Threats are real, but benchmarks point to healthy public radio system

Gerwin Sturm / Flickr

What a difference a year makes.

Last year on June 16, the Wall Street Journal ran a detailed feature with this eye-catching headline: “Public Radio’s Existential Crisis.”

“Some of the biggest radio stars of a generation are exiting the scene while public radio executives attempt to stem the loss of younger listeners on traditional radio. At the same time, the business model of NPR — the institution at the center of the public radio universe — is under threat… [as] it faces rising competition from small and nimble podcasting companies…”

That story hit a nerve.

At the time, I spoke with a national group leader who told me: “Managers are scared.” They were concerned about national shows going directly to listeners, bypassing stations. They were worried about podcasts and the decline in pledges coming through seasonal drives.

None of those fears were irrational. The threats were all real — and still are.

The ‘crisis’ has passed.

If there were a 2017 counterpoint to that WSJ piece, it was a small article from Crain’s Chicago Business, reporting May 26 on a speech by WBEZ CEO Goli Sheikholeslami, who told the City Club of Chicago: “[T]he city and the country need independent reporting today more than ever. That’s particularly true given the decline of traditional news outlets and the consolidation in the industry.”

To address that need, Sheikholeslami was expanding her news staff: WBEZ would soon have 68 reporters, editors, producers and hosts, “up from 56 today.” By the end of 2020, the news production team would be 90 strong.

If those numbers hold up, I think we can say that the “existential crisis” has passed — and not just in Chicago. Renewed confidence in the future of public radio is showing up all across the country.

Instead of faltering with the retirement of long-time NPR talk show host Diane Rehm, WAMU attracted an 11.0 share in January, the month after Rehm’s midday program was replaced by 1A. With that audience, WAMU overtook WTOP-FM as the top-rated news radio station in Washington, D.C. In the same ratings period, KQED-FM was number one in San Francisco and WUNC held the top spot in Raleigh-Durham, N.C.

In a June 26 speech to the Public Radio News Directors conference, NPR News VP Mike Oreskes beamed with pride and optimism as he noted that public radio hauled in three quarters of the regional Murrow Journalism Awards presented by Radio Television Digital News Association for 2017.

And, “Our biggest reward [at NPR],” Oreskes explained, “has been the audiences flocking to us. You all know the numbers … public radio is up double digits since 2015.”

Revenue is up as well

I expect we will hear more of the same optimism, in different forms, during the Public Media Development and Marketing Conference, opening Thursday in San Francisco.

In the annual “State of Membership” session presented by Target Analysis Group, Deb Ashmore and Carol Rhine will report that over three quarters in fiscal year 2015–16, Target-enrolled stations experienced both file expansion and revenue growth.

When Jim Taszarek and his staff at Marketing Enginuity meet with their clients, they will be looking to extend a metric Jim recently shared with me: “aggregate underwriting sales growth of 5.8 percent (July 2016 through March 2017) across all our markets.”

How did the WSJ get it so wrong?

It’s worth revisiting the WSJ piece to examine how a distinguished news operation like the Journal could publish a feature that, one year later, seems so totally off the mark.

First, the WSJ analysis placed too much emphasis on personalities and individual programs. It didn’t consider the value of what business analyst Clayton Christensen calls the “job to be done.”

Christensen, the world-famous Harvard professor who helped define the cycle of digital disruption in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma, tells his clients: “What [businesses] really need to home in on is the progress that the customer is trying to make in a given circumstance, what the customer hopes to accomplish.”

Delivering on this personal service value is a key to business sustainability in the digital age.

The WSJ article correctly identified a serious challenge for public radio: the impending retirements of Diane Rehm and Garrison Keillor, and the eventual cancellation of Car Talk. Each of these rare talents created programs that helped define public radio. They may never be adequately replaced. But their programs were part of a larger package that we call “the news/talk format.”

Today WNYC calls that package “NPR News and the New York Conversation.”

This combination of journalism and conversation, supported but never defined by personalities, has been the driving force behind the continued growth and vitality of public radio in the United States for the last 20 years.

This is the platform that WBEZ, KQED, WBUR in Boston, Oregon Public Broadcasting, St. Louis Public Radio, Georgia Public Broadcasting and NPR itself are seizing with more authority, more staffing and more support than ever before.

As NPR’s Oreskes described in his PRNDI speech last month, stations are using this platform and service package to deliver “Reliable, verified facts. Civil, informed conversations. Deeper thinking and broader perspectives.”

