How public radio stations can serve deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences

AegeanBlue / iStock

A man communicates in sign language during a video call.

Two public radio stations looking to improve the accessibility of their broadcasts for the deaf and hard of hearing have found new ways to provide live captioning of their programming.

WAMU in Washington, D.C., is testing an automated speech-to-text technology developed by Enco, while KQED in San Francisco is promoting Google Chrome’s Live Caption, available since March 2021.

Enco’s technology, enCaption, is a hard-wired system that generates captions from a feed of WAMU’s live broadcasts. Its features include an automated grammatical analysis that corrects spelling for uses of “there” and “their,” for example. The text is fed onto a live captioning page on WAMU’s website.

KQED, meanwhile, simply updated its online FAQ to add an explanation of live captioning of radio broadcasts and podcasts — essentially pointing its web visitors to instructions in Chrome’s Help Center. Web users can enable the captions by changing the settings on their Chrome browsers.

KQED is trying to meet the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1, which call for captioning of all live audio content, said Carol Cicerone, manager of interactive content. Using machine learning and artificial intelligence, Chrome generates English-language captions for all media that can be accessed via the browser, including videos, podcasts and radio. The captions appear on a “hover bubble” that can be dragged around on a screen.

KQED opted to promote Live Caption because it wanted to conform to accessibility guidelines but didn’t have the resources for an outside live captioning service, Cicerone said.

“I really think that it’s just such an easy reach for so many stations, regardless of your size,” said Ernesto Aguilar, director of radio programming.

Adapting live captioning technology for radio

WAMU first tested live captioning in 2018 for its coverage of local elections. When talk show host Kojo Nnamdi interviewed a political candidate who was deaf, WAMU brought in human transcribers and sign-language interpreters to produce live captions of the broadcast. The station wanted to make the interview accessible to the deaf and hard of hearing, said Rob Bertrand, senior technology director.

Washington has a sizable population of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, he said. It is home to Gallaudet University, which specializes in bilingual education in American Sign Language and English and has an enrollment of more than 1,400 students, according to its website.

Bertrand wanted to find a way to continue serving this community by providing captions of WAMU’s signature talk programs, but he recognized that human transcription was not feasible. He looked to Enco’s enCaption and developed a customized workflow.

“We realized that we could leverage technology to reach a substantial audience in the Washington region that previously had been excluded from our content,” Bertrand said. In a given week, around 300 to 400 visitors to WAMU’s website view the captioning page, he said.

WAMU’s captions are labeled as “beta release.” That’s because Bertrand hopes to explore options for integrating the text into the audio player that appears at the bottom of WAMU’s web pages. Website visitors who want to see the captions now have to navigate to a special web page.

“We haven’t been able to start that work yet, but that is going to be the biggest difference — they will become much more prominent on our website,” Bertrand said.

TV broadcasters and cable networks have been using enCaption since 2006, according to Enco’s Bill Bennett, media solutions and accounts manager. That’s when the FCC began requiring closed captions of TV programming. Enco wants to expand into the radio market and is working to lower the costs of live radio captioning by offering a cloud-based solution, he said.

“Hopefully we’re able to accomplish this across all of radio,” Bertrand said. “But especially in markets where there is an audience that is not being served, I think those are the areas that have the greatest opportunity to add this capability.”

Though Chrome’s Live Captioning is an easy and affordable solution for stations to improve accessibility of radio and podcast programming, it has its limitations, according to KQED’s Aguilar.

Accuracy is one of them, especially in transcriptions of different voices and accents, he said. In the Bay Area, a culturally diverse region where lots of different languages and dialects are spoken, Chrome’s captions can’t reliably capture the many voices and accents heard on KQED’s programming.

Aguilar wants to see live captioning serve a diverse range of audiences by accurately transcribing the speech heard in audio programs. “I’d love to see live captioning do more of that, being able to really reflect the audience to give them a sense of place in a different kind of way,” he said.

‘Lifeline of communications’

The push to provide captioned radio for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals is not new, especially for public radio, but the focus has shifted from the early days of HD Radio.

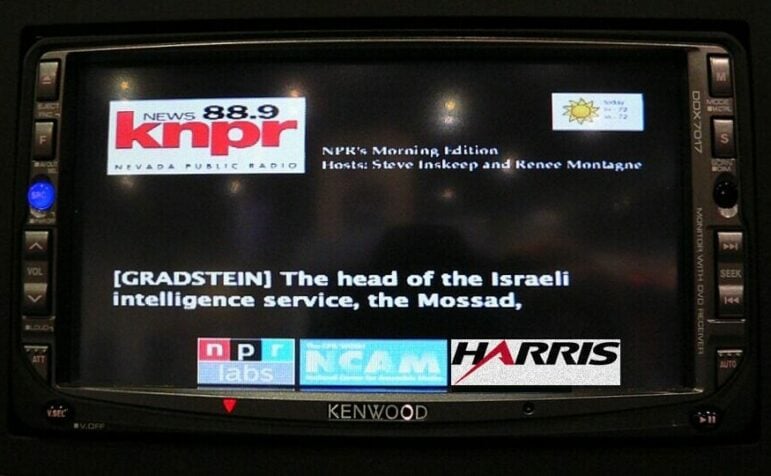

About 15 years ago, public radio explored the possibilities for captioned radio, and the text didn’t come from the internet. NPR Labs, Towson University and Harris Corporation developed a prototype of a digital radio that displayed captions on a screen.

Humans were involved in generating the captions. A voicing professional repeated what was said in a live radio broadcast into a voice recognition program, which would accurately convert the speech to text and remove background noise. The captioning data was packed into a station’s digital radio signal for display on the radio receiver.

In 2008, NPR and several stations tested the technology during events where captions of live election night coverage were displayed in various formats. Latino USA introduced captioning of its broadcasts in 2013 by joining an NPR Labs partnership.

But the prototype radio that displayed captioning was never brought to market.

While “live synchronous captioning” now is expanding access to radio content on the internet, Donna Danielewski, executive director of accessibility at GBH, said it misses the original point of radio and the earlier research. Even if digital radios with caption displays seem like “backward technology,” she still sees the need for them.

She points to public safety needs. When electrical power goes out in an emergency, deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals would not be able to access online captions of radio broadcasts. But caption-enabled radio receivers running on battery power could reliably deliver essential information, such as evacuation orders.

“Radio was sort of originally intended as uniquely key to public safety, a lifeline of communications during an emergency,” Danielewski said.

Two things would have to happen before radio captioning for deaf and hard-of-hearing people could achieve mainstream use, she said. First, equipment manufacturers would have to bring to market a display radio similar to the prototype created through the NPR Labs partnership. Standards for carriage of captioned data over radio signals would then have to be set, similar to the FCC rules for TV captioning.

“We have to think a little bit more nowadays about how to make sure we’re really reaching all those audiences in all the places they might be,” Danielewski said.