Peter Breslow on his start at NPR: ‘This was what I wanted to do for a living’

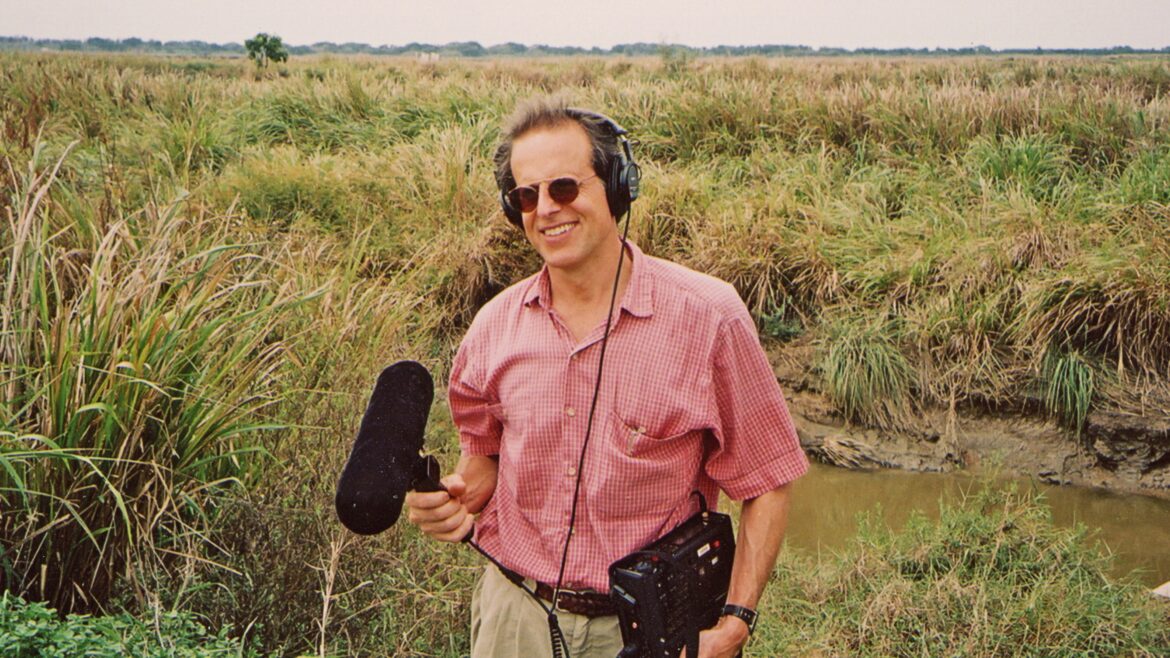

Peter Breslow in coastal Ecuador, 2001.

In a new memoir, Peter Breslow looks back on his career of almost 40 years as a producer with NPR. Outtakes: Stumbling Around the World for NPR follows Breslow from his earliest days slicing tape and chasing stories to his travels reporting from locations such as Baghdad, Mt. Everest and the South Pole. In the following excerpt, the book’s first chapter, he recounts how he landed a job with the network — and kept it despite the occasional humbling broadcast snafu.

It’s an initial round in my tryout for a production assistant position at All Things Considered (ATC). We are writing scripts on typewriters, so copy changes are laborious. I’m working on an introduction to a piece for host Susan Stamberg to read. In these first days I don’t own a watch, however, and I lose track of the time. All of a sudden, the producer is yelling. “Get that into the studio now!”

“But, but . . . the intro needs to be re-written.”

“Now!”

I burst into the studio and run up to Susan sitting at the microphone.

She is an icon. A radio goddess. The first woman to anchor a national nightly news program. And like so many women during NPR’s early days, she is tall. (Oddly, a number of the NPR men back then are pretty short.) I am bupkis—less than chopped liver.

As the seconds tick off on the countdown clock for the story that is currently playing, I try to explain to Susan how the intro should go. The information is all there, but the paragraphs need rearranging. I provided arrows. “Okay, Susan, you start here. Then go to the bottom paragraph, then back to the middle . . .”

:03 . . . :02 . . . :01

Susan’s mic is opened. I shut up. She starts to read. Good, good. That’s right. Then she stops. She’s lost her place in the mess of arrows I’ve drawn on the script. Dead air, dead air, dead air. Then she figures out my chicken scratches, finishes reading the intro; her mic closes; the piece airs. The consummate pro.

I had had a similar situation with another host a few days before that.

His reaction: “If you can’t make your fucking deadline, get someone in here who fucking can!”

Susan is exacting and a force of nature but also forgiving of a radio rookie. All she says is: “Honey, you need to get yourself a watch.” It’s the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

At first, I can only watch and learn as we sit in an edit booth listening to reel-to-reel tape, Susan smoking a cigarette and saying, “Yes, THAT’S the tape cut we need.” She always knows her vision for a piece, but as time passes (and Susan quits smoking), she starts to trust my suggestions too. Sometimes, though, she’ll say my idea for a transitional scene in a story is lame, and then I’ll give her shit about the half-ass way she holds her microphone. She’s one of the few people at NPR who calls me Pete.

Over the decades we have interviewed countless artists, authors and musicians, and worked together around the country and the world, from Kenya to Russia to Lithuania—all sorts of places. We even ended up living across the street from each other for many years, with Susan acting like an aunt to my twin daughters Eden and Danielle, looking on as they blossomed from babies into young women.