Today’s public radio is more than “just radio.” It is more than entertainment, more than companionship — which are powerful qualities of good radio.

As the news ecosystem has changed, public radio has, increasingly, been developing the capacity to meet “an undeniable increased need for a fair, truly independent voice to deliver the facts, and that is where we [at WBEZ] come in.” This is how Goli Sheikholeslami explained the job being done by her station in Chicago.

Growth of legacy business model

The second weakness in the WSJ analysis was underestimating our collective financial strength. At least so far — an important caveat — our corner of the media world does not look like daily newspapers, the recording industry or other fields that have been devastated by digital disruption.

The total public radio station economy reached an all-time high in 2015, the last year for which I have reliable data. I think it’s safe to assume revenues continued to expand in FY16, likely reaching $1.1–1.2 billion.

Instead of contracting under digital competition, the legacy business model for public radio continues to expand.

All around the country, listeners are voting with their wallets and supporting that package of “NPR news and [our city’s] conversation” through monthly sustainer plans. These, in turn, are helping stations expand donor files and lifting average “dollars per donor” in annual giving.

Improvements in the business outlook helped propel underwriting sales in FY15 to all-time highs after a half-decade of depressed results following the 2008–09 recession. If many of the large and mid-market stations are seeing the same revenue increases that Jim Taszarek reports for Market Enginuity stations, I think it is safe to assume that underwriting gains have continued through 2016 and into 2017.

Meanwhile, the case studies we have been developing in the Futures Forum document the role that local foundations and philanthropists are playing, providing seed capital for local news beats, investigative reporting and community engagement efforts.

Most encouraging, for me, are the fundamental trends. Individual giving, underwriting and foundation support, which together provide 70 percent of total station revenue, look reasonably strong in the near term:

- The conversion of annual donors to sustainers will continue.

- Larger stations will continue to build their major donor programs, the fastest growing piece of the public radio revenue picture.

- The need to preserve local news and information services will drive philanthropic support for public service journalism.

Even more important than revenue expansion, however, is how money is being invested.

Here again, the story with the NPR station network is encouraging. Programming and production investment has grown every year for a decade among the news/talk cohort of stations and licensees that provide multiple service streams. The latter group includes WNYC, Minnesota Public Radio, Louisville Public Media and Capital Public Radio in Sacramento, Calif., each of which features a robust 24/7 news/talk component.

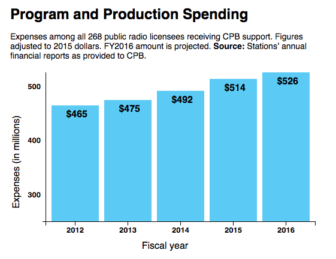

As a whole, all 268 public radio licensees that receive CPB support now spend more than half a billion dollars each year on programming, up $61 million (+13.1 percent) from FY12.

From what I can see, an increasing portion of that total appears to be devoted to local service.

From what I can see, an increasing portion of that total appears to be devoted to local service.

And the relationship between the overall health of the public radio industry and the growth of news/information services shows up in every key financial measure, except tax-based support.

For the last few years, I have been tracking the growth of the “top 125 licensees” providing news/information in public radio. This is an inexact description of this group, because it combines the financial performances of single-format, all-news stations such as KPBS in San Diego, with licensees like Louisville Public Media, whose financial reports include an all-news service and two music stations.

Their financial performance shows the dominance of this “news cohort.” In 2015, this group took in:

- 77 percent of the total station revenues;

- 77 percent of member revenues;

- 79 percent of underwriting; and

- 86 percent of major gifts.

The percentage of station-based program and production spending in this news cohort increased steadily, from 71 percent in fiscal 2008. Assuming that spending continued to expand at the average rate over the prior four years, then the percentage of program spending in the news cohort (vs. the whole 340 public radio stations) will reach 79 percent in 2016 year.

Several factors combined in a virtuous cycle to drive public radio growth — expansion of the news franchise and in the capacity of these stations to acquire resources, the willingness of listener/members to provide support and ability to secure investments from major donors and foundations. We’re now in as good as position as we could possibly expect for a period of rapidly expanding digital competition.

This story of news evolution is a major part of our “Local that Works” PMDMC session to be held Thursday. We will look at how these factors combined to create two of the nation’s leading news-focused stations, Oregon Public Broadcasting and North Country Public Radio.

Keeping pace in the era of podcasts

This brings us to the final problem with the WSJ analysis: the suggestion that podcasting would become key digital service that punctures the public radio balloon.

