Samuel C. O. Holt, author of seminal study on public radio, dies at 87

Katharine Holt

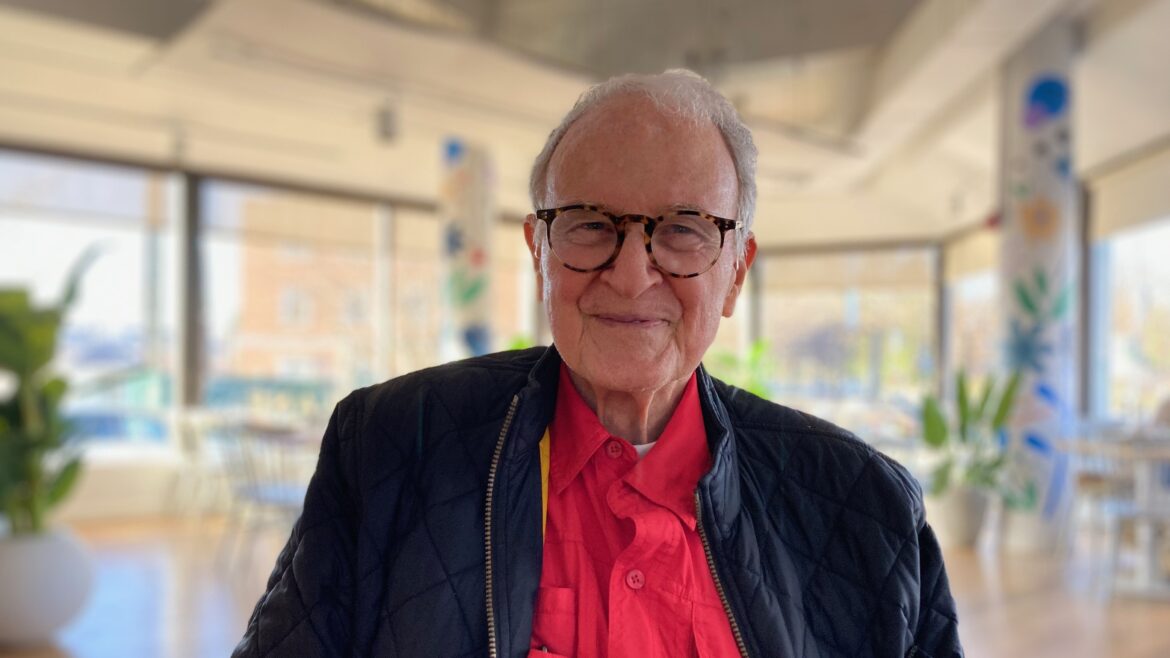

Holt in December 2022.

Samuel C. O. Holt, a researcher and programmer who helped lay the foundation for NPR and PBS’ national program services, died Oct. 11 at age 87.

As a Rhodes Scholar who had earned a graduate degree from Harvard, Holt wrote the pivotal 1969 Public Radio Study that provided a framework for building the public radio system as it exists today. His recommendations included allocating a portion of the FM band for noncommercial stations and creating NPR. He went on to help build support for creating PBS’ National Program Service and later worked at NPR as a senior program executive.

Public radio “might not have been if the Public Radio Study had not been done,” said Bill Kling, founder and former president of MPR and APM. Holt hired Kling to visit public radio stations across the country to help inform the study.

“He was very smart,” Kling said. “He quietly understood where the broadcasting system could go — way before others did. And he gave it everything he had in terms of enabling it to succeed.”

During his graduate studies at Harvard, Holt worked with Hartford Gunn, president of WGBH in Boston who later became the founding president of PBS. That relationship opened the door for Holt to direct the Public Radio Study, according to his obituary.

‘Problems of internal organization and financing’

The study was released two years after passage of the Public Broadcasting Act. It provided a realistic look at the landscape of noncommercial radio stations and made recommendations on how to strengthen them.

“Noncommercial radio is weakened by problems of internal organization and financing within the individual licensee, and by structural and funding problems for the medium as a whole,” Holt wrote in a summary of the study. “Low budgets and other factors have made recruiting of personnel a problem for most stations. These problems complicate the job of the station manager, who is often forced to operate under the pressure of time-consuming responsibilities outside the station.”

