Funders of multicultural films scale back after CPB rescission

“Neptune Frost,” an Afrofuturist sci-fi musical about a hacker collective, premiered in June on “AfroPop: The Ultimate Cultural Exchange.” Black Public Media and World suspended production of the series as they seek a new sponsor.

Sandie Viquez Pedlow of Latino Public Broadcasting has been working all year to bring new documentaries from director Hugo Perez to public television.

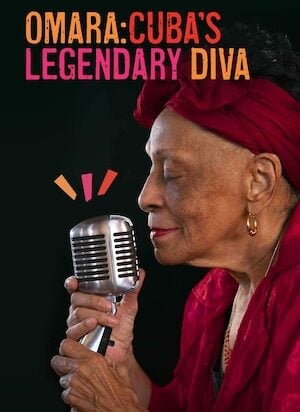

The filmmaker, who specializes in work about Latin culture, has “an incredible cinematic eye,” Pedlow said. When his latest documentary, Omara: Cuba’s Legendary Diva, debuted on PBS in September, it was presented by Voces, LPB’s documentary showcase for arts and culture documentaries.

The film is a portrait of Omara Portuondo, a vocalist for the Grammy award–winning music ensemble Buena Vista Social Club. PBS aired it last month to a favorable review in The Wall Street Journal. A feature in the Los Angeles Times noted that the documentary reveals “new depths of the singer’s soulfulness and power.”

Perez is looking for production funding for a documentary feature about another Latin American artist, and Pedlow is convinced the film will resonate with viewers around the country. But with the loss of $1.8 million in annual CPB funding, her options for supporting the documentary with LPB funding are limited.

Pedlow, who has shepherded countless films through public TV development and production for LPB and CPB, is not giving up.

LPB is one of five organizations in the National Multicultural Alliance that assist independent filmmakers with public media productions that reflect the diversity of American life and culture. Each of the independent nonprofits in the alliance — which includes Black Public Media, the Center for Asian American Media, Pacific Islanders in Communications and Vision Maker Media — function as talent incubators, grantmakers and guides for media makers in presenting their work on public media.

When the first NMCA organizations were established in the late 1970s as “minority consortia,” the goal was to open new paths for independent filmmakers of color to develop and produce programs for public television. The scope of their support has broadened to include filmmaker fellowships, digital media projects, special events and technology projects.

CPB’s annual financial support — a total of $9 million divided equally among alliance members since 2021 — was a pillar of their operating budgets. The rescission that wiped out CPB’s congressional appropriations for fiscal years 2026 and 2027 created revenue shortfalls for all of them.

CPB funding provided close to 69% of LPB’s funding in FY25, said Pedlow, LPB executive director since 2011. Now the organization is in jeopardy, she said.

At Honolulu-based Pacific Islanders in Communications, the $1.8 million from CPB provided 75% of its annual revenue, said Cheryl Hirasa, executive director.

“A lot of the news and coverage of the rescission of public media funds has been focused on stations,” Hirasa said. Stations are very important to the fabric of the country, she said, but it’s been challenging for NMCA leaders to educate the public about their organizations’ roles. Members of the alliance “are just as important because they support the independent filmmakers that provide the content that these stations distribute to their communities.”

Downsizing and difficult decisions

Since the rescission, three NMCA organizations have cut staff; all have paused grantmaking for new projects or suspended some activities while they work to secure new funding.

Vision Maker Media, based in Lincoln, Neb., is continuing its training programs for youth and emerging filmmakers but had to let go of two employees, said CEO Francene Blythe-Lewis. LPB is giving up its office space in Los Angeles and transitioning to a virtual workplace, according to Pedlow. Black Public Media, based in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood, suspended production of its series AfroPoP: The Ultimate Cultural Exchange, which was co-produced by the multicast channel World, during a search for an underwriter. The series delivered its 17th season in June.

“We are going to focus on the projects that are in … our current pipeline,” said BPM Executive Director Leslie Fields-Cruz. “We canceled our open call for this year.” PitchBLACK Forum, BPM’s annual event that draws film distributors and industry leaders for presentations of film and technology projects developed by Black creators, will continue. Its fall showcases for producers and technologists who use emerging tech as their mediums were canceled.

BPM eliminated the jobs of three employees, including its program coordinator, talent development and engagement manager and grants and development manager, in September. With permission from the affected staffers, BPM announced the layoffs in a website post that celebrated their contributions.

Fields-Cruz estimated that CPB’s annual grant represented about half of BPM’s budget. Support from the MacArthur Foundation, the Jerome Foundation and Acton Family Giving has been indispensable to BPM’s growth and sustainability, she said. “If this had happened 10 years ago, we would’ve been in much worse shape because our budget at the time was almost 99% reliant on CPB.”

Fundraising for the future

To stabilize its finances, BPM recently launched a two-year campaign to expand its donor base and raise $9 million. The idea behind the campaign, called 1.8M Donors, is to cultivate gifts from 1.8 million individual contributors or organizations. If that many donors contribute just $5 each, BPM will reach its campaign goal. Campaign proceeds will “help stabilize the organization while we continue to explore earned income revenue streams,” Fields-Cruz said. “We’re looking at building a much larger production fund that might turn into an endowment.”

Before the CPB rescission threat emerged, the Center for Asian American Media was privately fundraising. Its $15 million capital campaign, “The Future of Storytelling,” had raised $8 million during its quiet phase. Donald Young, executive director since May, said CAAM is incorporating the rescission into its campaign messaging and priorities.

“Of all the NMCA, we’re probably in a reasonable financial position,” he said.

The campaign calls for “forward-facing” grantmaking programs and engagement work, support for a new generation of filmmakers and capacity-building for CAAM itself, which is based in San Francisco. Plans included creation of at least four new jobs, but Young has applied the funds to retaining staff. His previous job as director of programs remains vacant.

