Tag: Congress

Senate passes bill reauthorizing Ready To Learn

The requested $25.7 million in funding for RTL remains unresolved and will be taken up in separate legislation.House approves education bill that would reauthorize Ready To Learn

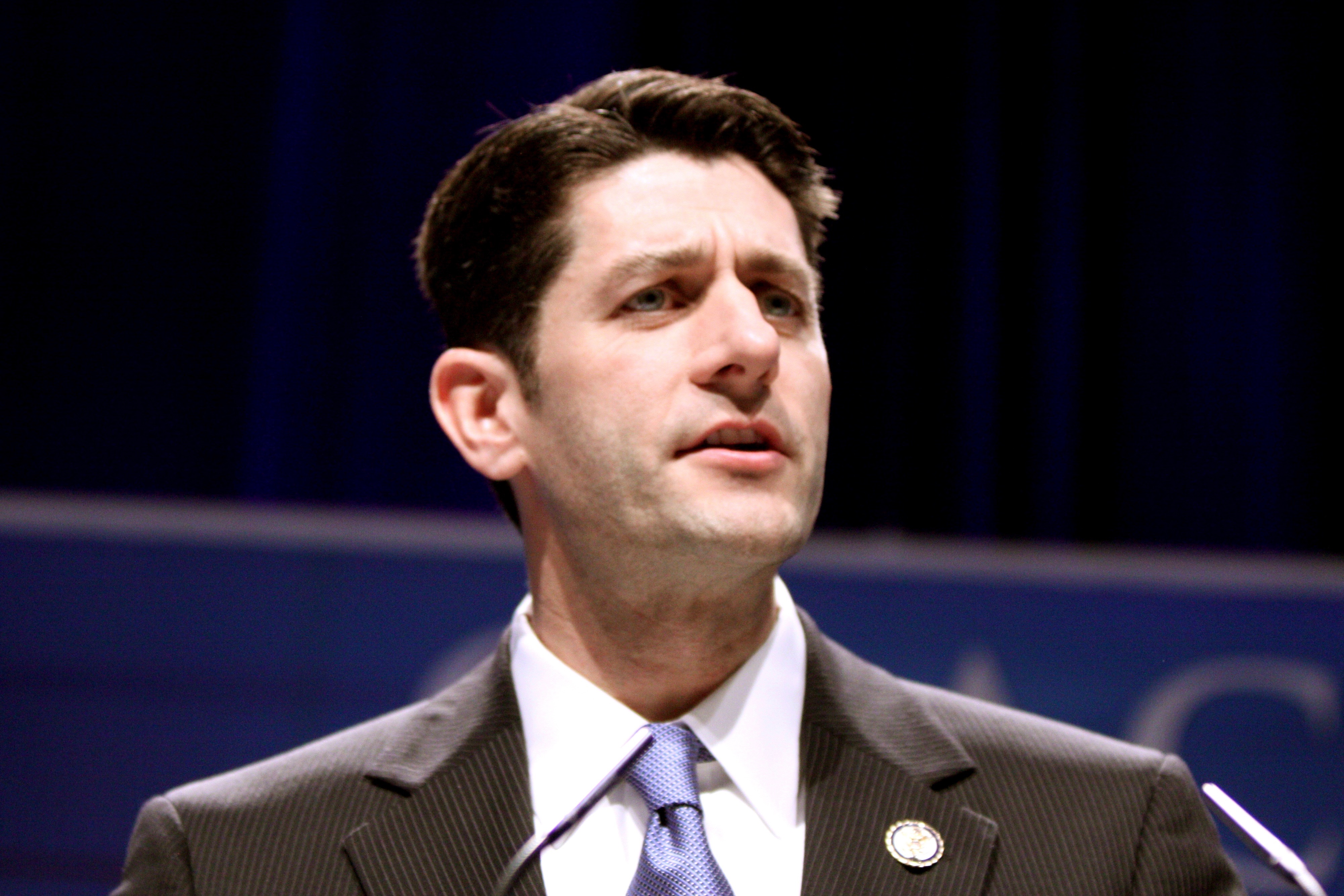

The Senate is expected to vote on the legislation Monday.New House Speaker Ryan has track record of opposing funds for public broadcasting

Public broadcasters say Ryan has always been willing to hear from them despite his feelings about federal funding of the system.Senate resolution upholds forward funding for CPB

The joint resolution approves the blueprint for the $3.8 trillion 2016 federal budget.Republicans’ proposed budget would zero out CPB funding

Though its chances of advancing in Congress are considered slim, the proposed budget put forth this week by House Budget Committee chairman ...Congress passes omnibus spending bill, secures $445M for CPB

A government-wide spending bill containing more than $1 trillion in appropriations, including $445 million for CPB through fiscal year 2016, passed the ...House Appropriations subcommittee reportedly will propose eliminating CPB

The House Appropriations subcommittee with jurisdiction over CPB is pushing once more for eliminating government funding to public broadcasting in its fiscal ...House Appropriations proposes cutting NEA, NEH funding in half

The House Appropriations Committee has proposed cutting funding to the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities by ...Ready to Compete Act introduced in House to reauthorize Ready to Learn

Rep. John Yarmuth, D-Ky., today introduced his Ready to Compete Act to the U.S. House of Representatives.Nine GOP House members express support for federal aid to CPB, PTFP

In the past week, members of Congress have sent two bipartisan letters in support of public broadcasting initiatives to subcommittee chairs in ...CPB appropriations by year

This is CPB’s account of its history of annual appropriations since its founding in more than 40 years ago. Figures shown represent ...APTS congressional champion delivers ‘tough love’ to pubTV leaders

A radio broadcaster-turned lawmaker who chairs a key House subcommittee with oversight of CPB delivered a pointed critique to public TV station ...CPB report to Capitol Hill countering “continued and pervasive” opposition to federal funding

CPB’s financial analysis on alternative funding sources for public broadcasting, prepared by consultants at Booz & Co. and delivered to Congress in ...Thicket of uncertainty for federal aid

Public broadcasters face multiple and serious uncertainties on Capitol Hill over the next few months. A spending bill approved by the House subcommittee ...APTS combats latest bids to defund CPB

Two of pubcasting’s chief critics on Capitol Hill have revived their bids to end CPB funding. Republican lawmakers Rep. Doug Lamborn (Colo.) ...