ITVS study explores the complex relationships at the heart of documentaries

microgen / iStock

Why would anyone want to be in a documentary film? Why would you share your story with both filmmakers and viewers — and put yourself at risk in doing so?

“The Filmmaker-Participant Relationship Unpacked,” a study recently released by the Independent Television Service, sheds some light on these questions. The report addresses the ethics and accountability of the documentary practice, specifically the dynamics between filmmakers and on-camera participants.

The subject has driven conversations throughout the documentary community over the past several years. But the study, released in November, digs deeper into the concerns of the 678 U.S.-based documentary filmmakers and 195 participants who contributed their observations. Participants discussed why they agreed to be in a documentary in the first place, how the experience impacted their lives, and why they would — or would not — do it again. Meanwhile, filmmakers cited such challenges as limited resources, funder requirements and distributors’ standards and practices.

All told, the study provides a comprehensive set of findings that address duty-of-care considerations in the documentary practice for filmmakers, programmers and audience members alike.

According to Grace Anglin, the study’s principal investigator and ITVS’ director of research and evaluation, the ITVS team was most surprised to learn that 89% of documentary participants indicated that they would participate in a documentary again to, as one respondent put it, “educate, inspire, and motivate others to take action.” In a presentation of the study at SXSW in March, Anglin noted that participants “spoke powerfully about the ability to bring to light important issues, to highlight their community and to help alleviate feelings of isolation.”

One respondent shared, “The impact that the film had was well worth the time, energy and challenges that came with participating with the film. Lives have been saved. Systems and mindsets have been transformed, and new approaches to the work have been created as a result of the film.” (The study did not name respondents or the films they were involved with.)

In addition, Anglin noted, “95% of those participants indicated that they had a really high degree of trust with the filmmaker, that they really felt respected in that relationship.” While filmmakers retained editorial control of their work, many participants had some agency in what could be filmed and in providing feedback on cuts of the film.

Of the 11% who indicated that they would not participate in a documentary again, many said they were misled or lied to. “The story has been distorted,” one participant said. “It made me angry because it was such a sensitive and traumatic episode in my life.” Another shared, “The people I spoke with about the documentary claimed they wanted to represent facts and clear up misconceptions. Instead, the series created a firestorm of controversy due to its lack of historical accuracy. It hurt my professional reputation, and it felt like a friend stabbing me in the back.”

Some participants also cited problems with transparency about the filming process. “The vast majority of participants said they understood why the filmmaker was making the film, why the filmmaker was asking them to take part in the film, and the specific role that they would play in the narrative,” Anglin said. But some respondents said they felt pressured to emote on camera, take part in reenactments or recount a particularly traumatizing experience several times. “A lot of what you see in the documentary is honestly just staging,” one respondent said.

Anglin also pointed out that some participants expressed confusion about the business side of the relationship, particularly around consent, distribution and the risks involved in participating. “I think we heard more about that than we anticipated,” Anglin told Current.

According to the study, 30% of participants did not understand whether or not the filmmaker could sell or license their story further, and 39% did not know whether they would have access to use the footage or the final film for their personal use before filming started. One participant said, “I can’t get a personal copy of the movie once it’s sold. And I was totally unaware of that. How could you give years of your life to the film and you can’t even get the finished product without trying to bootleg it off the internet yourself?”

Regarding personal risks, as well as implications for participants’ family, friends and communities, one participant noted about release forms, “The release is only about giving our permission to be filmed, to have the camera on us. It does nothing to protect us.”

As Anglin noted at SXSW, “This quote summarizes something we heard from a lot of participants, as well as some filmmakers, where the release process and this idea of consent were oftentimes initially discussed together. The release really is about legally protecting the filmmaker. … A true informed consent process has a completely different orientation that is about the participant and making sure that the participant understands.”

The capacity to go deeper

Two additional principal investigators on the ITVS study — Patricia Aufderheide, professor of communication studies at American University and an ITVS board member, and Sherry Simpson Dean, senior director of engagement and impact innovation at ITVS — are also affiliated with the Documentary Accountability Working Group, an ad hoc conglomerate of filmmakers, nonprofit executives, and educators. (Current is an editorially independent service of the American University School of Communications.)

In 2022, DAWG released “From Reflection to Release: Framework for Values, Ethics, and Accountability in Nonfiction Filmmaking,” a report that explored the need for ethical standards and best practices within the documentary industry, particularly when addressing duty of care for participants. Many filmmakers who participated in the DAWG project had already been developing templates for accountability, framing their engagement with participants as collaborative and transparent.

While the DAWG framework preceded the ITVS study, both evolved at roughly the same time.

“The questions that inspired DAWG around accountability — who gets to make what film, compensation — were circulating in ITVS as well,” said Simpson Dean. “… ITVS really had the capacity to do the work of answering, what are filmmakers doing? What aren’t they doing? And most importantly, what are the experiences of film participants?”

ITVS, which was incorporated as an act of Congress in 1988 as a production service for independent producers under the aegis of CPB, has funded and presented over 1,800 documentaries for public media and produces the award-winning series Independent Lens. “Part of our role as a service organization was that, if we were able to take on such a research study, it would be a real service to the industry at large,” Simpson Dean said. “So for all of these people that we touch in public media and in the industry, we felt we had the capacity to do the deeper dive.”

Other media arts organizations such as Brown Girls Doc Mafia, The Flaherty and Documentary Producers Alliance have been doing work in this area as well. Having secured grants from the Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, ITVS could establish partnerships with these and several other organizations to design and implement the surveys, while teams from American University, Columbia University and the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago spearheaded the research process.

