He drove them crazy, but reporters will miss ‘unstoppable’ NPR arts editor Tom Cole

Ben Cole

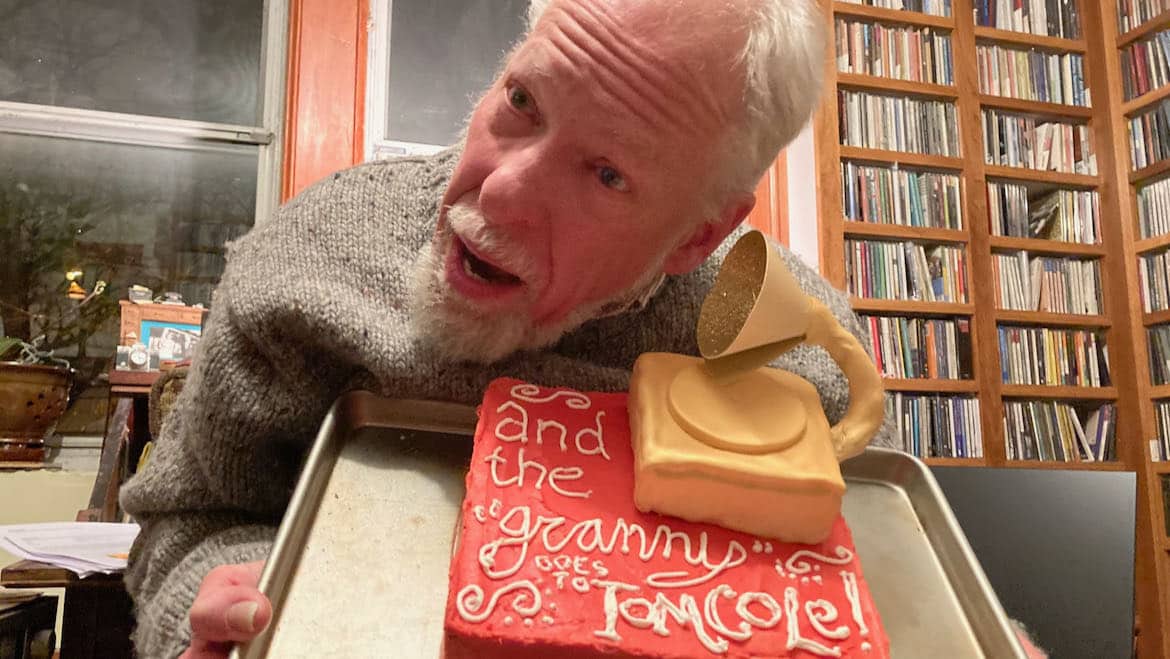

Tom Cole with a cake made by Petra Mayer, an editor for NPR Books.

Over the course of the 40 years I’ve freelanced for NPR News, I’ve worked with some great editors. But there have also been some real doozies.

An editor who came to NPR from CBS admonished me not to “bite the hand that feeds you” after I complained about her chronic failure to submit paperwork for payment. Another editor, a notorious sexual harasser now deceased, assigned a secretary to edit me.

And then there is Tom Cole, a senior editor on NPR’s Arts Desk who retired this week after 33 years at the network.

Like many of the reporters who collaborated with him over the years, I know that Cole was the best editor I have worked with my entire career. But as more than one of his colleagues noted at his farewell Zoom party Jan. 15, editing with Cole was at times the journalistic equivalent of waterboarding. Many a public radio journalist fumed while waiting for the man to call them back to resume an edit.

Cole’s legendary time-management issues were playfully lampooned by Arts Desk freelancers Jeff Lunden and Naomi Lewin in a parody of the Broadway show tune “Mame” they recorded for Cole’s Zoom farewell.

