Needed: courage to shape digital video future

‘Invent it.” Those are powerful words, inspirational words. Who among us hasn’t sometimes dreamed of being an inventor? They’re also scary words. “Invent it.” It’s easy to say, harder to do. Because “invent it,” by definition, means change.

Most of us want to invent, yet most of us fear change. At large organizations, the usual approach to dealing with this contradiction is that the rallying cry “Invent!” gets watered down to “innovate,” which turns into “incrementally improve.” Or “innovate safely.” Which becomes, well, Kodak.

Kodak invented the digital camera — literally. They still hold the patent. The first digital camera, invented in a lab in Rochester in 1975, weighed 9 pounds and offered the promise of a whole new world of photography. Yet instead of viewing this revolutionary technology as an opportunity to invent the future, Kodak sat on its hands, worried that the digital camera would cannibalize its high-margin film business. Rather than invent the Kodak of tomorrow, the company chose to protect what worked today. While Kodak headquarters sang “Mama, don’t take my Kodachrome away,” the world moved on.

“Invent it” is not such a hard motto to live by when you’re young. Forty years ago, an unruly adolescent called public television invented its own future — and what a future it was. Public television thrived in an era of scarcity. Three channels and nothing on became four channels and, finally, something on that was worth watching. Forty years ago our predecessors invented the future.

Today, the media world has flipped from scarcity to abundance — where iPhones shoot HD feature films, where cable turns those four channels into 400, and then web, mobile and other platforms rocket the number to 4 million channels. And that’s what keeps all of us up at night, isn’t it? Our challenge, our dilemma, our doubt is this: In an era of abundance, can public television do it again?

“The TV set isn’t just for TV anymore,” Seiken says. He challenges pubTV stations to compete to become major sources of online video to home TV receivers.

Today I want to lay out a vision for how we can invent our future, a future where public television is serving millions more people with billions more videos. A future where each PBS station is the YouTube of its local community — the dominant video brand every person in town wants to watch, every producer in town wants to shoot for and every business in town wants to support. A future where the technology revolution that’s so disorienting and unsettling actually enables us to invent a golden age — a golden age of mission and a golden age of sustainability.

For the next few minutes I’m going to walk you through how, together, we can take the first steps toward creating this golden age, and what it might look like when we get there. And why this magical opportunity will slip through our fingers if we don’t have the courage to change.

The fight to control the eyeballs

Let’s start here: Why would I dare stand here and declare — in the face of so much evidence to the contrary — that we can create a new age of prosperity? One reason: video.

We are in the early stages of a two- to five-year land grab that will reshape the video industry in a way not seen since Hollywood in the early 20th century. For media organizations, this video revolution will determine who wins, who merely survives and who perishes.

Skeptical? Here’s the evidence. Americans are watching more video than ever. While television viewing remains steady, more than 100 million Americans now watch online video daily. Last year, visitors to YouTube viewed 1 trillion videos — 1 trillion, with a “T.” And that number is doubling every two years.

We’re not talking a vast YouTube wasteland of skateboarding gerbils. YouTube’s ambition is to be nothing less than the biggest multiple system operator, or MSO, on the planet — with an almost infinite number of professionally produced video channels. This year alone, YouTube will invest $200 million in professional productions. Millions more are pouring into startup production studios from venture capital firms. Discovery just paid $30 million for a company that’s essentially a YouTube production house.

Why is the smart money flowing to YouTube? Not because it expects a massive windfall from people watching video on their computer monitors. This land grab is all about who will control the eyeballs watching television sets. Because while the television will remain the epicenter of home entertainment, the TV set isn’t just for TV anymore.

These days, millions of people are watching YouTube on their televisions connected to Xbox, Blu-ray, Apple TV and dozens of other devices. By next year, more than half of all American television sets will be connected to the Internet. Already hundreds of independent YouTube producers are earning more than $100,000 a year. In less than two years, a startup called Maker has grown to half a billion videos viewed per month and 70 million subscribers.

One trillion views, 70 million subscribers — all going to companies that didn’t exist a few years ago. How is this happening?

Barriers to entry around video are collapsing. Lower production and distribution costs — combined with free Facebook marketing — are making the economics of the video business attractive even for programs aimed at niche audiences. As barriers come down, new entrants are jumping in. During the next few years, we will see massive growth in the number of new producers creating programs for the Web. Then, at some point, the industry will coalesce around a smaller number of leaders. These will be the winners. We must be one of them.