CAAM’s current slate of about 35 film projects won’t be affected, Young said, but its documentary fund must be replenished before CAAM can invest in new projects. CAAM’s fellowship program, which provides career- and project-development mentorship for documentary film directors with works in progress, will recruit a new class in 2026.

Filmmaker funding in jeopardy

In a recent episode of the public media podcast Viewers Like Us, Young and Fields-Cruz said CPB had warned NMCA leaders last December to prepare “worst-case scenarios” for defunding.

Young elaborated that he had taken an earlier warning from the Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling that ended affirmative action in university admissions programs. When the decision came down, Young said he recognized that public media could soon face an “existential threat” due to political and cultural backlash against diversity, equity and inclusion.

“I think we’re seeing it play out in a very strategic, ambitious, nefarious manner. In many ways it was much more about suppressing voices,” he said on the podcast, which was hosted by independent filmmaker Grace Lee.

One of the biggest worries for NMCA leaders — and the filmmaking communities that they support — is the decimation of federal grant programs that have invested in their work and career development. That includes media programs at the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Science Foundation.

The Independent Television Service, the talent incubator and grantmaker that produces PBS’ Independent Lens, received about $19.7 million of its revenue from CPB in FY24, according to CPB data. Out of the $22.6 million in total revenues reported in ITVS’ 2024 tax filings, CPB’s support would have provided about 87% of its funding. In an Oct. 9 summary of the impact on the federal rescission on public media, CPB reported that ITVS is experiencing “a program pipeline disruption” and has laid off 13 employees.

LPB, which has a much smaller staff and production portfolio, does not have the funding to renew its Latino Emerging Filmmakers Fellowship, a two-year program that launched in 2022 with support from the MacArthur Foundation, Pedlow said. The first cohort of seven filmmakers received production funding and mentoring and other support for their projects.

Pedlow was discussing plans for a second cohort of fellows with MacArthur but put those talks on hold to focus on LPB’s fiscal stability. Budget cuts affected the jobs of two LPB staffers: one position was converted to part-time, and another staff member was let go. “I have funds to keep us going for another two-and-a-half to three years,” she said.

‘I’m trying to keep our family together’

Pedlow still holds out hope that Hugo Perez’s next documentary feature can secure funding and a home with PBS. The film is a biography of Mexican actor Ricardo Montalbán, who co-starred in Fantasy Island and portrayed Khan in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

Pedlow approached American Masters, produced by WNET in New York City, about the new project. LPB has a pipeline of documentaries with American Masters, including a documentary about playwright Luis Valdez, but there’s no commitment yet to the Montalbán film, she said. “This is all unraveling right now,” she told Current in September. “I know that they are cutting back as well.”

“I think this is a really important documentary and I’ve been talking it up,” she said. “I have to help these filmmakers bring this story to public media.”

PIC will continue its Leanne K. Ferrer Fellowship, a six-month filmmaker development program that provides funding and mentorship. The program, which is separate from the American Public Television content fellowship that also honors Ferrer, was established in memory of its executive director, who died in 2021.

Grantmaking is on hold for PIC programs that support production of full-length programs and shorts on the indigenous Pacific Islander experience.

Hirasa is balancing the needs of PIC’s stakeholders and staff as she makes decisions. “I’m trying to … keep our family together,” she said. “I really want cutting staff or hours to be the last resort.” She estimates PIC has about 18 months before layoffs will be necessary. She looks to bring in new funding by expanding philanthropic support.

In June, PIC announced a new partnership with the state government to manage grantmaking for the Hawaii Film and Creative Content Development Fund. The Hawai‘i State Legislature established the fund this year to support original works by local filmmakers and content creators, according to a news release. In its role as a facilitator, PIC leads selection of small, mid-sized and microbudget projects for seed funding. The goal is to support media projects that showcase Hawaii and distribute the work internationally. PIC will relaunch the project next year, Hirasa said.

‘Our own way of telling the story’

At Vision Maker Media, the oldest of all the NMCA organizations, CPB funding provided about 60% of its total budget, according to Francene Blythe-Lewis. More “right sizing” could be needed, she said, but for now Vision Maker’s staff of nine is able to continue supporting the current slate of about 26 programs and maintain two initiatives, the Native Youth Media Project and the Creative Shorts Fellowship.

Each of the 574 federally recognized Native American tribes in the U.S. have their own rhythm, style and structure to documentary filmmaking, Blythe-Lewis said. Those distinctions aren’t often recognized or respected by media organizations that lack the experience and knowledge of working with Native Americans and Indigenous groups. She worries about a future where funding opportunities for Native American films don’t exist.

“One of the things I’ve heard filmmakers say is ‘Vision Maker Media understands our voice, … knows our history, … understands our perspectives in our own way of telling the story and defends us,’” she said. “Hollywood won’t do that. That’s another real concern.”

“What we see in commercial television, a lot of it is sensationalized, showing the more negative aspect of Native culture and people and lives and communities.”

In July, Blythe-Lewis began speaking with national and local news organizations about how the rescission would affect the public media organizations that serve Native communities. She’s pleased to see growing awareness of Vision Maker’s importance to Indigenous groups and America at large. Now she looks to convert that awareness into more funding. But she recognizes it won’t be easy.

“Our filmmakers are all asking me, ‘What’s Vision Maker going to do? What’s happening?’ We’re struggling to figure it out,” she said. “These filmmakers are consequently left out of the spectrum all the time, and that’s our greatest fear, that they’ll become even more invisible than ever before.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that the Center for Asian American Media had put its capital campaign on hold. CAAM has not put the campaign on hold.