Get tips on using generative AI to streamline workflows and boost creativity

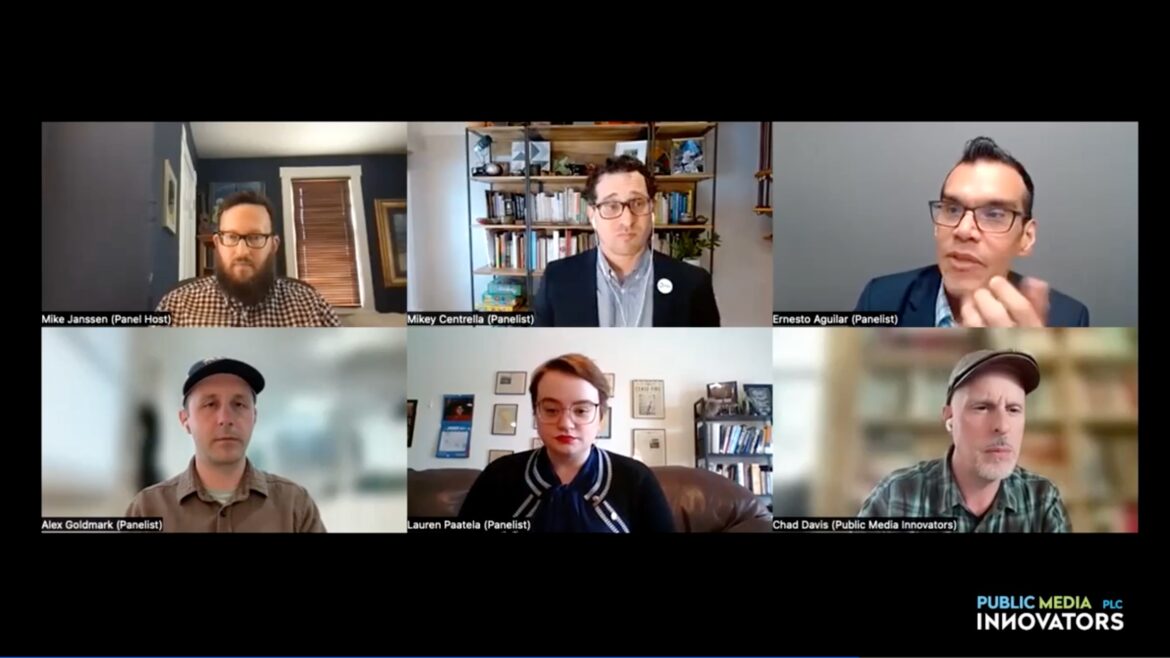

Presented by Public Media Innovators, a NETA Peer Learning Community, the Jan. 18 webinar “Innovate With Current: A Live Users’ Guide to Generative AI Tools” dove into the heart of how people in public media are integrating generative AI tools into their workflows. Panelists shared their favorite tools and approaches for developing creative solutions for everyday tasks, while also acknowledging the potential pitfalls of relying on a bot for a research assistant.

Missed the webinar? You can watch it below or read an edited transcript. We’ve also compiled a list of links to tools and documents mentioned during the conversation.

The panelists were:

- Ernesto Aguilar, Executive Director of Radio Programming and Content DEI Initiatives, KQED, San Francisco

- Lauren Paatela, Video Game Producer, Nebraska Public Media Labs

- Alex Goldmark, EP for NPR’s Planet Money and The Indicator at NPR

- Mikey Centrella, Director of Product, PBS Innovation Team

- Chad Davis, Chief Innovation Officer, Nebraska Public Media

- Host: Mike Janssen, Digital Editor, Current

Mike Janssen: We’re kicking off this Public Media Innovators webinar series by learning about how your colleagues in public media are using generative AI tools in their work. We hope to come away from the conversation with ideas about how you can explore these tools to aid your creativity and make your workflow more efficient. If you haven’t used AI tools that much, don’t worry — you’re in the right place to get started.

Before I introduce our panelists, I just want to point out that today we’re focusing on generative AI. Generative AI is used to create content. It’s powered by language models trained on existing data. It can be used to create text, images, audio and video. But generative AI is just a part of the broader field of AI technologies. Uses of AI that go beyond generative AI include categorizing content, speech recognition or powering recommendation engines.

Also, I’m sure you’re aware of the many ethical issues related to using generative AI. Those include the biases that can be baked into the language models, transparency about when generative AI is being used, and the training of language models like ChatGPT on copyrighted material. We won’t have time to get too deep into those topics today. But if you do have questions about ethics and generative AI, we may be able to get to them during the Q&A portion.

Let’s get started with Ernesto Aguilar. You’ve mentioned that you use AI tools for analyzing spoken dialects of Spanish in audio recordings. Can you talk about how you’ve done that and what tools you’ve used?

Ernesto Aguilar: I assume this is evident but just want to put it out there in case it’s not. Spanish has different kinds of dialects that are spoken regionally, similar to English. And one of those, just to pull an example, is Argentine Spanish, which has particular ways that things are said. For example, adjectives or the way that particular vowels and consonants are verbalized is a little bit different. If you’re one of those folks who hear Spanish and go, wow, that just sounds like it’s coming really fast at me, and it doesn’t really make a lot of sense to you, you may not catch it.

