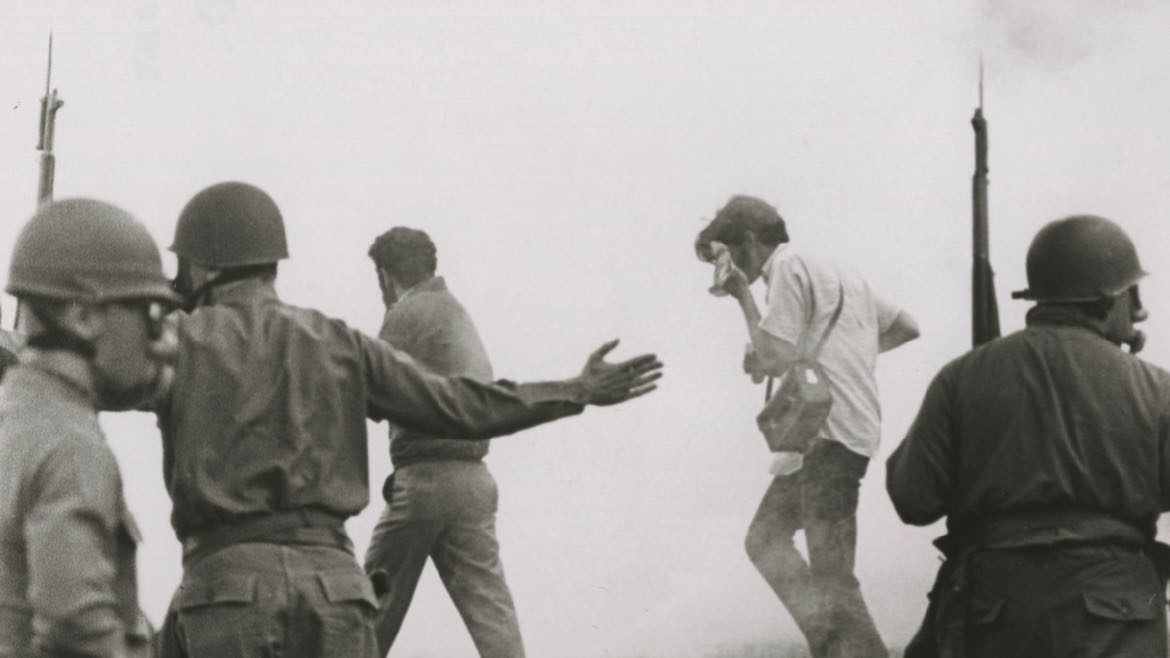

In 1970, riots and tear gas couldn’t sideline Ohio’s WOSU — but its licensee’s president did

Riots on the campus of Ohio State University in 1970 shut down the school and WOSU.

A new book by WOSU Public Media GM Tom Rieland chronicles the 100-year history of the Ohio radio and TV station. Published in April, Sparks Flew: WOSU’s Century on the Air traces the station’s growth from its roots as one of the first educational broadcasters in the country. In this excerpt, Rieland revisits how WOSU fared during a time of social tumult on the campus of Ohio State University, its licensee.

April ended at Ohio State with the sad and curious spectacle of those who claim to strive for mankind’s peace and dignity and reason, systematically beating other people on the head in the contradictory and self-defeating effort to achieve those ends.

Dick Hull, Director of WOSU Radio and Television, in an April 1970 memo to staff

March 22, 1970, marked the one-hundredth anniversary of Ohio State’s founding. The university celebrated with a number of events, including a documentary produced by the photography and cinema department that aired on WOSU. In April the Center for Tomorrow on Olentangy River Road was dedicated on the fiftieth anniversary of the first radio broadcasts at Ohio State. It would soon become the new home of WOSU radio and television.

The anniversary celebrations couldn’t mask the continuing unrest on campus. Women demanded equal rights, black students sought civil rights and representation, and student protestors demanded an end to the Vietnam War. The board of trustees and much of the university’s leadership consisted of older, white, conservative men who couldn’t understand and wouldn’t put up with student tumult. It was a tense situation, and WOSU was ideally positioned to cover its many angles.

Radio program director Tom Warnock and news director Don Davis had applied for and received the first news production grant from the recently created Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The five-year grant resulted in an incredible growth spurt for the news division, from two full-timers to some twenty full- and part-time producers and reporters. It was now the largest radio news staff of any station in Ohio and allowed WOSU to develop two daily local blocks of news, sports, and weather called News ’70 airing from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. News ’70 premiered less than a month before the biggest upheaval ever seen at Ohio State.

On April 29 a student rally attracted more than two thousand people and left the campus literally in tears. The rally was put together by the Ad Hoc Committee on Student Rights, which had presented a series of demands and called for a student strike until the administration negotiated. In the midafternoon, police and protesters clashed at Neil and 11th avenues, where students had staged a sit-in. Columbus police showed up in riot gear and began firing tear gas to disperse the crowd.