Emerging from the video upheaval

On the Web, that pattern repeats itself time after time. It happened with search. Do you remember these companies? AltaVista, Excite, InfoSeek, Magellan, OpenText, Snap, Lycos, WebCrawler, HotBot, Ask Jeeves.

They and a half-dozen more gave way to one winner, Google, and two survivors, Yahoo! and Bing. The history of the Web shows that in any sector, the winners will be few, and the game will be more or less over within a few years. As the video land-grab unfolds, we need to ensure that public television stations are among the big winners.

How? By turning the new realities of production, distribution and marketing to our advantage, paving the way for stations to become the dominant local video brands in their communities.

My vision of the future is a world where each station is the YouTube of its local community — the go-to place for video about that community. Stations, with their beloved brands, community connections, knowledge of local markets and relationships with local institutions, have a head start. But the window is short.

That’s the 40,000-foot view of the new media landscape. Video is being revolutionized, potentially in our favor. So what is PBS Interactive doing to help seize the opportunity? And what does it mean for your station?

To advance, resist the status quo

PBS Interactive’s goal is to position stations to emerge from the video upheaval not just as survivors but as winners. This will not be easy and there are no guarantees.

To make this a reality, we must clear three large hurdles:

![]() We must reinvent public television’s approach to new media technology. Today, public television does new media technology all wrong. We expect each station to develop its own independent solution — building, hosting, streaming, quality assurance and all the rest — for each platform: Web, iPhone, iPad, Android and whatever comes next. This is wrong. It’s wasteful. And it’s holding stations back.

We must reinvent public television’s approach to new media technology. Today, public television does new media technology all wrong. We expect each station to develop its own independent solution — building, hosting, streaming, quality assurance and all the rest — for each platform: Web, iPhone, iPad, Android and whatever comes next. This is wrong. It’s wasteful. And it’s holding stations back.

That’s why we’re developing the Bento project, with funding from CPB. Bento essentially is a turnkey solution for websites. Bento already has saved the PBS National Program Service more than $1 million by moving some national producers out of the web technology business. Now we are opening up Bento to stations, and we already have 41 on the waiting list. When Bento rolls out this fall, you no longer will need to build, host, design and redesign a website. You are freed up to focus on your brand, your content and your customers.

![]() We must change how we use the PBS national platforms to benefit stations. These platforms are huge. In the past three years on PBS.org and our mobile apps, videos viewed rose from 2 million a month to 140 million a month; the number of people using PBS.org and PBSKids.org doubled, reaching nearly 30 million visitors in March; and PBSKids.org has come from nowhere to become the dominant kids’ video site on the Web.

We must change how we use the PBS national platforms to benefit stations. These platforms are huge. In the past three years on PBS.org and our mobile apps, videos viewed rose from 2 million a month to 140 million a month; the number of people using PBS.org and PBSKids.org doubled, reaching nearly 30 million visitors in March; and PBSKids.org has come from nowhere to become the dominant kids’ video site on the Web.

But to what end? How does this help stations?

My vision for the PBS national platforms is that they serve as a distribution vehicle for national and local content — exposing station content to entirely new audiences. When a visitor to PBS.org clicks on the local station content, they are taken to the station site. The idea is to create a frictionless flow of audience from national to local.

This transformation is already under way.

We’ve put station branding front and center on our national platforms, including the redesigned header for PBS.org. By the end of next month, thousands of people will be watching local video from 60 stations in the PBS iPad and iPhone apps. Later this year, the video portal on PBS.org will include local video side-by-side with the primetime favorites.

Regardless of platform — be it Web, iPhone, Android, a Samsung smart TV or Apple’s upcoming iCerebellum brain implant — on any platform in any galaxy the formula remains the same: National builds it at scale, local populates it with content and the audience sees content from both national and local.

We are halfway over each of these first two hurdles — but it’s not enough. There’s a third hurdle we need to clear for public television stations to win big in the new era of video — and this hurdle is much, much more difficult. It’s not something PBS Interactive can do on its own, and it’s not something stations can do alone, either.

![]() We must work together to crack the code on exploiting the new tools of web video production, distribution and marketing, and massively expand the video footprint of stations in local communities.