One way that I have used [AI] is to just check my own work around what I hear. I’ve used Pinpoint, a Google tool that is free to all journalism organizations, to upload a piece of audio. It will take that audio and transcribe everything. I can also listen back to it and just check its work to make sure that it’s translating well, and it does do this multilingually. So, it can detect Argentine Spanish. Then I can go, OK, that sounds like Argentine Spanish, but let me check one more time. So I will go to an application like Bloom, which is a large language model that’s also multilingual, and ask it to identify that particular regional Spanish dialect, and it can generally do that fairly accurately.

Argentina is a really good example because Argentina has had a very interesting political history, one that has been dominated by the military, in which — particularly in the 1960s, 70s and 80s — there were many human-rights abuses. The military got amnesty for all those human-rights abuses some years ago that was repealed in the early 2000s. The country is notorious for openly harboring Nazis for a period of time after World War II. So somebody who is from Argentina may have a particular opinion about government and transparency and politics. So if you talk to a source around those kinds of things, it might be really interesting to understand how that experience has colored their worldview and what they say to you. And so understanding those dialects is going to then give you a chance to tell a richer story in terms of content.

Mike: With your focus on serving diverse audiences, you’ve highlighted the potential of using AI tools for translation. What have been your experiences with that and how do you think translation tools could expand public media service in languages other than English?

Ernesto: My newsletter is intentionally for an English-dominant audience. However, I do a lot of interviews where parts or in full, because many of us are bicultural and can switch back and forth, are in Spanish. But I’m going to have to make sure that that’s understood by the rest of the English-dominant audience, and most of us in the public media deal largely with English-dominant audiences. However, we’re trying to make Spanish accessible to them or to ensure that Spanish is translated so that the audience understands, because there are cultural nuances. So most of the large language models — ChatGPT, Jasper, Bard, Bing — a lot of these can usually do multilingual translation … fairly well.

I’ve written about this topic before, and I think this is again evident, but I want to make sure it’s said that these don’t replace staff. They can understand the cultural nuances. However, these tools can be very helpful. What’s intriguing to me right now, and something I’ve been testing a lot as well, have been the Spanish-native AI models where I can put these texts in and see what I get back in terms of English and in terms of how they interpret the Spanish nuances and present it back to me in English. I do see things from Texta, Correcto … Elsa does this a little bit, too. They’re set specifically for language translation. So those might be helpful for organizations that may be looking to explore this.

A lot of these models are still in development. So some of them are not completely there. They don’t replace staff at all. You should certainly bring in the folks, whether you have staff or whether you can hire workers to help you do this kind of work, as I’ve written before. However, they are going to be an enhancement for us who are trying to do this with very minimal resources.

Mike: Let’s move on to Lauren Paatela. Lauren, you said that you’re a big fan of Claude, which is interesting to me as I’ve mostly used ChatGPT, though I have used Claude on occasion. Why do you like Claude in particular and what do you use it for most often?

Lauren Paatela: Before I get started, I just want to give a little bit of a preface here. I’m not a tech-first person. My background is first and foremost in history and now game production. So I’m very much still learning the language of AI. So, if I get some things wrong or I’m not super precise about a lot of the terminology, please be understanding. I like to liken it to driving a . I know how to drive, I can probably teach someone else how to drive and be consulted in that, but don’t ask me what’s going on under the hood or anything like that. I have no idea. So I will happily defer that to someone else who has more expertise in the area.

But as to why I like Claude in particular —Claude is trained with a constitutional AI, meaning that its responses are guided by a set of values and principles. I believe it pulls from multiple different places —sets of principles like the UN Declaration of Human Rights and other sets of principles that make an effort to capture non-Western perspectives in their answers.

I use Claude primarily for a brainstorming partner or kind of like a co-pilot or assistant as I’m thinking about content, thinking about creating things. The most helpful use of Claude and how I use it almost every day is rapid-fire brainstorming. “I want to talk about this. What do you think? Are there any things that I’m missing right now?” Then taking something that he responds and talking about it or saying, “No, not that,” and really quick back and forth. What’s nice about Claude is that he’ll remember all of this stuff. So afterwards when you come down off of the brainstorming, you can say, “OK, so what are some of the decisions that we just made?” And he’ll list all of that. So it’s like having really rapid-fire conversation with someone, and nobody has to take notes or record it or go back.

I also found that Claude is good at finding gaps or things like that. You can feed Claude a lot of material. So I feed him, you know, “These are the goals and values of the organization. These are the goals and values I want to have for this sort of game. And this is the pitch that I’m doing. How does it align with our goals? Is it missing anything? Am I missing any sort of gaps that I should cover?”

Also, I love Claude for summarizing. Historians are sometimes prone to talking and over-explaining. We love the details. We love the extra juicy bits that maybe are not super important, but we still think they’re worth mentioning. When I’m talking about historical subjects, I have so much written for all my sources and research that I’ve done. I feed it to Claude and say, “What are the main points? What are you getting out of this? I know what I’m getting out of it, but what do you think?” So it’s a way to reflect back and improve your writing.