That script-crashing moment in the studio with Susan came at about week three or four of my NPR audition. And I almost didn’t even make it that far.

I had decided to pursue a career at NPR after two years drifting around South America. Returning to the U.S., I was unemployed, with few marketable skills and no real notion of what I wanted to do with my life.

Unlike some of my future NPR colleagues, I wasn’t a radiohead growing up—aside from listening to baseball games, The Beatles, storyteller Jean Shepherd, or the occasional heavyweight fight on my transistor radio under my pillow at bedtime.

My recording experience back then consisted of going over to my classmate Kenny Greenfield’s house Saturday afternoons in seventh grade and cracking each other up taping absurd stories we ad-libbed into his father’s Dictaphone. Years later I’d managed a degree in English and liked to write, but had never taken a journalism class. However, I had started listening to National Public Radio, and this seemed like something I might give a try. It would become my journalism grad school.

I had little to offer the place, so I figured I would write a gonzo cover letter (this was pre-email) highlighting my wandering in South America and the fact that I was an Eagle Scout. My inquiries to the network were answered with form letters from everyone except the executive producer of ATC at the time, Steven Reiner, who liked my travel and language experience (Spanish and Portuguese), as well as my saucy sense of humor.

He invited me down to D.C. to try out. This was a time when you could still sweet talk your way in the door at the organization. Today, they would have never let me out of the elevator. Our entry-level producers are scary smart and over-qualified. But in those years, NPR was small and fledgling and better suited for taking a risk on someone like me. I was terrified.

When I arrived in February, the city was frozen solid by an ice storm; and as this was the time of Mayor Marion Barry, whose approach to snowy streets was to tell residents to wait for spring, public transport was at a standstill. So, I hitchhiked to the office.

When I got to the building, I discovered that Reiner was on vacation in Brazil, and he had not alerted anyone that I was coming. After some negotiating (“Who did you say you are?”), they cautiously let me inside.

My second day trying out, an ice-encrusted Air Florida Flight 90 crashed during takeoff into the 14th Street Bridge and sank to the bottom of the frozen Potomac River, killing 78 people, 74 on board the plane and four on the bridge. Five people on the plane survived. The newsroom exploded. Editors, reporters and producers raced around making phone calls, writing copy, interviewing witnesses. It was an awful event but hugely intoxicating. As I tried to make myself useful, I knew then and there that this was what I wanted to do for a living.

As I’ve mentioned, I just barely made it through those initial days without getting tossed out with the recycling. (Actually, I don’t think they even had recycling that far back.) At the time of my NPR audition, I had never edited audio tape, so I drenched myself in the process as intensely as I could. By the end of that first week, they decided to roll the dice and let me edit a simple phone interview.

I spent the entire day cutting this thing, amassing a tall stack of 10” silver aluminum reels in my edit booth full of outtakes—identical reels that I had neglected to label. I think you can see where this is headed.

As my deadline approached, I suddenly realized that I had completely lost track of which was the master reel with the body of the interview. With five minutes to air, the show producer poked his head into my edit booth.

“Everything okay?”

“Yup, just finishing up.”

Well, I thought, I guess I’m not getting this job. But then for the first of what would become many times, the radio gods smiled upon me. I somehow fished the master reel out of the morass and handed it to the producer as he screamed into my edit booth with a minute to air. I have no idea what it sounded like, but the interview made it to broadcast and dead air was avoided.

On another day during my tryout time, I was standing in an editor’s office waiting for an opportunity to pitch a story idea just as she was asking the reporter in front of me if he would be available that evening to cover a memorial service. It was for Oscar Romero, the El Salvadoran archbishop who had been assassinated while serving mass in San Salvador two years earlier.

The reporter said he couldn’t. Then she turned to me, someone she had never met. “How about you? Can you cover this?” Not only had I never reported an NPR story before, but it would be a fairly quick turnaround for a neophyte—the next morning. Of course, I said, “Sure.”

That night I followed the crowd that sang and chanted during their candlelight march through the streets and then recorded speakers in a downtown D.C. church as they eulogized Romero, recounting his activism and heroism in the face of right-wing death squads. Then I rushed back to NPR to start writing my piece.

It would have taken an experienced reporter a couple of hours to put this thing together. It took me all night. My five a.m. deadline seemed so far away when I started the process, but as the evening wore on, it came creeping closer and closer, like a tiger sniffing out prey.

People on the Morning Edition staff were very kind and helped me select my audio cuts (we call them actualities or acts) and coached me on my voicing. In the end, the piece made it to air; and I learned that when push came to shove, I could turn around a story on deadline. It was a big confidence boost.

Despite my deadline fiascos, NPR was foolish enough to hire me. I kept filling in, and I think at some point people just assumed I had a job at the place, so they gave me an employee ID. To this day, I’m still waiting for an administrative person to discover some misplaced yellowed paperwork and come tell me, “You know what, you are not actually employed here, never have been.”

And with the job came an instant love of making radio:

- It was creative. The rules were few as long as the story worked.

- It was cheap. You could do it with a simple tape recorder and microphone.

- It was low profile. You could work all by yourself. You didn’t need the whole crew of people television required.

- It was intimate. You were whispering right into someone’s ear.

- It was non-intrusive and didn’t demand the listener’s complete attention. They could drive to Poughkeepsie, make linguini with clam sauce or unclog the upstairs toilet while tuning in.