You said you’d do an edit at 10, Tom

It’s now 12:20, please tell me when, Tom

You might be calling. It would be oh so very helpful just to know

How long we will be sitting and waiting for the guy we’ve dubbed Godot

For a couple of years I vented about the Waiting for Tom Cole process in logs of our edits that I showed no one. During an edit for a story about mixtapes in January 2004, there were 23 entries in the log detailing edit appointments made, broken and rescheduled with ostensible reasons (“snow,” “death of Captain Kangaroo”).

Breaking cultural news did take its toll on Cole’s ability to work with reporters at previously arranged appointments. But why would it take nine months to finish an edit on a story with a member station reporter? That’s what happened to Anita Bugg, whose piece on the Texas singer/songwriter Vince Bell aired on Weekend Edition Saturday in January 2000. Bugg was Nashville Public Radio’s news director at the time.

Bugg is now VP for programming at the station. She had encouraged one of the station’s reporters to pitch music stories to Cole but warned her about his rep as a curmudgeon. The reporter, Jewly Hight, is one of several freelance or member station reporters who share the experience of badgering Cole for a year or longer before he accepted their first story. Finally, in 2014 Hight got a go-ahead from Cole to do a piece about elderly country balladeer Mac Wiseman. She has filed stories on Nashville’s country music scene regularly for Cole since then.

“He was someone who, if you do good thinking and have good ideas and and then bring him good writing and good tape, then you can earn his respect and trust forever after,” said Hight, who recently was hired as the editorial director of WNXP, Nashville Public Radio’s new music station.

In the six years she worked with Cole, Hight said, they laughed a lot during edits. Hight would intentionally write a descriptive phrase she knew would cross the line Cole drew between criticism and reporting, or stumble on purpose during the recording of her voice tracks and then curse, “just for his amusement, just so that he would have to cut it.”

A few of the reporters who participated in the Zoom farewell recalled being amused by the sounds Cole made during edits, including gum-chewing, eating lunch and what one reporter described as something that sounded like a cat coughing up a hairball when he expressed his displeasure. And as much as Cole fought for airtime for his reporters’ stories, he also fought with his reporters.

“Over these many years we’ve had breakups, usually initiated by me,” said Karen Michel, a veteran freelancer who worked with Cole for most of his 30 years on the Arts Desk. “I truly love the guy, no matter how crazy he makes me.”

Asked about the chronic cancellations and delays in editing, Michel replied: “The bottom line is, people would put up with that because he was a great editor.”

“A couple of times over these 30 years, I’ve left a message saying, ‘You know, I have better things to do than wait for you,’” said Howie Movshovitz, a Denver-based freelancer who has taught at the University of Colorado and been a film critic for member stations KCFR and, currently, KUNC.

“My wife once said that listening to us on the phone was like listening to an old married couple,” Movshovitz said.

But Movshovitz said the breadth and depth of Cole’s knowledge of the arts always impressed him, a sentiment shared by Michel, who said, “No editor at NPR I have worked with made sure they knew the subject as well Tom did.”

Although Cole denies that he generated more stories and got them on NPR’s daily newsmagazines than other editors at the network, former and current NPR staffers say otherwise.

“Tom champions the work of reporters with a zeal and passion that doesn’t always get the appreciation it deserves within the company,” said Laura Bertran, who served as senior editor on the Arts Desk until taking a buyout and retiring in 2012. “He’s a very strong advocate for the work of the reporters that he edits. He gets it on the air.”

Shereen Marisol Meraji, host and senior producer of NPR’s Code Switch, is one of several reporters who referred to Cole as one of their favorite editors. Recounting the time he went to bat for her during the edit of a piece about 1993, a golden year of hip-hop, Meraji told Cole’s Zoom gathering about one actuality in the story in which a rapper said, “You got to treat the rap game like the dope game. You feel me? It’s a beautiful thing. You’re claiming more fame than the dope game. You’re making more money than the dope game. And it’s more legal than the dope game.”