I don’t use Claude for fact-checking or fact-finding. Chatbots will make stuff up. Chad asked me to fact-check information that ChatGPT had come up with … about homesteading in the United States. I got maybe a couple of minutes into it before I realized that, first of all, it sounded like someone who didn’t go to class all semester and then wrote like an essay at the very end. OK, you get the main points, right? But it’s not really saying much. And second, it makes things up using real journals, real names, real books. I got really excited at first because I thought, “Oh wow, all these great resources that I haven’t found on these topics. This is excellent. I didn’t know so-and-so wrote a book about homesteading. This is excellent.” [Those resources didn’t] exist. So I don’t trust it for any sort of fact-checking or fact-finding. … It will make up archival sources, games, stuff like that, and it all sounds super great because it wants to help you find these things, but they don’t exist. So that is a limitation. … So, it’s great for a creative brainstorm. Good for getting you out of sticky situations. But as far as reliable information, you need that kind of human-last fact-checking to follow up on a lot of that stuff.

Mike: That’s definitely a pitfall that people need to be aware of. You’ve also worked with image generation tools to help develop concepts and work with artists. How has that worked for you? What have you done with that?

Lauren: Image generation can produce some really horrific uncanny valley–type images, so it has that kind of entertainment or horror value. But I have used Midjourney, and I was fortunate enough to use it with a 3-D artist in our organization specifically about character design and clothing. For me, as someone who’s not a visual person at all — there’s no images in my brain ever, it’s just words. So I write a description — I work with our game writer as well — this is kind of what the character is about, this is what they’re wearing, this is what’s historically accurate for them to wear and look like. So I’m writing these beautiful descriptions, but whereas that may work really well for the artist — she’ll take that and if she was drawing it, she’d be like, oh, that’s perfect — she then has to interject and say, well, Midjourney or these bots, don’t add in that kind of language. Don’t add in words like “austere” or “severe,” descriptions that help us understand what a character is about. For image generation, less is more. It’s really, what is it? What style? It’s very simple. And from there it’s a good jumping-off point. If you’re doing it yourself or if you’re working with an artist, it’s like a first draft. You get something on the page and you go from there. Do I like this art style? Do I like this character design? Is it getting what I’m trying to say? It’s all about going back and forth and saying, “I’m really sick of this color scheme. Let’s just do a completely different direction.”

Midjourney, I found in particular, has difficulty grasping a lot of complex topics. When I was working on initially pitching the game that I’m producing, Civic Scribble, I tried to do video game–screen, pixel-art style. And the screen and the video, there was nothing that even remotely resembled a video type game. So I went over to Microsoft Bing’s AI through DALL-E and that would give me better results. We hadn’t yet brought in a creative director. This was me pitching my vision for how the game would look, again with limited visual experience and talent. Things like style, amount of pixels, color, the perspective of the game, is it going to be 2-D or 3-D, who’s going to be the characters, and then putting that together and saying, “This is what I want it to look like.” And then working with artists further to develop those kinds of details. Or working with our game developer to say, “Oh, well, the pixels aren’t consistent, the pixel size of the images, right? We have to make that consistent, right?” So again, it’s being able to have something to kind of start the conversation.

Mike: That sounds very useful. Using AI for creating images, you said that the tools also let you see the biases and assumptions that we have today about different historical eras. Can you give some examples of that?

Lauren: Image generation in particular gives you insight into what sources are available about historical eras. Who’s making them? How are they being kept? Are they digitized? Are they able to be pulled from in the first place? So when you use something to reflect a certain historical era or a specific population of people, you have to know what it’s being drawn from and be able to think critically about the sources there.

One example that image generation in general struggles with is being able to understand class differences with clothing or to explore any sort of differences in appearance particularly. It just assumes based on the sources that are available that everything is very high-class. I’m stuck in the 19th century for the game right now. So it’s very Victorian. Everything is perfect and satin and silk, and that’s not the vibe that people are really going for. And so you have to really back off and be particular in saying this is what AI might think about the 19th century, but the reality is [that] is it’s not that way, and we have to be able to recognize that.

One of the characters is a Civil War veteran. And we had a discussion trying to understand the differences in uniforms. Because for a long time the Civil War was “bring your own stuff to the war” for the Union soldiers, so the uniforms weren’t super consistent a lot of times. But the main one was the sack coat. It’s exactly what it sounds like. It’s a sack. But because all of the pictures of Union veterans are generals, typically, or higher-ranking people, they have the full-length frock coat with the fancy buttons and all of the garb and everything like that. So, if you mentioned Civil War uniform, it’s going to pull from that. It’s going to erase most of the people who fought in the Civil War. So you have to be mindful of that.

Another thing is that it makes everyone super attractive according to modern-day beauty standards. So a lot of makeup, even clothing, hairstyles. It’ll pull from historical resources, but it’ll adopt a 21st-century or 20th-century view on beauty. Skin is flawless, eyebrows are filled in, everything is very clean.

It does also reveal historical biases against specific marginalized groups. One example that I came across with Claude for the homestead game, I wanted to have definitions of terms that players would be able to click on if you don’t know the Civil War or treaties. All these different terms, little snippets of information that I would over-explain, but I asked Claude to give it a shot. And Claude, for his definition of Indigenous peoples, used past-tense language. Of course, you have to have that conversation and say “No.” Indigenous peoples have long enduring legacies and rich cultures that operate outside of and against settler colonialism. But Claude is pulling from historical sources that reaffirm biases against Indigenous peoples. So again, you have to step back and think critically about history, who’s writing it, who has the power, what’s being preserved, and fact-check and be mindful of what AI is drawing from, what it knows and what it’s able to accomplish reasonably.

