How NPR escaped a financial crisis with help from friends in high places

April Simpson / Current

In his new book On Air: The Triumph and Tumult of NPR, journalist Steve Oney recounts the network’s evolution from a scruffy newcomer into a major force in American media. Dishy, engaging and extensively sourced, the book spans goes deep on the personalities, conflicts and defining moments in NPR’s history. In the prologue, excerpted here, Oney explores a pivotal night when NPR narrowly avoided financial implosion, thanks to a lifeline from CPB.

On the evening of July 27, 1983, a Jeep Cherokee stopped outside the Washington, DC, offices of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the agency that regulates National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Upstairs, the CPB board was holding an emergency meeting to determine the fate of NPR, which after thirteen years of existence had entered a financial tailspin. With $20,000 in the bank and $9.1 million in debt, the network was near collapse. It might not last through the next day.

The men in the Jeep—Congressman Tim Wirth, a Democrat from Colorado and chairman of the House Telecommunications Subcommittee, and David Aylward, his chief legislative counsel—hoped to charm their way into the meeting. “I took over a couple cases of beer,” Wirth said later. The two believed that a few drinks might lighten the mood during what they knew would be a contentious session, allowing them to influence the outcome in National Public Radio’s favor.

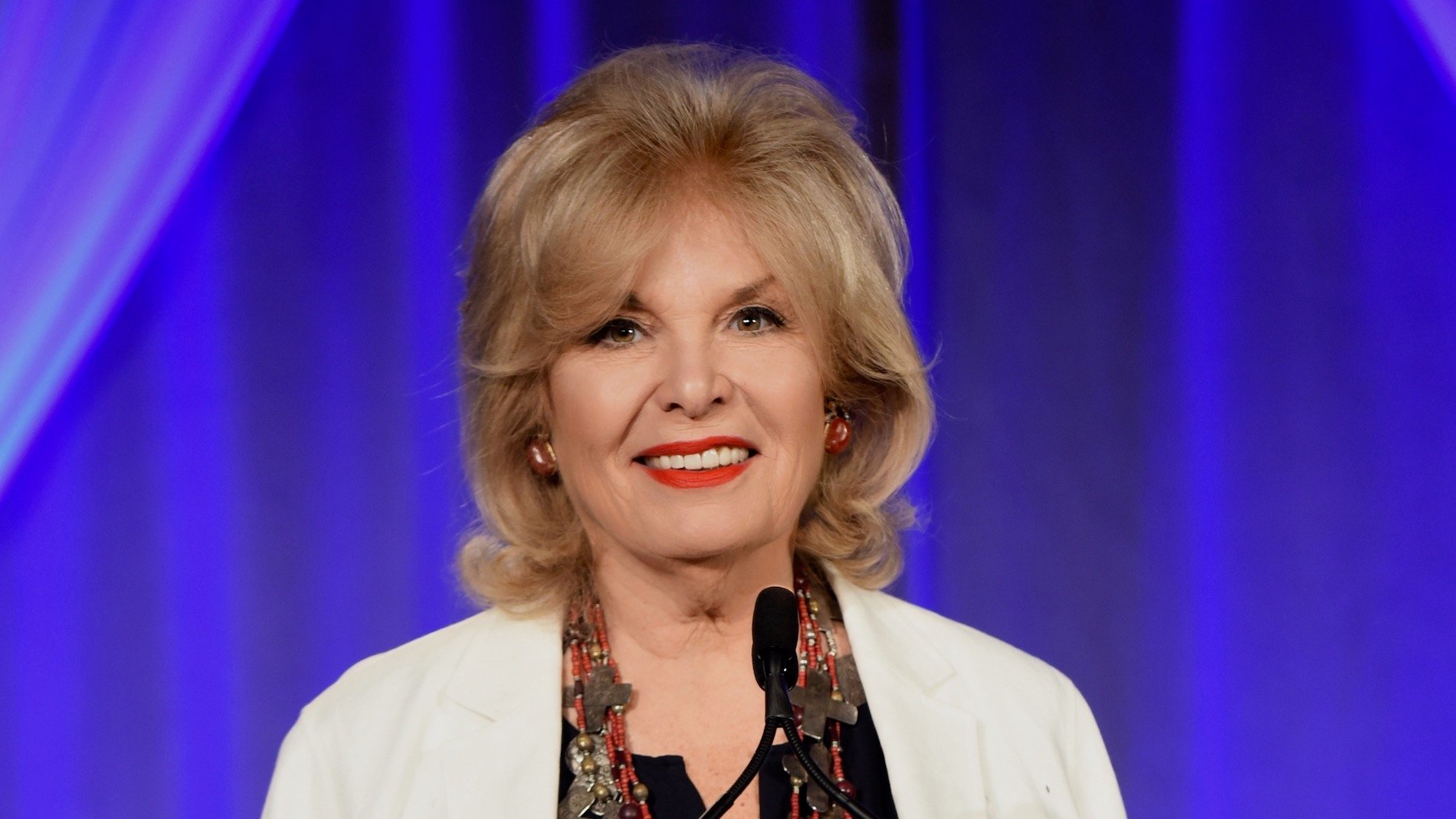

Sharon Rockefeller, chairman of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, believed that any such involvement would be inappropriate. “Sharon met us on the sidewalk and implored us not to come up,” recalled Aylward.