We must work together to crack the code on exploiting the new tools of web video production, distribution and marketing, and massively expand the video footprint of stations in local communities.

PBS Interactive is in the early stages of working with stations and YouTube to explore tools and techniques for creating, distributing and marketing low-cost, high-quality Web productions. One example is “OffBook,” a grant-funded Web-original production for PBSArts.org that explores nontraditional art forms. It’s averaging 70,000 video views per episode, which is more than most primetime episodes. And “OffBook” costs just $600 a minute to produce.

Working collaboratively, we aim to create a playbook for how PBS member stations can dominate their local video space. This is public television stations’ birthright. This is what we were created to do but never had the resources to accomplish. Now the world has changed, and production costs are plummeting. We have the brands. We have the video pedigree. This is our moment.

What exactly does this brave new world look like?

Imagine a 20-something from Schenectady, N.Y., as she fires up her Xbox to stream Downton Abbey. Instead of seeing an isolated program, she’s captivated by an immersive public television experience, with Downton Abbey surrounded by other national and local content. After finishing Downton, she spends the rest of the evening watching dozens of WMHT programs about the Capital Region. Some are produced by WMHT, others by independent producers happy to come under the umbrella of the WMHT brand. This is the future we need to invent.

What could possibly go wrong?

Well, frankly, another possible future is the more likely one because it’s the easier future to create. All we need to do is to embrace what we humans love best — the status quo.

In his classic book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen studied high-powered companies that dwindled to irrelevance and others that reinvented themselves. What he found is this: Incumbent companies tend to work on perfecting their existing products. And while the big brands focus on perfection, they leave startups the room to disrupt them with new products.

In half the time it took public television to debate about the Prosper, the online national fundraising initiative, a startup company called Burbn was conceived, built, launched, failed, pivoted to an entirely different name and product, built the product, launched the product — called Instagram — grew to 30 million users and was sold for $1 billion. And in half the time it took for Instagram to do that, Pinterest was conceived, built, launched and has grown so large it now has six times the audience of PBS.org and PBSKids.org combined.

Instagram and Pinterest didn’t have more money or better brands than public television. Their one advantage is culture. They’re entrepreneurs. They move quickly. They favor action over discussion. They fail fast, pivot fast and try again until they get it right.

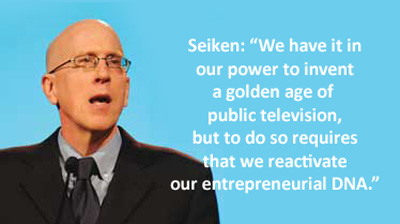

Forty years ago, our predecessors sat in rooms like this and invented the future — because they acted as entrepreneurs. We have it in our power to invent a new golden age of public television, but to do so requires that we reactivate our entrepreneurial DNA.

Fortunately, there’s an app for that. Well, not really an app, but the next best thing: a formula.

The folks at Babson College, which is the top-ranked business school for entrepreneurship, have developed a four-step formula for becoming entrepreneurial in your life or your business. Their premise is that these days every person and company needs to become entrepreneurial because “The way we were taught to think and act works well in a world where the future is mostly predictable, but not so much in the world as it is now.”

Their four-step approach to being entrepreneurial, which I’m lifting from the Harvard Business Review, is simple:

Step 1: Identify something you want.

Step 2: Take a smart step as quickly as you can toward your goal.

Step 3: Reflect and build on what you have learned from taking that step.

Step 4: Repeat.

Act, learn, build, repeat. As they say in their book, “This is how successful serial entrepreneurs conquer uncertainty. What works for them will work for all of us.”

Forty years ago, our predecessors invented the future. Were public television executives braver back then? Smarter? More entrepreneurial?

Let’s follow in their footsteps. The stars are in alignment, just as they were in the 1970s. The smart money in the digital world is convinced that we’re seeing a once-in-a-lifetime realignment of the video industry. I’m convinced that we can be among the big winners — but only if we first rediscover our entrepreneurial roots.

The power is in our hands. Will we get in the game, or just talk a good game? Let’s move fast, make mistakes, adjust and move again — all with the goal of making public television a winner in the video land grab.

The future is here. Let’s go invent it.

Jason Seiken, senior v.p., PBS Interactive, oversees the network’s new-media services, including websites and mobile products.