American Archive collaborations expand scope, purpose of digital collection

Courtesy Hannah Hurdle

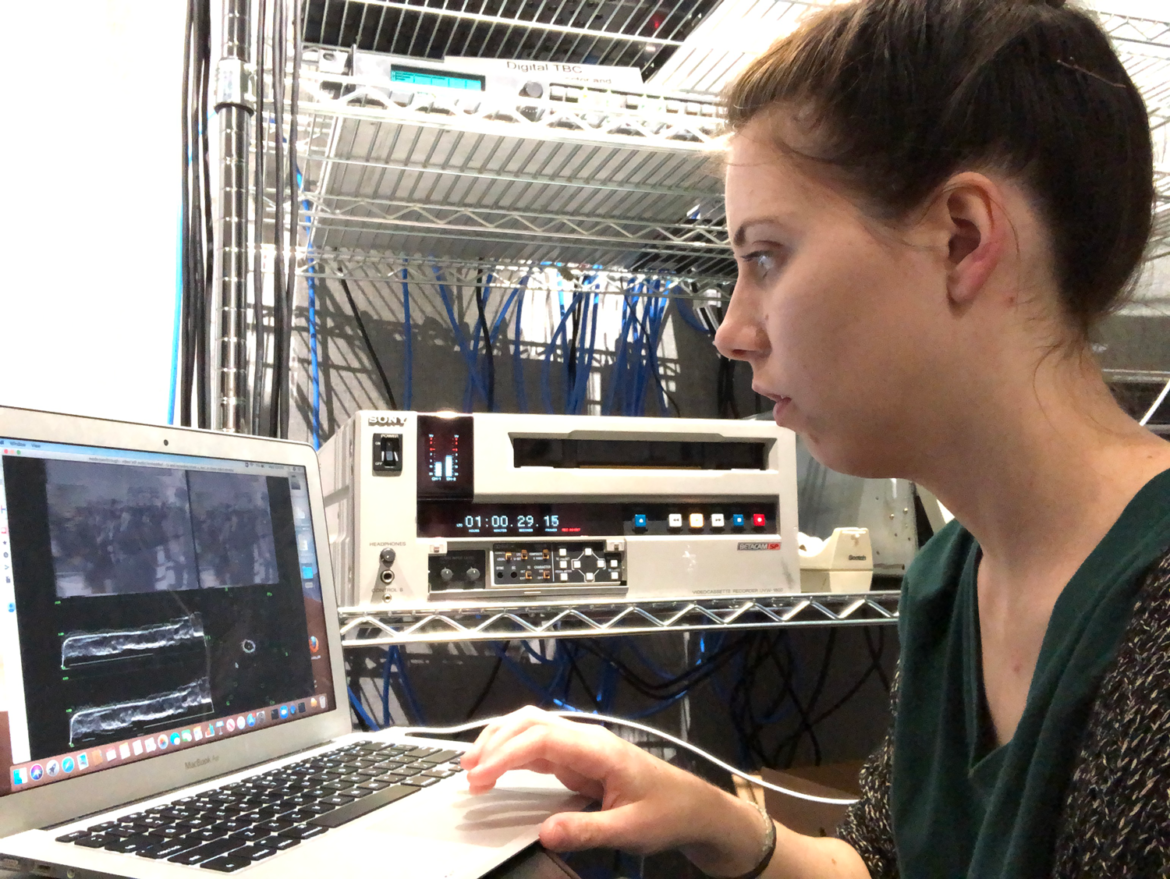

Hannah Hurdle, a fellow in the University of Alabama collaboration with AAPB, runs a capture on a Betacam SP deck at her workstation in Tuscaloosa.

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting has expanded its efforts to digitize and preserve historical public broadcasting content, building on its outreach to offer more archival support and new technology solutions.

Through direct connections with stations and minority consortia, AAPB staff have been working to identify and preserve media created by people from historically marginalized groups. This summer, a new fellowship program at the University of Alabama’s School of Library Sciences placed graduate students at three public media stations that needed assistance with preserving their archives.

AAPB is working with the Center for Asian American Media to digitize and preserve its programs, according to Casey Davis Kaufman, associate director of the WGBH media library and AAPB project manager. It has also partnered with the Latino Public Radio Consortium to raise funds supporting preservation of its archives.

Another collaboration is designed to help accelerate the preservation process across public media and make the digitized content more accessible to the public. Brandeis University’s Lab for Linguistics and Computation is working to create open-source software that can review digitized content and automatically generate metadata, including names, dates and program titles.