“I think most editors would have been like, ‘Could you choose another quote?’” Meraji told the Zoom gathering. “But Tom was, like, ‘Okay, yeah, we’re gonna go with this.’ The story got turned down by ATC, and he’s like, ‘No problem. We’ll find another show that’ll take the story.’”

He did find another show: Morning Edition.

“Tom would walk into the studio with a four-reel mix, and you knew it was probably going to be the hardest thing you did all day — or all week. But it was also going to be the best thing you did.”

Stu Rushfield, “Weekend Edition” technical director

At one point there were 112 people in the Zoom call, some as far away as Asia and the Middle East. Among the well-wishers was Bilal Qureshi, a 2007 Kroc Fellow who went on to serve as a producer and editor on All Things Considered. Qureshi now freelances for the network.

“I initially thought when I would pitch things to you and you would accept them, that it was kind of amazing that my marginal ideas could air in the mainstream,” Qureshi said from Dubai. “It’s been amazing how you’ve made so many of us feel like story ideas that we had could could actually breathe and exist in other people’s ears, and for that I’m always going to be grateful.”

Cole will be remembered for his devotion to the craft of making radio as much as his ability to shape stories editorially.

The Washington Post columnist Marc Fisher described G-Strings, Cole’s Sunday-morning music show on Pacifica outlet WPFW-FM, as “a jazz breakfast that sounds like sunrise.” And NPR senior arts critic Bob Mondello noted that when it came to mixing, “Tom could kind of make your voice float on the music in a way that had to do with the rhythms of your speech and the rhythms of the music so that it feels bigger than what you’ve written. You feel like there’s more there.”

At the Zoom farewell party, Stu Rushfield, technical director of Weekend Edition, recalled the old predigital days when radio stories were edited and mixed on reel-to-reel tape recorders.

“Tom would walk into the studio with a four-reel mix, and you knew it was probably going to be the hardest thing you did all day — or all week,” Rushfield said. “But it was also going to be the best thing you did.”

At first, Cole didn’t object to the switch to digital editing because he was allowed to work with an engineer in a studio. But when the network decided that editors would mix without an engineer at their desks, that was a problem.

“What I didn’t want to give up was going into the studio and collaborating with the engineers,” Cole said. “I’m a second set of ears for the reporters, and the engineers were a third set of ears for me and the reporters, and it was invaluable. Something has definitely been lost in that.”

NPR listeners have heard his voice in voice-overs he did for other reporters’ stories, providing translations or dramatic readings. “If we needed a voice-over, we always thought of Tom Cole, even if it was a five-year-old girl in Chile,” said Weekend Edition Saturday host Scott Simon, who joked during the Zoom party that Cole had done “several popes, a number of assassins, Hemingway, Ferlinghetti, Shirley Temple Black, Ferdinand Magellan, Ferdinand Marcos, Marco Polo and Tinkerbell.”

Cole did his own stories as well, a somewhat intimidating experience for colleagues tasked with editing the great editor. He filed features and obituaries for many musicians, especially jazz artists and guitarists — everyone from Dick Dale to Django Reinhardt.

In addition to playing a pivotal role in the broadcast of stories about artists the mainstream ignores or undervalues, perhaps Cole’s greatest achievement at NPR is shepherding two generations of newcomers to public radio journalism.

“If I had a role in getting new voices on the air, getting different voices on the air that might not have been heard, then maybe I accomplished something,” Cole told Current. “I’ll say it now that I’m not there anymore: NPR was founded to provide an alternative to mainstream media, [but] it has become more and more mainstream over the years, and I think that’s sort of drifting away from the mission.”

I’ll leave the last words to two women who are reporters on the Arts Desk. Cole’s wife, Elizabeth Blair, said: “With him going away, I worry — will other editors have the energy to fight as hard as Tom did? Tom was unstoppable.”

And when asked whether the Arts Desk will hire a replacement for Cole, Neda Ulaby, who described Tom Cole as a “powerful moral figure,” said, “How does this guy possibly get replaced? He can’t be replaced.”