Mike: That’s a very good reminder. Let’s hear from Alex Goldmark, executive producer of NPR’s Planet Money and The Indicator. Alex, you’ve done quite a bit with generative AI and AI tools, both through your Knight fellowship and your work at NPR. What are some ways you’ve used it for your work with Planet Money?

Alex Goldmark: The thing that I did while I was at Stanford last year, as ChatGPT became the big talking point of Silicon Valley, was related to Planet Money. We tried to think about all of the errors and the biases that Lauren has been laying out. Could we make a chatbot that would be useful for journalism and help a listener of, say, Planet Money or any local news station engage with the archives, but in a journalistic way? If you could constrain your searches to just a reliable source, in our case the archives of Planet Money, or in many of your cases, it would be your station archives, Would the answers be more reliable? Would they have less or different biases? Could you have it cite the source material? Which currently, I think, is a big problem with these tools. They don’t site their sources, which is an existential problem for journalism, but another conversation for another Zoom. Could we build that and also have it be humble and admit when it doesn’t know something? Right now, these tools will often just make up an answer as best it can, and sometimes they’re good and sometimes it’s bad, but you can’t really tell, unless you use it a lot, whether you’re getting the good or the bad version of the answer.

We wanted to know if we could build that in. So, we built it. I worked with a computational journalism class on campus and Steve Henn, a former NPR tech correspondent who is now working with Stanford on some entrepreneurial journalism work. Some students from this class helped us. So you can go and test it out at planetmoneybot.com to see what I’m talking about. You ask it a question, and it searches the archives of Planet Money to answer your economic question. And hopefully if you ask it a question about, like, how to make a sandwich, it says “I don’t know,” unless we’ve actually covered making a sandwich on the show.

The more useful part of how we use it day to day is that we often have to figure out what we’ve covered before. It’s a huge archive going back decades. And new staff don’t know, or they don’t know what an economic term means. So I would try to search in our own archives before I searched somewhere else to see how we’ve covered it, how we’ve described it, what was our take on the minimum wage and whether it does or does not kill jobs or something like that. These kind of contentious topics where you want an answer from a trusted source. So it’s been useful for that.

This is a proprietary built tool just for us. It’s public, but I recognize that doesn’t help everybody else here to search their archives. Though if somebody else wants it built, I think it’s not that hard, and Steve, who I worked with, would be happy to help you build it.

What that really did was help me understand deeply how these tools work. So now I’ve switched to using Claude, which I also recommend more than ChatGPT for the sake of journalism because it is more specific and more grounded, as far as I can tell. It’s slightly more reliable sourcing. Where do you actually try this? Poe.com. That is a one-stop shop that lets you — without a login or maybe without paying, you might have to give it your email — try ChatGPT, Claude, DALL-E, image ones, text ones, all in one little place. You just pick a different button and you can try any of them with a way less intimidating interface.

I turn to [AI] for reverse search, is what I call it. I think of AI as a tool. It’s just a tool like Google. I don’t expect it to be magic. I know it’s going to be good at some things and bad at others, and I need to learn how to use it to have it serve my purposes better. At Planet Money, I’m often going, “Oh, there’s an affordability crisis, and I want to cover housing, but I don’t actually know the economic terms that economists might use for that.” I might type in what our story is or what our character is going through and say, “What are the economic concepts that have been studied by academics here?” It’s very good at coming back at you with, “Here is the term for that. Here’s the jargon that you didn’t know to go look up,” which then lets me go and find the research or find the researcher.

An example of that was a host was going, “I want to do a show in which we share economic concepts … that have not spread that might help society in a way.” OK, I can think of a few, but I think I asked Claude, “What are some lesser-known concepts?” It gave me a list of 10. I said, “Those aren’t what I’m looking for. How about ones that help the world and maybe have some counterintuitive thinking?” It gave me another list. After four or five different types of prompts, I had a great list that I gave to our reporter to track down and use for interviews. That took me, I don’t know, 10 minutes, whereas the Googling version would have taken several hours. And more phone calls, right? So it elevates us to get to a smarter question with a source quicker by knowing how to speak their language, by getting their jargon. And then we take out the jargon before we publish, but that’s what we use it for.

This is a bit more advanced, but it’s I think a thing we might all consider that we might be doing in six months or so. I tried to create a research assistant for myself. Open AI now allows you to make what they call custom GPTs through the ChatGPT website. Claude doesn’t have it yet, but I bet it will come to Claude soon. You can give it instructions. You can say, “I’m going to give you a document, and then you do certain things to that document.” I wanted it to be able to take research papers for me and then summarize them, but according to my definition of newsworthiness. I wanted to say, “Is this confirming or contradicting consensus in the field of economics, so to speak. Take a wild stab at it. Machine, do you think this will be newsworthy?”

It guesses, not really right, but it’s a little better when I have 20 new papers that I might want to read through. Which ones should I then focus on? And the abstracts are just notoriously terrible. I assume many of you who have beats that cover academic fields find that the abstracts don’t often tell you whether you should read the paper or not. I just wanted a thing to tell me, should I read the paper or not?