“We don’t have much to do tonight,” replied Wirth. “So, we’re just gonna sit out here and drink.”

The congressman and his aide returned to the Jeep. As eight o’clock became ten, then eleven, they got smashed. “Drinking beer and smoking Merit cigarettes on Sixteenth Street,” Aylward said later. “We were both crazy.” Crazy, however, had little to do with it. Wirth was in possession of a Motorola DynaTAC, the first commercially available cell phone. About the size of a brick and priced at $3,995, the device enabled the men to do something that even a year prior would have been impossible—dial into a closed-door meeting from their car. Every hour or so, Wirth called upstairs.

The attendees at the session sat around a table in the CPB’s sixth-floor conference room. At one end was Rockefeller, various agency vice presidents, and their general counsel. At the other, NPR chairman Don Mullally, his team, and their lawyers. The back-and-forth was as ugly as Wirth had feared. “It was like a union negotiation,” one of the NPR executives said later. “They’d walk out. Then we’d walk out.” The only respites came when a phone atop a credenza on a far wall lit up. Rockefeller would take the call. It would be Wirth telling her, “You’ve got to settle this.”

That a five-term congressman—a future United States senator—was jaw-boning a federal agency on behalf of near-insolvent National Public Radio was the result of a desperate, ethically dubious undertaking by three of the network’s most influential reporters. Known at NPR’s M Street Washington headquarters as “the troika,” Linda Wertheimer, Cokie Roberts, and Nina Totenberg had for weeks been trying to persuade the officials they covered as journalists to intercede with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting on the network’s behalf. “Cokie and Linda each called two or three times,” Aylward said later. “I remember standing in my kitchen near Chevy Chase Circle talking to them about what was going on.” (Totenberg, NPR’s legal affairs correspondent, worked indirectly. “I never talked to anybody on the Hill,” she recalled. “Anything I did I got somebody else to do.”) According to Aylward, the women believed “that the CPB held all the cards” and that the contingent from NPR conducting the negotiations was “overmatched.” The troika feared that in exchange for bailing out the network, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting would restrict its journalistic independence, which would be intolerable. It would be the end of NPR. “Lots of people had roles. Lots of people did things,” Wertheimer said later. “I sensed the urgency,” recalled Wirth.

Since its broadcast debut in 1971, National Public Radio had become a major part of the American media landscape. Its two premier programs—All Things Considered and Morning Edition—aired on more than two hundred stations nationwide and reached millions of listeners daily. Susan Stamberg and Bob Edwards, the shows’ hosts, were well known across the country, possessing a celebrity on par with their network television counterparts. The same could be said for many NPR reporters—not just Wertheimer, Roberts, and Totenberg, but Scott Simon in Chicago and Robert Siegel in London—and a roster of eccentric commentators, among them Kim Williams, Vertamae Grosvenor, and Andrei Codrescu. What set public radio apart was its approach to journalism. Unlike most commercial outlets, it presented the events of the day with depth and flair, taking the time to provide context. The storytelling was innovative, sometimes inspired. Not that NPR was flawless. Occasionally, its efforts were so earnest that they provoked parody or so liberal that they drew conservative ire. Regardless, in its decade-plus on the air, the network had established a sound that imaginatively conveyed the times and suggested that radio—the aging and often-overlooked progenitor of electronic mass communications—might eventually lead a journalistic revolution. With its emphasis on well-produced, character-driven dispatches that brought issues to life and highlighted the human voice, NPR was at the forefront of new ideas about broadcasting. Compared with TV news, which with few exceptions was in a glossy rut, the network was adventurous. First, however, it had to survive.

National Public Radio’s financial woes had been nearly two years in the making, but they’d become known only in the spring of 1983. Frank Mankiewicz, former press secretary to the late Robert F. Kennedy and from 1977 to 1983 president of NPR, had taken the network to great heights, then driven it into the ground. In an attempt to position NPR at the forefront of the dawning digital age, he made multiple risky investments. His efforts to develop online delivery systems that could tap new sources of income were ahead of their times and, on some level, warranted. Republican president Ronald Reagan was demanding devasting budget cuts for public radio. But Mankiewicz’s actions were scattershot, their execution bungled. Auditors had only started to examine NPR’s books, and they’d already found that since the first months of 1983, the network had stiffed its landlord, its utilities providers, and the bulk of its freelance contributors. Worse, during the same period NPR had not deducted federal payroll taxes from the salaries of its hundreds of employees, putting it in arrears to the IRS. The situation was so bad that even some of the network’s biggest supporters were ready to give up. Jack Mitchell, the original newscaster on All Things Considered and part of a group of radio veterans who came to Washington to institute austerity measures at NPR, recalled thinking, “It deserves to die.”