At the WOSU studios the chemical wafted through the open windows, causing coughing, sneezing, and watering eyes. Reporters scrambled across campus to gather stories for emergency radio coverage. Davis recalled that one reporter was knocked out after being hit in the head by a tear gas canister. Davis himself was overcome as he tried to cover events on the Oval, in the heart of campus. “The Columbus police shot off all their tear gas during the day and into the evening, a year’s supply in one day,” he said. The gas forced WOSU’s instructional television offices and the studio in Derby Hall to close up.

WOSU covered the riots as thoroughly as they could, but not without some consternation on the part of administrators. “I know there was a time during the riots that some said we shouldn’t be broadcasting at all,” said Davis, but Vice President John Mount told university leaders that “as long as they follow the rules and standards and good practices of journalism, I think they should broadcast.” It was a rare vote of confidence from the administration.

The confrontations between demonstrators and police continued into the night until Columbus mayor Jack Sensenbrenner declared a curfew for the campus area and the National Guard appeared on the scene. About fifty people were injured, including eighteen students, twenty-five police officers, and some nonstudents.

Historian Bill Shkurti said the riots were especially complex because they weren’t about a single issue: “Fundamentally, this was a revolt against the university. There was discontent from the students during a period when the university had to manage enormous growth. They didn’t manage the human side very well. The university worked very hard to keep the lid on in terms of student protests. The problem was, they kept the lid on through the use of force. So when the lid blew, it really blew.”

On May 4, on another campus plagued by protests that spring, National Guardsmen at Kent State fired on unarmed student protesters and bystanders. Four were killed and nine wounded. At Ohio State several thousand protesters subsequently targeted a planned Army ROTC awards ceremony. Although insults and obscenities filled the air, the protest ended peacefully. However, on May 6 President Fawcett announced the cancellation of student events due to ongoing skirmishes. He said classes should continue to meet but that the time should be used to discuss the issues dividing the campus.

That afternoon protestors gathered in front of the Administration Building. The National Guard tried to push the students back with rifles and bayonets and were met with bricks and rocks. At 5:30 Fawcett announced that on the recommendation of Governor James Rhodes, he had decided to close the university. The forty-five thousand students on the Columbus campus were told to leave by noon the next day. It was the first time Ohio State had shut down since the 1918 flu epidemic. More than eighty colleges across the country closed that day due to intensifying protests over the Vietnam War and the Kent State killings.

Despite appeals from WOSU leadership, the president ordered the radio and television stations off the air. “I thought it was a big mistake,” Davis said. “We were doing almost continuous coverage, and I thought we were among the most reliable of news sources about what was happening on campus because we were right here. The administration didn’t agree.” TV broadcast coordinator Don Brown said that the station “more than at any other time provided a valuable communications link between the administration and the university community.” Merv Durea said that Ohio State leaders feared protesters might take over the radio or television operations if they stayed on the air — although, he lightly joked, students would never have found the television station since it was so far from central campus.

On May 8 Dick Hull telegraphed the Federal Communications Commission: “This is to advise that WOSU-TV Channel 34 discontinued broadcast service in Columbus, Ohio at 5 PM EDT Thursday, May 7, 1970. This decision … was made necessary by an order from the administration of The Ohio State University to close all of The Ohio State University activities. WOSU-TV will remain off the air until further notice. We will advise of any change in our status immediately.” It was the first and only time WOSU was ordered to go off the air.

After the shutdown, Tom Warnock wrote a compelling note to the radio news staff mentioning the many student reporters who had worked long hours and braved the threats of physical violence to cover the situation. “The tone of operations was business as usual in virtually every sense despite the strong waves of tear gas through the building,” he wrote. “When news of the shut-down was followed by the directive that radio be included, staff expressed concern and disappointment. Their interest was based on a professional approach and genuine belief in the value of the service they provide.”

WOSU returned to the air on Friday, May 15. Sesame Street was broadcast at 7:30 that morning, and the radio operation started airing a mix of news and classical music. The university did not entirely reopen until the following Tuesday. WOSU quickly developed a special program, Issues and Answers, that aired simultaneously on TV and radio, presenting the many voices of the protests: students, faculty, administrators, and community members.

This essay appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, Current’s series of commentaries about the history of public media. The series is created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the RPTF, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu

On May 4th, 1970 I was an OSU student and was there when protestors demanded and were denied entry into the Army and Air Force ROTC building, This was immediately after I saw the incongruity of these same protestors using their “PEACE” signs to beat counter-protestors over the head. After being denied entrance to the building the protestors response was to destroy, as much as possible, all the cars in the adjacent staff parking lot. Those cars belonged to the enlisted members of the ROTC detachment and civilian employees of OSU. The officers cars were untouched because they were in the faculty perking lot on the other side of the building. Next to that parking lot was the flagpole with the American flag and a group of counter-protestors unwilling to let anyone desecrate it. The protestors were afraid to go on that side of the building after several peeked around the building and sized up the situation.