This didn’t work very well, I’m just gonna confess. It was too vague to give me my answers, and I ended up one by one uploading the papers to Claude through Poe.com. And that was an excellent summary of papers. That, I would endorse. If you have 10 research papers that you’re trying to get through or something that’s just very long and you don’t quite know what to do, which one to focus on, upload them to Claude one by one and tell it what kind of summary you want. I said something like, “I want a two-sentence summary of what this is about. I’d like you to tell me what the findings are in about 50 words or so and if they are significant and if they have broad societal impact. And then I’d like a longer bulleted summary that includes the methodology. Roughly, in plain English, how they came to their conclusions and what their conclusions are.” Then I said, “Explain the math to me as though I am a high-school student, and explain the economics to me as though I have a deep understanding of the field” and blah blah blah. If it comes back and I’m still confused, I change that a little. But I put in that much information in my request when I’m asking it to summarize something, and then you get back something pretty close to what you want.

ChatGPT was terrible. It seems to have guardrails where it doesn’t want to give you details for some reason. I assume it’s their response to being criticized for so much of the terrible things that it used to spit out. But Claude seems more confident in summarizing academic work or government reports or things like that. I think you could also put in city council minutes. This is what Dustin Dwyer is doing at Michigan Radio. He’s got a version of that. So I think summary would be a great help.

I can go on about the dreams of things I want to try to use next, but I’ll stop there and say, play around with the Planet Money bot and see if it’s exciting and if you think it might be useful where you are. I would love feedback on that. If anybody thinks you could see a good use for it at your station, I’d love to spread it and be helpful. Right now, it’s just a research project. It’s just a learning experiment.

Mike: Sign me up for a Current bot.

Alex: Yeah, let’s do it. Search is really hard, right? Search is bad, and it’s very hard to find something. It’s especially hard for podcasts. This actually is better at understanding when you’re trying to get a concept, when you’re trying to search for a rough idea, or you can type in something like “I’m thinking of buying a house. Which are the episodes I should listen to?” Google doesn’t do a good search for that. Or “I’m going through a breakup. Which episodes might help me feel better?” It is actually able to understand that kind of request, which Google does not. So I can imagine it being helpful.

Mike: That’s a lot of great advice for people to digest. Thank you very much. Let’s move on to Mikey Centrella from PBS. Mikey, one way that you said you use generative AI is to learn about new concepts and ideas that you encounter. How do you go about doing that?

Mikey Centrella: Great question, Mike. Alex and the other panelists did talk about how GPTs are really wonderful for summarization. Find everything on a topic. Replicate those ideas or write new variations of it, summarize it for me and help me adapt it. Like a research assistant, is what Alex was talking about. So if I’m doing a platform analysis, like, for example, what’s on SVOD [Streaming Video on Demand], I might prompt ChatGPT. I like to use ChatGPT-3.5, personally. We use Plus at PBS, but when I’m just hanging out at home and I’m researching, I’ll just pull up my mobile phone and search on GPT-3.5, and it’s good enough. So, for example, “Provide the top 10 analytics companies for connected TVs on SVOD.” And it will summarize that for those top 10 companies for me so that I don’t have to do the Google search and do it myself and analyze everything on my own.

Or if it’s a concept — along that same sort of thread, uncovering what I learned about the concept of automated content retrieval, or ACR, and in the context of TV, what does that mean? I don’t really know, and I wanted to learn more about it. So I used ChatGPT-3.5 to help me understand more about a concept so that I can dive a little bit deeper after I get the gist of it, because it does a really great job with summarization. You can look all across the internet, read all the articles and give me just enough information for me to dive a little bit deeper. So it’s good at gathering that knowledge, good at summarizing it, and good at telling me what I need to know to take it to a step further.

It also helps with ideation. I use ChatGPT-3.5 a lot for coming up with different ideas or thinking about things in a different way. For example, I’m writing a blog right now for PBS and wanted to title the blog series something interesting. I asked ChatGPT-3,5 to assume the role of someone who works at a media company writing a new blog for emerging technology and to give me 10 different possible titles. And here are three: “Beyond Screens,” “Breaking Bytes” or “Future Frames.” They’re all pretty good. I could work with that, and that’s a good idea that started to get things going.

So that’s how I’ve used ChatGPT primarily personally. But as a team, we use a lot of different tools to help out with research, but more as we try to implement things on an infrastructure basis for PBS and for the member stations at large.

Mike: That’s really great to hear those. I’ve used it for things like headlines, social media copy, that kind of thing. I don’t usually use something wholesale. Usually you tweak it or it gives you an idea and you move in another direction, but it can be really good to get those creative juices flowing.

One thing you’ve talked about, and you actually dealt with this in the guide that we published today on Current — you contributed a section about using AI tools to help with coding. What are some of the ways that you and your team have leaned on generative AI to help you with that?

Mikey: Code assistants are really, really helpful, to be quite honest, but they can also get in the way. GitHub Copilot, or Microsoft Copilot, is by far the one that has been the most used. It’s sourced on from GitHub, which is where a lot of open-source code is posted, and so because it’s a larger pool, it probably has a more accurate and bigger database for it to search from. Developers that I work with, including myself, we do use GitHub Copilot a little bit for checks and balances to make sure we’re not forgetting anything or it’s helping us. But that can also be a little bit annoying, in the sense that it can kind of get in the way of someone who’s actively trying to write something. If something is incorrect or doesn’t quite fit in with the way we structure things internally at PBS, that can be more challenging and create more time than actually being helpful.

