How Cokie Roberts landed at NPR: ‘They wanted her included because they loved her’

NPR

Cokie Roberts

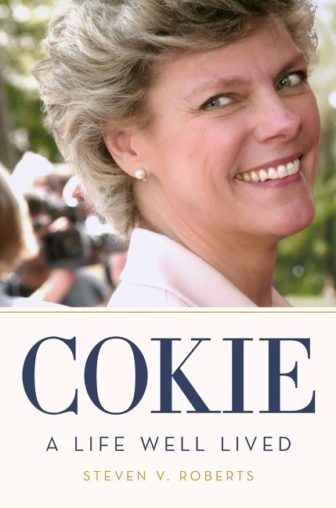

In his new book, Cokie: A Life Well Lived, journalist Steve Roberts looks back on the life and career of his wife of 53 years, Cokie Roberts. In an interview this month with NPR’s Steve Inskeep, Steve Roberts said, “This is the way I mourn. This is the way I embraced her memory.” Cokie died in 2019 of complications from breast cancer. Her husband’s book is based on dozens of interviews with friends and colleagues. In this excerpt, Steve recalls how Cokie came to work at NPR in 1978.

On my first day back in the Washington bureau [of the New York Times], I was given a desk, looked around, and saw a young woman I didn’t recognize. She said her name was Judy Miller and she used to work at National Public Radio. And I said, what’s that? NPR had been on the air for six years but we’d been in Europe for the last four, and I’d never heard of it. When Judy described it, I instinctively said, “That’s the perfect place for my wife to work. She’s crying herself to sleep every night. What do I do?” And Judy said, call Nina Totenberg — then and now the Supreme Court reporter for NPR, who became one of Cokie’s closest friends. I called Nina and she told me to get her Cokie’s résumé immediately, which I delivered the next day, meeting her on the sidewalk outside the NPR studios. It was the first time I ever saw the old girls’ network in action, with women helping one another in the way men had always done. At that memorable moment Cokie was thirty-three and had never worked a day as a full-time journalist. Nina immediately told Linda Wertheimer, who remembered Cokie from Wellesley, and started lobbying Jim Russell, then the news director. She also alerted Robert Siegel, who worked as an editor under Russell, and he had just read her piece in the Atlantic. “I had been very impressed with her article from Turkey,” he recalled. “She was insightful. She wrote well. She was a good storyteller. She was the kind of person people would open up to. She struck me as a very good fit for NPR.” Not everyone agreed, however, starting with Jim Russell. “I just felt that Cokie was not a journalist,” he says now. “She came from a very strong and historic political family. Undoubtedly, she knew politics, having been weaned on it, but my feeling was that we were looking for someone who was a journalist and I didn’t want to see us contaminate our purity. I said in a very simple fashion, this person is not a journalist. This person is a political animal. I was very monolithic in my view, and since that date I’ve always felt really silly.”

Russell reluctantly agreed to take Cokie on as a temporary employee, but getting her hired full-time required more effort. Frank Mankiewicz, then the president of NPR, was slow to come around. “At one point he tells me he didn’t want to hear anybody on the network named Cokie or Muffy or Buffy or anything like that,” recalls Siegel. “He didn’t like her name, he thought it was a preppy name and he didn’t like that idea. He had hopes for a grittier network than perhaps NPR ever became. But that’s clear in my mind, I found it very frustrating.” Her full name was Mary Martha Corinne Morrison Claiborne Boggs Roberts — her nickname came from her brother, Tommy, who couldn’t pronounce “Corinne” — and after Mankiewicz voiced his objections to Cokie, she devilishly signed off one evening with all seven of her names. At that point, Mankiewicz told the Washington Post, “I surrendered.” But in the end her distinctive name served her very well. She was the only one. And when our grandchildren were born, and folks would ask what her “grandmother name” would be, she’d answer tartly: “Cokie. Don’t you think one cutesy nickname is enough?”

Another problem was her voice. “She didn’t have a velvety female voice, she didn’t sound like a classic radio reporter, so in that sense she was not an instantly natural fit,” recalls Siegel. To make matters worse, during one job interview with NPR executives she was suffering severely from allergies. “It was one of the worst showings of oneself in a job interview that you can imagine,” says Siegel. “This was the pollen season and she was effectively in tears from an allergic reaction.” What finally made the difference were her female allies Nina and Linda, who would not give up. Robert Krulwich, who shared editing duties with Siegel, remembers that quite clearly: “I mean, it was very definitely pressure. They were for her and wanted to recruit her and were not going to back down and they were not going to give up. They wanted her included because they loved her basically, they really loved her, they were crazy about her.” When I asked Nina if sisterly solidarity had moved her to advocate for Cokie, she answered sharply: “Oh, absolutely. I wouldn’t have done that for a man. No way.” Cokie in turn embraced her new friends, telling the New York Times: “When I came in for an interview Linda and Nina were there, greeting me and encouraging me. And it just made all the difference in the world. NPR was a place I wanted to work because they were there.”

Cokie’s upset with our move back home did not end right away. “Nina got me in the door, but NPR didn’t hire me,” she recalled. “For a while I was on a weekly retainer. None of it was certain. In fact, even though I was filing stories almost daily, I wasn’t hired for a long time. Steve’s sister got married in October, and when we flew up to Boston, I cried the whole way. I couldn’t see how any of this was going to get resolved. Nobody was hiring me, we couldn’t afford to live anywhere, I felt like I was a child in my mother’s house. It was all a mess, though I loved the work itself.” It all did get resolved, partly because some of the men at NPR were also a bit “crazy” about Cokie. Krulwich kept talking about the “glow” she emitted and he recalled first meeting her years before, in the summer of 1968, at LaGuardia Airport in New York: “She was very beautiful and very pregnant, like eight months kind of pregnant. And I just remember thinking, wow, what a cool looking woman. And how lucky you were.” Siegel had first heard about her from a journalism school classmate: “I remember him talking about the beautiful Cokie Boggs, maybe she was Cokie Roberts by that time, but she made a strong impression on people in a variety of ways.”

So ironic. I remember Cokie at the PRC the year the money thing blew up on Mankiewicz, talking to station reps. She was earnestly and passionately advocating for support for her boss and NPR. The question was would we, members of the network, take on an extra assessment –– beyond our regular dues –– to stabilize NPR’s financial position. (Many stations did. Mine did.) Cokie’s lobbying was effective.

After that, Mankiewicz lost his luster but Cokie’s stature grew.

I didn’t know her personally but I always knew she was a smart reporter, a good woman.