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting was National Public Radio’s court of last resort. Although Ronald Bornstein, Frank Mankiewicz’s replacement, had already secured a $1 million bank loan for the network, it barely covered operating expenses. The only remaining option was a government bailout, but the relationship between NPR and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting was strained. Mankiewicz and Sharon Rockefeller had long been at odds. Each was the scion of a powerful family—the screenwriter father of the deposed network president had written Citizen Kane; the father of the CPB’s boss was Illinois senator Charles Percy, and her husband, one of America’s richest men, was governor of West Virginia. But pedigree was all the two had in common. Mankiewicz regarded Rockefeller as an uptight snob. She “didn’t care about radio,” he said later, adding that she was overly enamored of more glamorous public television. Rockefeller regarded Mankiewicz as a Hollywood blowhard. When she backed increasing the broadcast time of a favorite PBS news show, The MacNeil/Lehrer Report, from a half hour to an hour, the NPR chief, in a comment mocking what he regarded as the show’s self-importance, cracked, “I thought it already was an hour.” Mankiewicz enjoyed taunting Rockefeller. Likewise, Rockefeller wasn’t shy about putting her nemesis in his place. Under Mankiewicz, she told the press when news of NPR’s financial troubles broke, “there was gross mismanagement and lack of management direction. There were unrealistic expectations of the amount of revenues and few financial controls.”

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting board made plain that it would not provide National Public Radio the funding it needed without securing radical concessions. First, the network would have to cut its $26 million annual budget by $10 million—the approximate amount of its debt. Second, NPR’s clients—its member stations—would be required to cosign any note, making themselves financially liable if the network defaulted. Third, NPR would have to alter its business model. Since the network’s founding in 1970, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had given it yearly grants that funded the programming it produced in Washington and transmitted to stations nationwide. Now the agency wanted to give the money directly to the stations, allowing them to buy shows not only from NPR but also from public radio outlets in cities such as Boston (WGBH) and Saint Paul (Minnesota Public Radio). Overnight, the stations would be in competition with the network. Finally, NPR would be forced to cede ownership of its instrument of distribution—space on the Westar IV satellite that beamed its programs around the country. The board “wanted control of the satellite, so NPR couldn’t mismanage” it, too, said Linda Dorian, a lawyer for the agency. It was drastic, but Mankiewicz’s profligacy demanded no less a price.

National Public Radio was not without leverage. As Bornstein later put it, “NPR was the gold standard,” and as the night of July 27 became the morning of July 28, he informed the Corporation for Public Broadcasting board that if the network went out of business, he would work to assure that Rockefeller’s agency was blamed for killing it. When All Things Considered and Morning Edition fell silent, when the voices of Stamberg and Edwards disappeared from the airwaves, the world would learn that the CPB was the reason. Bornstein was adamant. He would paint the agency’s board members and chairman as heartless bureaucrats who in acceding to a Republican president’s budget cuts had destroyed a source of journalistic excellence. To back up what amounted to an ultimatum, NPR chairman Don Mullally was packing the corporate version of a terrorist bomb. “We hired a law firm to draw up bankruptcy documents,” he recalled, adding, “We told CPB that if we did not get the loan, we were going to liquidate the company—pull the plug.”

The leaders of National Public Radio and the CPB board members were playing a high-stakes game of chicken, and Tim Wirth, at the urging of those NPR reporters who feared their guys lacked what it took to see the game to a successful end, was part of it. Initially, he’d used his calls to Rockefeller to remind her that Congress was watching. “Our intent was to be a hovering presence,” Aylward said later. “NPR was in the room with the authorities, but we were the big brother waiting out on the street. The whole idea was to convey the message, ‘You can beat him up, but don’t beat him up too bad.’”

After midnight, Wirth changed tactics. As Tom Rogers, his chief legal counsel, recalled, the congressman began using his Motorola DynaTAC to give Rockefeller a polite version of what she was hearing from Bornstein and Mullally. If the agency failed to come to NPR’s rescue, it “would not only affect public radio but the CPB.” The chairman of a key House subcommittee intended to help network executives pin the onus on the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and its politically and socially prominent chairman. At one thirty, Wirth and Aylward were still sitting in front of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting building. They had no idea how the negotiations upstairs would turn out, but they weren’t going anywhere. “NPR had become a force—a shining example of what media could be,” said Aylward. Which was why the two kept pounding back bottles of beer while keeping the bulky DynaTAC charged.

From On Air: The Triumph and Tumult of NPR by Steve Oney. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Steve Oney’s Current article provides an interesting back drop and “tease” for the book, which I’m anxious to read. As one of the many RIF’d employees in 1983 and who was producing a popular and Peabody Award winning series in NPR’s Cultural Programming Department at the time, I look forward to seeing if there is any mention in Steve’s book of the near-complete demise of that department as part of the Network’s financial crisis back them. Let us not forget that we in that Cultural wing of NPR at that time (and since the Network’s creation for that matter) were also providing a valuable service to hundreds of the thousands of listeners each week.