Amazon’s got CodeWhisperer, which is very similar to GitHub Copilot, but the main difference being that it’s been trained on AWS [Amazon Web Services] code in addition to everything on GitHub Copilot, and it works very well with AWS products. So if you are in the AWS infrastructure cloud, the Amazon Whisperer is really wonderful to use because it knows about some of the other tools and the other APIs and it can help you do things in sort of a multistep process as opposed to just breaking it up.

ChatGPT and Google Bard also have the ability to offer code enhancement. I think Bard is probably a little bit better. ChatGPT Plus is good, but we have found that it’s good for just learning … the basics of Python, not actually writing code or checking code, because a lot of times ChatGPT, which is trained on Stack Overflow documents, can be a little bit more inaccurate. … You have to spoon-feed it. You can’t give it a whole long list of code, many lines of code. You can only give it certain bits at a time. So therefore it’s not as functional.

So to summarize, GitHub Copilot is the best of them all. You have to pay for it. Amazon CodeWhisperer is free and really great if you’re using AWS tools. Bard is very expensive. So if you’ve got the budget, cool, but be careful with that one. And then ChatGPT, if you want to just learn [with a] coach or a teacher, that’s probably a good one to look at as well.

Mike: Current published a piece by Alex Fregger at High Plains Public Radio, who talked about how he was trying to find a way to automate production of promos at his station. He thought there was some way that he could save hours of time that he was sinking into it. It was just very repetitive and doing the same thing over and over. And he didn’t have much coding skills but he used AI to say, “I want to do this. How do I do it?” And it led him through the process, and he was able to do it on his own. So it can really be a great way for people who don’t have much knowledge to quickly level up and do some things that previously would have been out of reach.

You are also very enthusiastic about using AI tools for design and images. What are some of the best tools you’ve used and what do you do with them?

Mikey: I personally believe that the best tool in the marketplace is Adobe Firefly. If you haven’t used generative fill in Photoshop or if you’re not a Photoshop user, I would recommend it wholeheartedly. But the reason why I believe it’s the best is because Haresh Parekh [Adobe’s Director/Principal Scientist of Data Intelligence Services, GenAI Feedback, Growth Platforms] set up an infrastructure for training Firefly in a different way. You may have heard the phrase “garbage in, garbage out” as it relates to data. And instead of even thinking in that way, where you have clean data in and clean data out, they created a whole taxonomy infrastructure structure and model from the bottom up. They basically rethought everything, and of course they trained with appropriate images, but they created a six-step architecture so that their AI models could really cleanly deliver what needs to be delivered. So with the case of generative fill, when you are using that to enhance an image or to create something new from an image, it seems like magic because it’s so incredible. So that’s probably my favorite.

I know some other designers that we work with at PBS, we use Figma a lot. … It’s basically a cloud-based Photoshop tool, but it has a feedback wizard which allows AI to give you suggestions for UX and UI. It can give you some features ideas and a features matrix. And we do a lot of testing with other tools, too, like Midjourney and DALL-E. But for me personally, I would say Adobe is leading the charge here in showcasing the right way to set up image generation through a data infrastructure. We’ve got some ideas on what we can do with these tools, but right now I just want to be clear that we’re just mostly experimenting.

Mike: This has been a great conversation with lots of great advice to act on. We just want to make sure that we have time to answer some questions from the audience. So I’m going to kick things over to Chad, and he’s going throw out some of the questions from folks in the chat.

Chad Davis: Brandy Miller said there’s a lot of backlash online for using AI and questions about the morality of its use. How do you address these concerns with your audience? Do you have a plan for addressing copyright issues? For example, AI tools pulling content from copyrighted work. I know Mikey mentioned Firefly, which does indemnify its users because they’ll be trained on the library of photos it has. Thoughts on that?

Ernesto: Especially with dealing with audience concerns being here as a station, I can tell you a lot of times audiences bring up issues not just about the issue, but because they want assurances that we take our place of trust seriously, that we hear their concerns and that we are endeavoring our best to navigate those carefully. … So especially when you’re talking about these things for the audiences, it’s really critical to hear out those things and also just make sure you are regularly validating and explaining the processes for which you begin to do this kind of work, but also the policies you put in place. That means it’s really important that every organization have these policies not just around content, and I’ll be writing about this very soon, but how it influences the rest of the organization. If you’ve got, say, operations people, HR people, development, other folks who are using AI for other kinds of things, and you don’t have policies on that, your organization probably wants to have a conversation about it. Because, to the points that Lauren brought up a little bit earlier, there have been biases identified in these models. And if we’re sourcing those bits of information that different parts of the house are going to be using, we really need to have some very set policies around that so we can then articulate out to our audiences, so they have assurances that they know that we’re being very, very careful about it and we take their trust very seriously.

Mikey: I just wanna add one little nuance to that, which is we’re talking largely about the free tools or the tools that are easily accessible, and those ones probably have more concern about how they were trained. But if you do want to embark on an enterprise platform and actually pay money to get some of these tools and look at them in a way that can be utilized with your own data, let’s say through AWS, it’s essentially a walled garden. So any data that you put into it, it can’t be trained against something else or it can’t be given to another company to be trained with, and any data that it’s sourcing to you has been trained from a very controlled subset. So if that is a huge concern, I would highly recommend taking a look at enterprise platforms and pursuing the relationship with some of the vendors that might be able to offer you that approach to a walled garden so that you can protect the copyright within a sandbox.