According to Anglin, the research teams brought their respective processes and methodologies to the project. Columbia University’s Courtney D. Cogburn, for example, had expertise in social work and health policy, while the NORC team, who focused on focus-group data collection, “had folks who had some experience with film and folks who had an equity-based approach to research,” Anglin told Current.

Navigating a shifting industry

Since the publication of the report, the ITVS team has also made presentations at DOC NYC and a gathering in San Francisco with local public media partners in attendance. “We’ve taken that same approach from the inception of the work in the study,” Simpson Dean said. “We want to be able to present these findings as research for the consumption and review of the industry at large. … Each time we present the findings, we can talk a little more about where we’ve been with it. It’s been contributing to the evolution of ideas for us.”

Given that 40% of the filmmakers had produced work for public media, the ITVS team has been discussing scenarios for presenting their findings at an interactive workshop at DC/DOX in June.

Tamara Gould, CCO at PBS SoCal in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, held executive positions at ITVS for 18 years before joining PBS SoCal in 2023. “I know a lot of the thinking that went into this,” Gould said of the study. “The practice of documentary making had really changed. That just raised a lot of questions, like, what is an ethical practice? … That’s what you see in the report. … It’s a framing tool to consider ethical standards that maybe stations aren’t thinking about as they’re posting content.”

As far as what Gould has heard from her contemporaries in other regional PBS stations, “I haven’t had specific conversations around this study, but I know that my counterparts are all guided by the same desire to be a trusted partner for both creators and audiences. … We all benefit from [ITVS’] … depth of experience with filmmakers. I think chief content officers in other markets, big or small, would feel the same way.”

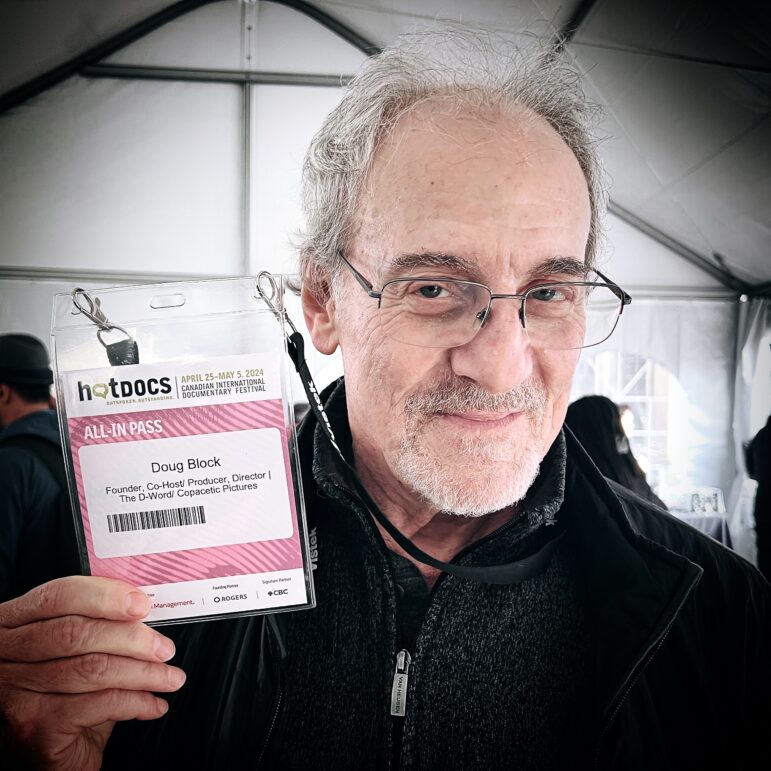

Doug Block, a veteran documentary filmmaker of some 30 years and founder of The D-Word, an online forum for documentary professionals, said in an email that he was glad the study was done and that the issue of filmmaker-participant relationships is “critically important.” But Block concurs with a filmmaker in the study who said they were “against blanket prescriptive best practices, as each participant and relationship is different and complex.”

“The filmmaker-participant relationship is actually part of a threesome, which includes the audience, as both the filmmaker and participant want the audience’s favor,” Block said. “And that complicates matters even further.”

Journalistic standards and ethics should be “par for the course” in documentary filmmaking, said producer/director Laurens Grant (Jesse Owens, For All Humankind, Future of Work, Black In Space: Breaking the Color Barrier), who earned a journalism degree and worked as a foreign correspondent before shifting to a documentary career.

But the expectations of participants and filmmakers have changed as the industry has evolved, she said in an email. Participants expect more, she said, while filmmakers are under more pressure to get “OMG” interviews “at all costs while often navigating constantly shrinking budgets,” she continued.

“So much uncertainty in our industry has just put more pressure on these relationships,” she said. “…The filmmaker-participant relationship is really crucial and we need to preserve and protect it, even though the documentary landscape continues to shift around us.”

Lisa Leeman, an advisor on the study as a representative of the Documentary Producers Alliance, has made ethics an essential part of her practice as both a filmmaker and an educator at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Studies. “I was impressed by the rigor of the ITVS survey design and the analysis of the results,” she said in an email. “I recommend all doc filmmakers read the study’s full findings—it throws down the gauntlet on ways we can practice a stronger ethics of care for the people in our films.”

Leeman added, “While we filmmakers should raise the bar in our own practices, we need funders and distribution platforms to consider how their requirements, implicit or explicit, may compromise participant care.”