Tag: Children’s programming

Boston station adds new podcast for kids

'Circle Round' launches in September.Louisville Public Media gets grant for kids’ classical podcast

The podcast aims to be a resource for schools lacking music education.For kids TV, CPB focuses on diversity behind the screen

The funder is ramping up efforts to boost minority staffing on the shows it funds.Two Michigan stations join to create children’s programming channel

WKAR’s licensee has decided not to give up spectrum in the FCC auction.Linda Simensky, PBS’s head of children’s programming, on carrying forward Mister Rogers’ legacy

“Shows are being made today from a much better understanding of how kids learn.”The Pub, Episode 6: WWFD (What Would Fred Rogers Do?), PBS documentaries in danger, David Carr on ...

This week, we contemplate how much children’s public television has changed since Fred Rogers’ day, and the news isn’t all bad — ...PBS’s live-action Odd Squad aims to ‘make math relevant’ for kids

PBS Kids will expand the footprint of its math-focused programs with Odd Squad, a live-action TV series for school-aged children. The new show, which ...Odd Squad to be PBS Kids’ newest math learning series

It’s a question that parents and teachers struggle to answer at home and in the classroom: how do we make math fun ...PubTV tests new approaches for fundraising with kids’ TV

This reluctance to fundraise around children’s shows is “a conundrum,” Rotenberg said in an interview. “Kids’ programming is probably the most recognized ...It’s a beautiful day for return to Make-Believe

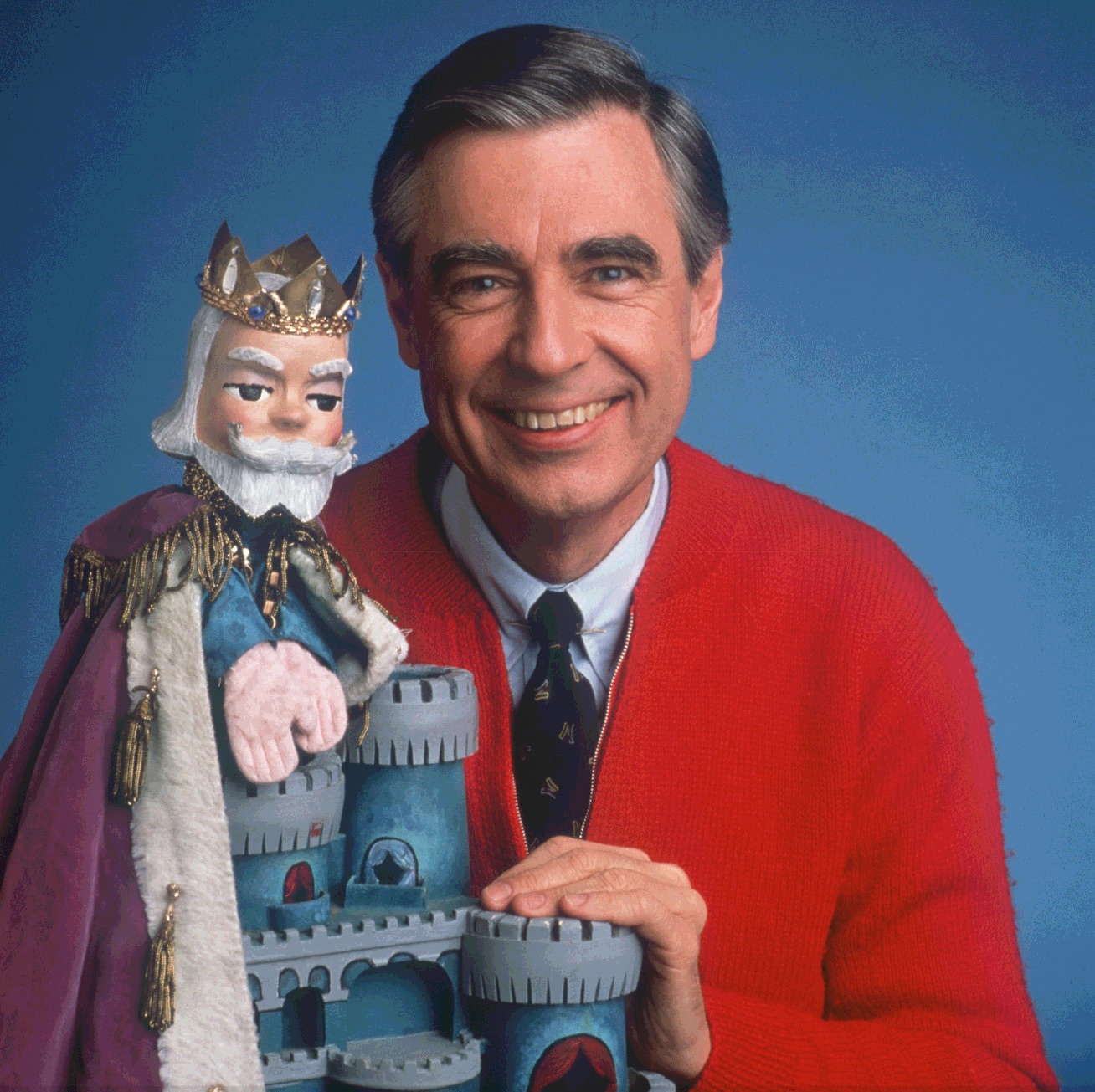

In honor of its 40th anniversary on public TV, the famous Mister Rogers Neighborhood of Make-Believe set, including King Friday XIII’s castle, ...Young promoter cancels his debut as Fred Rogers’ successor

Michael Kinsell, who planned to present himself as the next Mister Rogers at a controversial gala on Sunday in San Diego, told Current ...It’s all been good for whatshisname since he was rejected by the dump

A wayward, 6-foot stuffed gorilla arrived at WDSE-TV in Duluth, Minn. in time for the annual Kids Club Circus last week. Its ...Many stations packaging their own kids’ channels

With the all-digital future arriving, if haltingly, and a bigger share of viewers likely to come through DTV multicast channels, ...‘Electric Company’ returns, Naomi still missing

A new Electric Company, based on that 1970s PBS hit, premieres Jan. 19.Here I am, your special PBS Kids Island (come to me, come to me)

PBS Kids Island, an online amusement park located on the Raising Readers website (www.readytolearnreading.org), offers learning games created by producers of Super Why!, ...