Bob Fass, ringleader of long-running countercultural Pacifica show, dies at 87

Jon Kalish

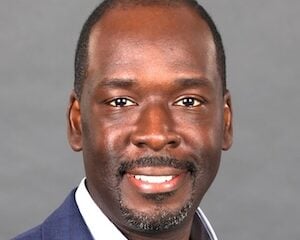

Bob Fass and his wife, Lynnie, in 2005.

Bob Fass, who presided over a late-night freeform radio program on Pacifica Radio’s WBAI-FM in New York for more than 50 years, died Saturday from congestive heart failure. He was 87.

Fass’ Radio Unnameable introduced dozens of seminal performing artists and served as a switchboard for the antiwar and civil rights movements of the 1960s. It inspired many to pursue careers in public radio and paved the way for a unique genre of live radio built around the personalities of show hosts.

“There was nothing like Bob’s program on the radio at the time,” said Larry Josephson, the last of WBAI’s surviving live radio personalities from the 1960s and ’70s. “It was often brilliant, sometimes not. It was almost always interesting.”

Before starting his radio career, Fass was a trained actor who studied at the Neighborhood Playhouse with Sanford Meisner, considered one of the greatest acting teachers of the 20th century. Fass won small parts in productions of Brendan Behan’s The Hostage and The Execution of Private Slovik. He served in the U.S. Army in the mid-1950s and, after being discharged, performed in the original off-Broadway production of The Threepenny Opera.

Fass was hired as a staff announcer at WBAI in 1963 with the assistance of Richard Elman, a high-school friend who served as public affairs director at the station. His Radio Unnameable program presented cutting-edge politics and culture served up as a mix of talk, recorded music, live in-studio performances, listener calls and just about anything else that Fass could patch into a mixing console.

The show always began with Fass’ signature greeting, “Good morning, cabal,” the “cabal” being his fellow countercultural conspirators who opposed the Vietnam War, marched for civil rights and had no problem admitting that they inhaled.

Fass was recognized as a genius at mixing records, tapes, live music, phone calls and his own raps. “We had three turntables in master control, and he would have them all going, mixing incongruous elements to produce a brilliant mix,” recalled Josephson.

Amid this juxtaposing, Fass also pioneered the art of putting several callers on the air at the same time. Regular callers provided a degree of comic relief. One referred to himself on the air as Frank Language, a reference to the warning that listeners who might be offended by certain words were advised to tune away. Frank Language was reportedly a firefighter with access to multiple phone lines that enabled him to elude the radio Whack-a-Mole that ensued when he called and said, “Fass, you’re a commie nudist.” Fass would cut him off and answer the next call, which of course was Frank Language.

Fass could be considered an influencer decades before the term came into current usage. His listeners were treated to live performances on the show from a host of unique musical artists, some of them making their broadcast debut. Fass is credited with jumpstarting the careers of David Bromberg and Jerry Jeff Walker, who performed “Mr. Bojangles” for the first time on the radio as a guest on Radio Unnameable. Other guests included Joni Mitchell, Odetta, Carly Simon, Taj Mahal, The Incredible String Band, Moondog, The Holy Modal Rounders, Tiny Tim, Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan, who took listener calls and did comedy bits with Fass.

A new comedy act known as Stiller and Meara came on before they hit the bigtime. The satirist Marshall Efron, who gained fame on WNET’s irreverent variety show The Great American Dream Machine, was a Radio Unnameable regular, as were ’60s counterculture activists such as Abbie Hoffman, Paul Krassner and Wavy Gravy, who called in from Berkeley, Calif., and declared, “You’ve got Gravy in your ear!”

Cannabis fueled much of the on-air merriment. Fass was a frequent toker when the mics were off, as were his guests. His hunger for both herbal stimulants and female companionship was legendary. A string of young female volunteers who served as his assistants became romantically involved with Fass. Some at WBAI disparaged them as the “Fass Bunnies.”

Fass had three weddings, though only two resulted in legal marriages. His first marriage ended after his wife came home and found him in bed with two women. He once referred to the sexual revolution of the 1960s by joking, “There was Viagra in the water.”

From 1977 to 1982, Fass was off the air after WBAI management removed him due to his participation in a staff takeover of the station over programming policy. At the height of its popularity, Radio Unnameable was five hours long and aired five nights a week.

Listeners who called in could be mobilized. One result was a fly-in at Kennedy Airport in 1967 where 3,000 people, many of them high on weed, showed up to greet arriving passengers. Fass and the cabal also organized a Central Park be-in and a “sweep-in” on the Lower East Side.

During a student protest at Columbia University in 1968, Fass opened up WBAI’s phone lines to campus activists who were occupying the president’s office. In 2016, the university acquired Fass’ archive, which includes 10,000 hours of Radio Unnameable air checks. Sean Quimby, then director of Columbia’s library, called the archive “historically valuable.”

The show drew aspiring radio makers to WBAI, some of whom went on to illustrious careers in broadcasting. “There was this incredible program where you could hear anything playing next to anything else,” recalled Paul Fischer. “I decided that I had to go volunteer at that place.” Fischer went on to become news director at WBAI and later went to work at CBS, writing for Dan Rather.

In addition to Fischer, Josephson and the late Steve Post are among the WBAI alumnae who credit Fass with jumpstarting their careers.

“Bob was generous to those of us on the way up,” Josephson told Current. “Without Bob Fass advancing my career, I would be a well-pensioned IBM executive, instead of a penniless radio host.”

Jan Albert, a WBAI producer who went on to become an Emmy Award–winning television producer, said on Facebook, “I can tell you that working on his show in the early 1970s was an ongoing parade of life and an up close, great history-as-it-happened lesson. Just what he taught me about music alone, I’m still enjoying almost 1/2 century later.”

In 2018, with his health failing, Fass was confined to the ground floor of his home on Staten Island, where he continued to do the show. At that point, Fass was on for just three hours one night a week. He left New York for Monroe, N.C., in 2019 and continued to do the show from his home.

Fass is survived by his wife Lynnie, nephew Sam Fass and niece Nancy Fass Rasmussen.

One of the very greatest Americans! Thank you Mr.Case and Godspeed to his beautiful family!

Bye-bye!