Holt also raised questions about the purpose of public radio, according to Jack Mitchell, former director of Wisconsin Public Radio and author of Listener Supported: The Culture and History of Public Radio. Mitchell, who was the first employee hired by NPR, served on the NPR board when Holt worked at NPR as SVP for programming, a role he was in from 1977-1983.

At the time of the Public Radio Study, key decisions about CPB’s role in supporting public radio’s development were in play. Holt was grappling with big-picture questions such as, “What are we here for?” Mitchell said.

Leaders of many noncommercial stations were “very limited in their vision” and weren’t thinking about the field’s mission and future, he said.

“We were just so happy to have the money,” Mitchell said, referring to federal funding that flowed through CPB. “We’ll figure out what we’re supposed to do with it later.”

“By raising these issues and laying out the problem, that gave CPB … the foundation for going ahead with what became” NPR, Mitchell said.

‘Countervailing forces’ of PBS’ early years

When Holt joined Gunn as a founding member of PBS’ staff in 1970, his role was coordinator of programming. Public TV needed someone “who could appreciate and understand all of these countervailing forces,” said Wick Rowland, former CEO of Colorado Public Television, who worked with Holt at PBS.

Station leaders did not want to replicate the “centralized and all powerful” model of commercial TV networks, Rowland said. And PBS’ bylaws prohibited it from producing programs.

Holt, Gunn and other PBS founders were “faced with this really odd situation of creating what we won’t call a “network,” a network, without actually having all the tools of a normal network,” Rowland said.

Rowland credited Holt for understanding the competing interests of PBS’ different stakeholders. He was able to “recognize the conservatism of many of the member licensees, [and] could understand the ambitions of the producing stations,” he said. Holt also knew that “CPB was looking right over our shoulder at every decision we made. In those days, you weren’t sure whether we were really independent of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting or not.”

Holt understood that PBS had to navigate those different forces, “figure out how to make it work” and build a national program service, Rowland said.

‘A cut or two above everybody else’

Holt’s elite educational background set him apart from his public broadcasting colleagues, Mitchell said.

“Most people in public radio, at least in those days, weren’t real intellectuals,” Mitchell said. “He was sort of a cut or two above everybody else. He didn’t necessarily fit in real well with people, because he was a little intimidating, I guess would be the way to put it.”

Rowland remembers Holt as someone who was fun to work with and who had a “great sense of humor.” At the same time, he was “a hard driver, was a hard worker,” he said. “And the people who he drew around him were very much like that.”

Numerous flagship programs started under Holt’s leadership at PBS and NPR. According to a summary of his public broadcasting papers archived at the University of Maryland in College Park, these include Masterpiece Theatre and Firing Line at PBS and NPR’s Morning Edition. NPR had launched All Things Considered without any input from stations, Mitchell said.

When Holt joined NPR as SVP of programming in 1977, a constituency of station leaders “who had expectations” about program development had emerged. He was “very good at running a process that would bring the stations along,” Mitchell said.

At the time, NPR was producing other shows besides All Things Considered, but it lacked a morning news program. So Holt led “rational” discussions with station leaders about NPR’s program investments. His presentation compared the NPR programs then in production with the cost of starting and operating Morning Edition.

“The answer was obvious,” Mitchell said. Station leaders agreed to end production of other shows to free up funds for Morning Edition, he said.

After departing NPR in 1983, Holt went on to work as a consultant. As CEO of Content Technologies, Inc., he worked on the design and production of interactive media products, according to the University of Maryland archive.

Early in his career, Holt worked for CBS News in New York City as an editorial desk assistant in 1956. He joined WATV Radio in Birmingham, Ala., in 1960 as a reporter. He later became president of the station and started the first all-news/talk format in the South.

In addition to his partner Vicki Weil, Holt is survived by his daughters, Louise Elliott Holt of New Haven, Conn.; Elizabeth Burwell Holt of Brooklyn, N.Y.; and Katharine Mansfield Holt of Milton, Mass.; sons-in-law William Darman and Reif Larsen; and five grandchildren: Jane, Emma, and Edith Darman; and Holt and Max Larsen, according to his obituary.

Thank you for the excellent article about Sam Holt. He contributed so much to our profession while working with NPR and PBS. It is worth noting that his attention to public media began with his father, Thad Holt . An attorney and commercial broadcast owner in Birmingham, Holt was instrumental in founding Alabama Public television – then the first statewide network.