Chad: Julie from Current says, “I’m curious about what the panelists believe are best practices, especially if you have a news organization around transparency. Should all images generated by DALL-E be labeled? Should all posts assisted by generative AI tools be marked as ‘generative AI contributed to this article’? Surely we don’t need to reveal that AI provided a transcript, but there may be many other examples of uses that raise questions and concerns.” Any thoughts?

Alex: I agree. We need to be clear, to Ernesto’s point. It’s speaking to the trust more than it’s actually speaking to the facts of a given case, and I actually believe the better path is, just avoid anything that you would feel you need to disclose because it might be problematic. Ban everyone that you’re working with from taking text directly from any of these and putting it directly to the public. Just don’t do that. Say it’s not allowed because it may not be reliable and it wasn’t created by a human. So that instead of saying we did this, you say, “We always have humans tell you the news.” And then you can just stand by that — that there will be no synthetic voices, that there will be no auto-generated copy.

It’s a little different for touch-ups of photos, and there’s obviously going to be a sliding scale of what’s counted as generated. What if it’s a headline? What if it’s the alt text of a photo? Those are going to be the interesting ethics cases. But I would believe that whatever you’re having created that the audience touches that was created by AI [and] that wasn’t edited, adjusted, changed by a human should say what it was created by and have a link to some longer post about the process by which that was created. Otherwise we are misleading people. It seems like a clear case of just don’t do the thing that you would have to disclose because it might be bad if you did it. Just don’t do it. That’s how you avoid it.

Ernesto: Plus one to everything Alex just said. Here at KQED, we’ve done our best to set policies around these things and we have particular restrictions around it, but also just making sure you disclose to the audience … just as a trust issue, just letting people know this is where it’s coming from. You can certainly explain a little bit why and how this helps you to put resources in other places. But, most of the time … people just want assurances that we’re being transparent, and that’s the biggest part of it.

Chad: Excellent. I will just opine real fast, because we actually do have a generative AI policy at Nebraska Public Media, and we make a distinction between corporate content like press releases and items like that, and editorial content. And that’s a whole deeper dive itself, but there are ways to think about this when you’re thinking about your own organization’s policies that are probably worth considering.

Next one, Suzanne Smith. “Has anyone tried to put SEO best practices into something like Claude? I know there was some discussion in the chat with some SEO folks, but … has anyone really played with generative AI tools and SEO?”

Ernesto: I have taken a lot of copy and pasted it in — again, Claude’s a good example because you [can] put a lot of text in there — and prompted to say, based on what you understand of current algorithm models, does this adhere to SEO best practices, or where are improvements I could make to increase my search engine optimization? It’s a lot of work to do per article. So I don’t know if you want to do it for everything in your organization. And there are plenty of WordPress plugins and such that will do these things for you that are not explicitly AI, but in a lot of ways you could certainly use if you’re trying to do it writ large for all your content for your organization. There are a lot of these models. ChatGPT being a good example. Bard does this as well. You can just ask it, can you just compare it to what you know of how Google’s rankings work? Where can I improve this copy?

Mike: There’s a Slack AI-powered plugin called Yeseo that is really helpful for suggesting headlines, suggesting keywords, that kind of thing. So if you use Slack, I’m sure many do, you might want to give that a try. It’s handy because if you’re on a team you can have other people check out what you’re doing and weigh in with their ideas. We’ve used it some at Current and it’s pretty helpful.

Mikey: There was another one that I was gonna recommend — thanks, Mike, for that one — but it’s called Keywords Everywhere, a Google Chrome browser extension and has its own platform, but that one’s good for SEO. We’ve experimented with it a little bit.

Chad: There’s one question I wanted to just pull in because I think it’s super important. Alexis Richardson asked, “Can anyone speak to the use of AI and accessibility at their stations?” I asked for a little bit of clarification from Alexis. And what they’re looking for is information on how generative AI can be used to increase inclusivity or enhance inclusion.

Ernesto: This is definitely a spot-check kind of conversation. You can certainly apply this to lots of content. But also, go to your persona — who are trying to speak to around an initiative or piece of content or a letter or whatever it is? What is your objective to getting that person to reply to it, and then what are the parameters beyond that? And then just stress test that a little bit. None of that is ever going to replace bringing together a small focus group or talking individually with people and doing a design-thinking exercise, so to speak. You could even use a design-thinking exercise almost as a prompt. What is this persona? What kinds of questions are they looking for? How would this bit of information solve it? And ask a GPT model to figure out, is this really applicable or not? Does it make people feel like they belong? Does this feel inclusive? You obviously want to talk to people about those things individually and get at least their anecdotal feedback on these conversations, but it’s just a little stress test to begin to figure out how can we make this a little bit stronger, make it a little bit better. It’s just one more input beyond the community inputs that many organizations already are taking.

Alex: I have a question on accessibility. I hate to kick it back to you, Ernesto, with the question but it’s a thing I’m thinking about and wondering about. Yes, it would help for creating alt text for images and making different or better transcripts more easily depending on how you’re already doing it. I think it can be useful for all of those. I was wondering about language accessibility, and I have wondered about the trade-offs and was talking to some folks at stations who have stuff that’s in English and they want to reach the Spanish-language speakers of their area. And they don’t have the resources to do translation at scale. So, this trade-off of, when is it better to have it machine translated and therefore probably with some error and missing nuance in potentially problematic ways, versus not having it at all. And how do you think about when you might pull that trigger or what guardrail you can put on it. It’s a balance, right, of reach and of introducing potential error or imperfection.