Podcasting continues to expand, and it may pose serious competitive challenges to public radio in the decade ahead. But for now, public radio is keeping pace.

In fact, we play an outsize — even dominant — role in this emerging platform. Our capacity to compete in podcasting rests on a combination of factors.

- Demographics — Many podcast enthusiasts are public radio listeners;

- Technology — Public radio listeners adore the Apple technology that hosted the podcast revolution; and

- Core competence in high-quality audio.

Those advantages pushed public radio companies to the top of podcast rankings at the dawn of the podcast era 10 years ago, and public radio continues to dominate the medium. Of 183 million downloads reported for Podtrac’s top-10 publishers in May 2017, 73 percent came from a “public media cohort” of networks, stations and closely aligned producers. NPR itself supplied more than a third of the total downloads.

Those advantages pushed public radio companies to the top of podcast rankings at the dawn of the podcast era 10 years ago, and public radio continues to dominate the medium. Of 183 million downloads reported for Podtrac’s top-10 publishers in May 2017, 73 percent came from a “public media cohort” of networks, stations and closely aligned producers. NPR itself supplied more than a third of the total downloads.

This is the one area of digital service where public radio can now provide solid evidence of its sustainability. Demand for podcast ad placements and high CPM pricing have made podcasts a growth area for both networks and all of the major producers, including Public Radio Exchange, WNYC Studios and This American Life. And soon, at least in some markets, podcast networks may be providing geo-targeted local spot avails, opening new opportunities for local corporate support.

Beware complacency

Now that some guarded optimism has replaced all the hand-wringing triggered by the WSJ analysis, one of the dangers facing public radio is complacency. Larger stations aren’t as vulnerable to this. They are driving system growth, and their competitive challenges and opportunities for service expansion are too powerful.

For example:

Stations know they have to “be more local.” This requires a complex, expensive reorganization of staff, acquisition of new technology and new skills and creation of new, highly valued local services — everything from local journalism to greater involvement in cultivating local music.

This is why I am partnering with Current in a search for new models of “Local that Works.” You can submit your ideas and projects to our search and potentially secure a $5,000 prize for the best example, which will be featured in a general session at Super Regional meeting in September.

Our editorial network needs to be redesigned. This was the main point of Oreskes’ speech at PRNDI. He wants to create regional and state hubs capable of producing high-quality journalism, staffed by on-the-ground journalists who collectively form an integrated local/national news service that competitors simply cannot match.

Our digital services are not working very well. Apart from podcasting and streaming, digital news delivery is sub-par. Indeed, last fall NPR Digital reported that visits to station sites are now falling behind the general growth rate of online news properties. Far too many stations are spending a lot of money and staff time posting content that gets meager attention and earns little or no compensating revenue.

This underperformance in digital service is also showing up in fundraising, as my colleague Dick McPherson points out in a companion analysis he prepared for PMDMC attendees.

We have to narrow the “capacity gap” within our system. This is an issue I identified and reported on in Futures Forums presented at Public Radio Super Regional Conferences in 2012 and 2013.

What is the capacity gap? In terms of key performance measures, our largest 30 to 40 licensees are pulling further away from the rest of the pack, largely because smaller stations simply do not have and will never have the resources they need to compete. Hosting that “NPR news and [our city’s] conversation” is expensive. Expanding and servicing sustainers is complicated. Cultivating major giving requires more staffing. Developing digital service requires technology and skills that often beyond the financial capacity of a small station.

Over the last five years, nothing has changed for the better. Smaller, stand-alone NPR affiliates in rural areas and small cities are not growing. Even the best, like North Country Public Radio, are growing too slowly to sustain their transition to “be more local” without some fundamental reorganization, shifting costs and capacity sharing. This opens new opportunities for shared revenue growth.

This issue needs an influential champion, respected throughout the system, who can develop some options and get this discussion started.

To remain a true national service, we need some kind of Marshall Plan for our jazz stations, our small and mid-sized mixed format stations, and some struggling state networks. If we want to face the future with the rising confidence that is spreading among our leading and larger stations, it’s an issue we need to resolve.

Mark Fuerst is director of the Public Media Futures Forums, created by the Wyncote Foundation to support the analysis of issues that will shape the next decade of public media service. Before developing the Forums, he was co-founder and director of the Integrated Media Association, where he managed national new media conferences and research projects in online fundraising, email/e-communication and audio streaming. Current is funded in part by the Wyncote Foundation.