AAPB is a collaboration between WGBH in Boston and the Library of Congress to preserve and digitize public media’s program archives. CPB funded its launch in 2013. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation began supporting efforts to hire staff and expand outreach and preservation work in 2017. The foundation renewed its funding in September, providing a two-year grant that includes support for the technology collaboration with the Brandeis University lab.

AAPB has preserved more than 40,000 hours of programming since the collaboration began in 2012, but that content is only a “drop in the bucket” compared to the material that could be lost within the next several years, Kaufman said. Software that automatically creates and adds metadata about the programming to the archive will allow AAPB to process and upload content faster.

“Once [media] is digitized, we don’t want it to just sit there,” Kaufman said.

“It’s not a stretch to say that a huge amount of the intellectual and cultural content of the United States is in danger of falling apart in the next 10 to 15 years.”

James Elmborg, director of the Public Broadcasting Preservation Fellowships at the University of Alabama

Identifying and preserving programming that is culturally and historically significant remains a big focus for AAPB, and new partners share a sense of urgency about the work ahead.

“I know that most stations are focused on new content, but … it’s really important that we make sure their histories are adequately preserved: the communities, the stories, and the people,” Kaufman said.

“It’s not a stretch to say that a huge amount of the intellectual and cultural content of the United States is in danger of falling apart in the next 10 to 15 years,” said James Elmborg, director of the public broadcasting preservation fellowships at the University of Alabama’s School of Library and Information Studies. The program, which began in July, pairs graduate students with public media stations. This fall, fellows are preserving at-risk material of local significance at Richmond-based Virginia Public Media, the Center for Public Television and Radio at the University of Alabama, and WSRE in Pensacola, Fla.

The fellows’ primary role is as “community archivists” who allow “people to be the tellers of their own story,” said Elmborg. Their efforts include building relationships with media producers in communities that have been under-represented in media and working to preserve content overlooked by other preservation projects.

In its work with CAAM, AAPB sought to fill a gap in its collection, according to James Ott, CAAM’s director of administration and finance. Archivists reached out to CAAM after noticing the database lacked media produced by Asian Americans, he said.

CAAM and AAPB focused on preserving 60 films, produced largely by independent and local Asian American filmmakers, Ott said. The collaboration was guided by AAPB’s recognition that CAAM provided subject expertise in deciding which programs would best represent Asian American voices in the archive.

“We hope, of course, that this is only the beginning,” Ott said.

‘This isn’t … rocket science’

Kaufman provided a “very rough” estimate of the workload that AAPB is trying to manage. If one person spent 15 minutes viewing each of the 68,000 programs that were digitized in the earlier CPB-managed archives project — and never took vacation time or sick leave — it would take 32 years to add metadata to all the material that public broadcasters preserved prior to 2013.

Software that automatically creates and adds the metadata will allow AAPB to process and upload content faster. Ultimately, the metadata makes content in the database easier to search and discover.

“This is not groundbreaking, Nobel Prize–winning rocket science,” said James Pustejovsky, professor of computer science and director of the Brandeis Lab for Linguistics and Computation. Pustejovsky teaches courses in machine learning, computer science and data analysis with a focus on natural language processing. “It’s just putting things together for the community to make it accessible to people who have a right to have these kinds of tools.”

The Lab will adapt existing artificial intelligence technology and other tools that process subtitles, speech, and other data for AAPB’s database. The scope of work includes developing new tools for the archive and other public media preservation projects.

Pustejovsky’s original focus for the partnership was to develop speech-to-text software that produces complete transcriptions of archived programming.

For film and video programs, such as a news broadcast about a protest that includes video of protest signs, the tools that capture the text in such visuals are often very expensive, Pustejovsky said. The lab took on the work of creating open-source software to capture data from such images, he said.

“I’m very, very firmly committed to making this type of stuff available to people, particularly those who really are underpaid and under-resourced, providing information to their communities, libraries, and archives. … I want to help them out as much as possible,” Pustejovsky said.

An earlier version of this article reported that AAPB was actively working with LPRC on preservation of its archives, but the two organizations are collaborating on fundraising to support an archives project. In addition, Kaufman’s estimate of the 32 years it would take for an archivist to add metadata to the AAPB collection has been corrected. In the earlier version, Kaufman said the estimate applied to 100,000 items that AAPB has already digitized, but she was describing the task of adding metadata to 68,000 public broadcasting programs that were preserved prior to 2013.