Ernesto: Alex, that’s a brilliant question because it made me think about a couple of different things. I think the biggest part of this for every organization when we’re talking about accessibility and inclusion is thinking about what it means to connect with and serve those audiences to your organization. And what I mean by that is, what is the spectrum in which you’re hoping to connect with people? For example, for some folks just based on your capacity, it may just be we want to provide information. So maybe it is we want to translate something that’s on our website, maybe some news stories or a series of new stories. Well, some of the tools that we talked about can do that. You’ll certainly want to have at least a worker or a staff person who is brought in to look over those things to catch the cultural nuances. But it’s something you can certainly do in the models we talked about can do that.

And if there are other things, like you want to make part of your effort to connect with people and serve them making them feel like they’re included in social and other kinds of things, there are some of the things that Lauren talked about in terms of images. something like Pika does a video that can be translated into English and Spanish. There’s some of the image translation tools. There’s tools like Copymatic that will make an AI script for LinkedIn, for Twitter, for Instagram, for TikTok in Spanish, if you want to do that.

However, if you’re wanting to do fuller engagement, that’s probably a longer game for a lot of organizations. You want to maybe think about how long that is for you. And what I mean by that is, so, OK, say you’ve done those other things that I’ve just mentioned. You’ve done some social things. You’ve translated some articles and such. So, what happens when somebody who’s seen your articles online or has seen some of your social media shows up to your office and speaks Spanish and it’s a story that your building should be covering. Can someone talk to them and really have a conversation with them about what that story is and make them feel like they are welcome to your building? What if they show up at your events? How do you connect with those folks?

There are a lot of organizations that are looking at the long game here. I can think of like at WVIA, Vicki Austin over there, Maria O’Mara over at KUER, they’re getting ready to launch a full Spanish-language bilingual radio station. Lowell Robinson here at KQED is thinking about some of these things as well. He shared some of our examples in the chat. But that’s something you may want to think about in terms of how you really connect with those audiences.

There are a lot of great tools to connect with people in terms of just sharing out the articles. But you should also be thinking about what happens if they start to engage more with you. How do you welcome them in, and what’s your runway or your funnel? Much like you would think about fundraising: content, development, engagement, other kinds of work that you would do in the community.

Chad: Shaun Townley says, “Some unsolicited advice based on our experience — if you have a community advisory board, I’d recommend speaking to that community advisory board or to your CAB members about generative AI. It can really help us get our heads around our audience’s level of understanding of these technologies and their expectations.”

I very much liked that that sentiment. Those of us who are working in emerging media are very much inside this generated AI bubble on it. It’s sometimes a little bit bracing when you come out of it and you realize where this sort of average information consumer is out there in the world. So I think that’s great advice.

Glenn Richards said, “Has Adobe Enhance been mentioned yet? Amazing when you have off-mic sound from a commission meeting, et cetera.” I don’t know much about it. I like Adobe’s suite of tools. I don’t know if anyone else has used it. Ernesto, if you want to speak to any of that at all.

Ernesto: I love Enhance. It is really an interesting tool where you can have audio cleaned up. You can do a bit of editing here and there. I think that there’s still a free tier. Somebody’s going to correct me in the chat, I hope. But if you just want to try it, particularly if you’re doing a lot of those field recordings that sometimes it’s just a little messy when you get it back, and no matter how good the mic is, it’s definitely something that makes it a little bit more air-worthy, among other things. There are a lot of different uses for it.

Alex: But then do you disclose that it was cleaned up by AI. That’s the other question there.

Ernesto: I would. But I’m definitely all about oversharing. I grew up in Texas. We overshare.

Chad: David asks if anyone is using generative AI for video. That is a frontier for certain. Anyone on the panel dabbled in generative AI for video?

Mikey: Yes, we’re experimenting with a couple different applications of how to use it for video. So first off, generative AI has a lot of different subsets of what it could do. Recognition is one of those things — looking at images and pulling out faces. Same goes for video, moving images. So we could use it as a way to help screen content, if you will, to make sure that there’s nothing in that content that might be flagged for something that’s not appropriate for our audiences. And so that is one way we’re looking at using generative AI for video.

We’re also looking at ways we might be able to enhance the video in a certain way that could be pleasing to a user to do something fun and promotional, perhaps insert yourself in the background of one of our popular drama shows. We’re seeing what type of technologies exist right now to do that and if we can do that with our own IP and licensing. And, we’re also trying to think about if there’s ways to make shorter clips from longer form and to use generative AI. In the same way AI can summarize text, it can do the same thing from a transcript of a video. So when you watch some of the other platforms and there’s a recap from season one or a recap from the previous episode, is there a way that generative AI could do this? Could it not only take the video clips, but also summarize the text to help us create what we’re calling “dynamic recap”?

Those are the three ways we’re looking at generative AI for video at the moment. But those are more technical ways that we might be able to enhance our audience’s needs as it relates to viewing. It’s not necessarily about using generative AI to create video per se, but certainly ways that it can be used to help us deliver better video experiences.