The accent of your musical taste

SPONSORED

By Dr. Nolan Gasser, Host of PBS’ Why You Like It: Decoding Musical Taste

Music is often referred to as a “universal language” — one that transcends the difference of spoken language and unites us in our shared humanity. This universality extends beyond our common love of music across cultures to the actual nuts of bolts of musical practice. While musical styles from different parts of the world certainly sound different from one another, there are in fact a number of “universals” that unite them all — including the prevalence of octaves and fifths, the common use of a steady beat, the use of a drone (a sustained pitch above or below a moving melody), and the common use of repetition and variation of melodic phrases, among many other things. As the famed musicologist Bruno Nettl put it, “Musics are not as mutually unintelligible as languages.” And yet, as I share in my forthcoming PBS show, Why You Like It, our individual cultures play a big role in defining our individual musical taste.

While there are indeed clear similarities or universals among the musical styles of disparate cultures, there are, of course, also clear differences — above and beyond differences in sung languages. Obvious differences include distinct types of instruments commonly used in a culture (e.g., the sitar in India, the accordion in Italy), but there are also more structural or technical distinctions that can be difficult to discern or articulate without proper training. For example, different cultures utilize different types of scales, melodies, rhythms, rhythmic meters (the way beats are organized), and performance techniques. This makes perfect sense, of course, since music — like language, dance, attire, and food — are always reflections of the people and cultures from which they stem. It is not for nothing, that is, that the music of France, Hungary, India, or Egypt “sounds” like those countries, just as their food “tastes” like them too, — so to speak.

However, unless you are raised in that particular culture, you will only obtain a partial and incomplete understanding of how the music is “supposed” to sound and proceed. The process whereby we gain this understanding is called enculturation. What is key in understanding the process of enculturation is that it does not come by virtue of explicit or formal education, although that doesn’t hurt. Instead, it is gained implicitly by informal, everyday listening—in our homes, on the radio, at the supermarket, etc. If we hear music with any regularity at all during our developing years, we automatically become encultured to it. Implied in the process, to be sure, are those universal musical elements I’ve noted above, and especially the computerlike “statistical learning” that our developing brains perform in our earliest years, from which we form “rules” governing musical practice. To complete the process, however, “culture-specific” learning is needed. This, again, arrives implicitly, merely by listening to the music of our native culture — tracking the cues that will come to concretely define those “rules.”

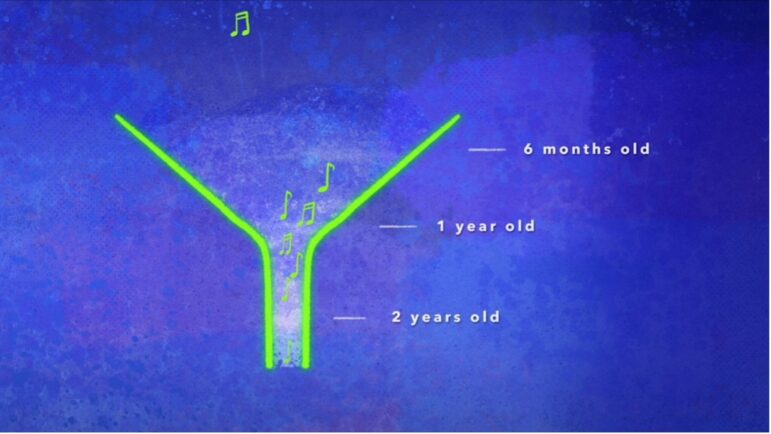

Numerous studies on infants have shown that prior to six months or so, we have virtually no cultural boundaries in our music listening — unable, for example, to recognize violations in any culture-specific manifestation of pitch or rhythm. Such “boundary-less” hearing continues even through 10 months, although the implicit learning of our native music has by then already forged some brain-based statistical learning. A watershed moment seems to be at around 12 months. By this time, infants demonstrate considerable sensitivity to musical tendencies of their own native music, yet far less sensitivity to those of a foreign culture. From the age of one, and especially age two, we start to hear music outside of our own culture “with an accent.”

The enculturation process, to be sure, continues to develop and become more complex and sophisticated throughout childhood, but even before most of us can walk, we already can recognize what makes our native music tick.

Happily, this doesn’t mean that we can’t enjoy, even love, music from another culture — even if we do hear it “with an accent.” Indeed, among the richest gifts we can give ourselves is to explore the music from other cultures — where that listening “accent” will fade more and more with every listen. So next time you go to an Indian or Mexican or Chinese restaurant, come home and check out the music from those cultures — you just might discover a new musical friend!

Dr. Nolan Gasser is a composer, pianist, author, and musicologist, best known as the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He is the author of the best-selling book Why You Like It: The Science & Culture of Musical Taste, which explores the psychology and sociology of musical preference. His forthcoming PBS special, Why You Like It: Decoding Musical Taste, airing in March 2025, brings these insights to life through live performances, animations, and an interactive app. Gasser’s original compositions include Secret Garden (SF Opera) and Cosmic Reflection (Baltimore Symphony), and his world-fusion band, The Mighty Mighty, will release their debut album alongside the PBS special. Beyond music, he co-founded Katch Data, a leading “genomic” data company working with major media players like Meta and Paramount to predict consumer taste. He also consults on music AI projects, including with Google DeepMind.

For further information please contact Deborah Radel at DRPR, deborah@drpr.us