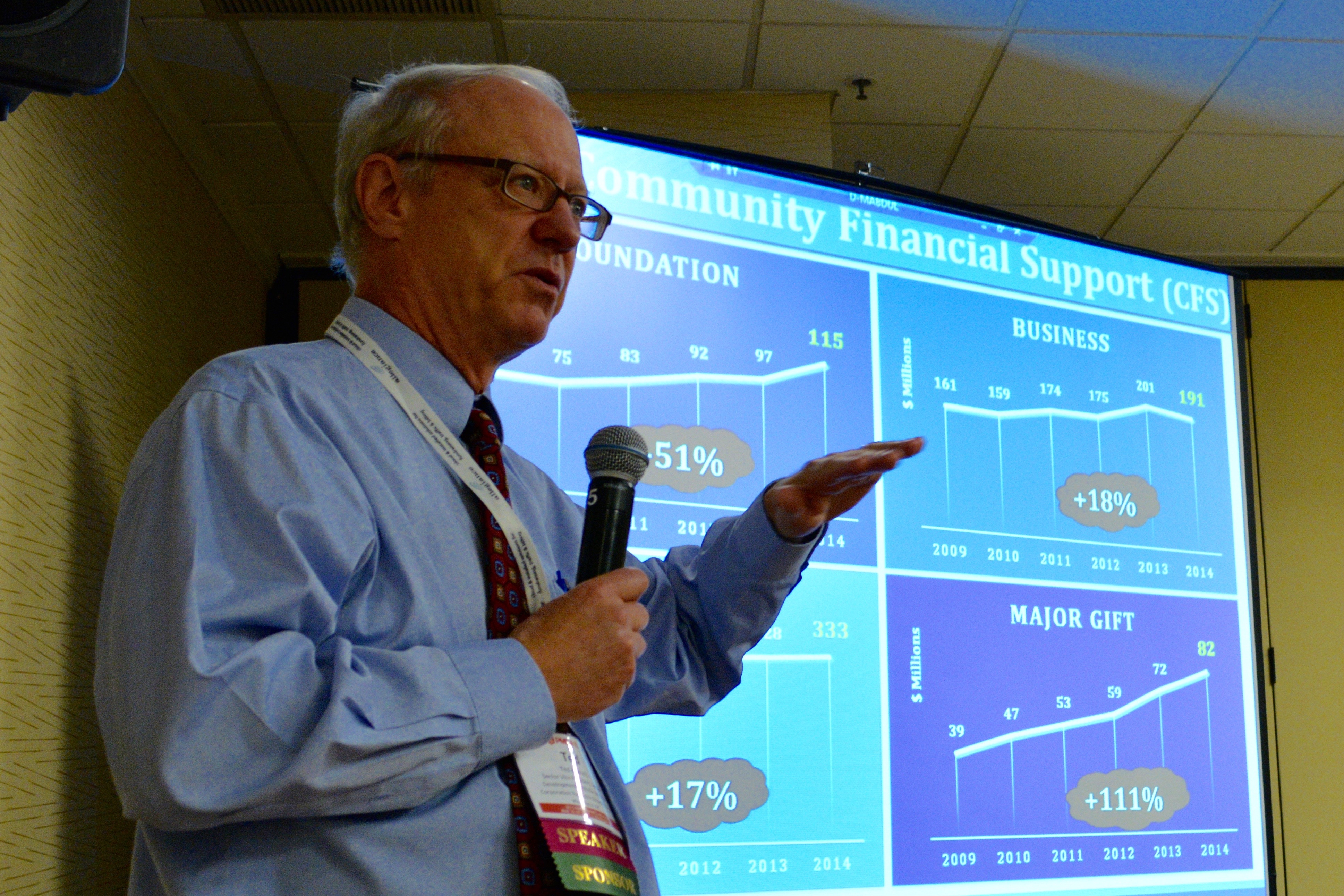

Two-thirds were noncompliant with at least some provisions of the Act, according to the corporation’s Office of the Inspector General.CPB analysis shows bright spots for public television

The analysis found public TV stations rebounding from five-year declines, as well as slowing growth for public radio.CPB backs collaboration in Baltimore on coverage of Freddie Gray aftermath

Two stations are working together to expand reporting on the city's response to Gray's death.Senate resolution upholds forward funding for CPB

The joint resolution approves the blueprint for the $3.8 trillion 2016 federal budget.CPB finds room for media innovation in 1967 Public Broadcasting Act

CPB’s fresh look at the Act is part of its two-year “Future of Public Media Initiative.”CPB’s Curren to retire, Reveal expands, and more comings and goings in public media

Curren has been CPB’s c.o.o. since 2006.