Kentucky Public Radio’s recipe for a statewide voter guide success

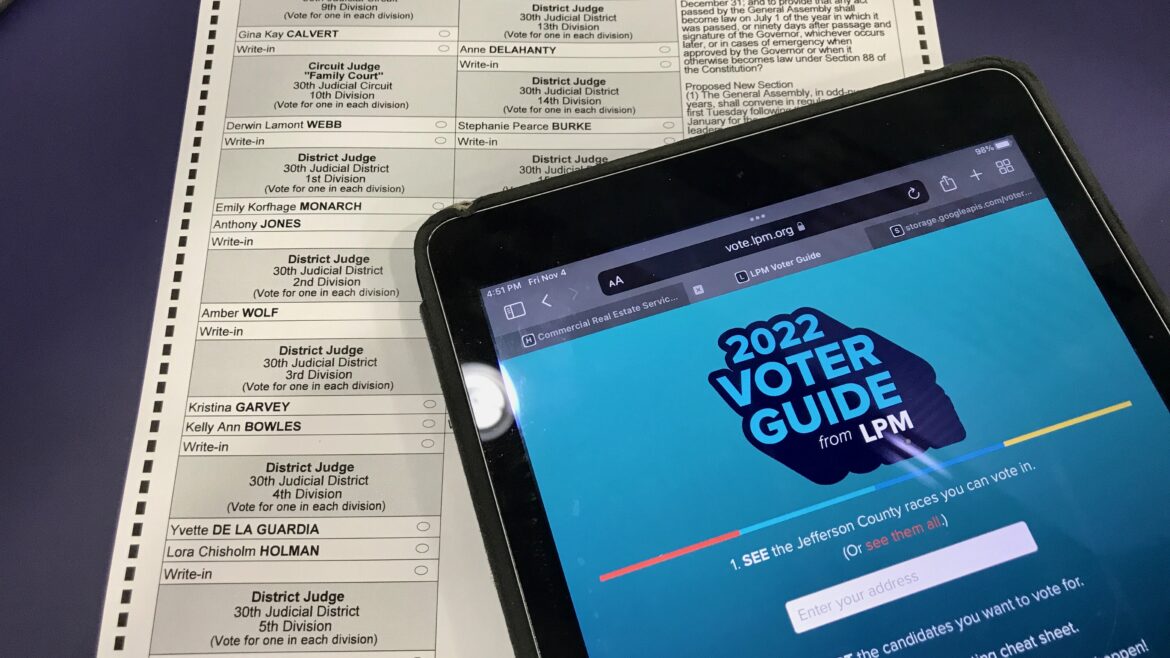

Two years ago, Kentucky Public Radio embarked on an ambitious project to create a personalized voter guide for everyone in the state. As far as we know, we are the only outlet in public media — and rare even in commercial news — that has a web application that geolocates voters and returns nonpartisan profiles of each candidate.

We thought, “The political boundaries are public, digital maps are usually available online, the candidates and county voting plans are public — how hard could it be? Give someone only the information they need.”

Turns out it’s not so easy and does take several months of planning. But the payoff is entirely worth it.

To start, we have to recognize we have a powerful team in our corner. Louisville Public Media and its strong statewide collaboration with WKMS in Murray, WKYU in Bowling Green and WEKU in Richmond provided the know-how and the manpower to execute our lofty idea.

The 2022 general election was the first time we tried this. That year our statewide collaborative editor divided up nearly 300 candidates among reporters from the four stations and asked for journalistic paragraph-length profiles. They profiled races ranging from the U.S. Senate all the way down to local soil and water conservation boards. They were incredibly thorough: Reporters looked up candidates in business records, campaign finance statements and even court records.

We paired those profiles with a little bit of code. A Google Maps tool turned addresses into GPS coordinates and found which political districts the points fell within. With that information, we made only the relevant candidates visible to users. We also let them select candidates in the tool so voters can create their own “cheat sheet” to take to the polls.

It takes a lot of work, but if you’re like us, you’ll see the fruits of that labor pretty quickly. The first year we created a personalized and interactive voter guide, we got about 35,000 unique visits — higher traffic than any other project we published all year.

We’ve learned a lot since that first time and made plenty of adjustments. We stopped including some information, like fundraising totals, and started including more of other information, like endorsements. The code is faster and written so editors can now update candidate info as things develop through a simple Google spreadsheet.

We also started publishing a companion piece each year detailing how we created the guide — which is another great way to promote it.

In the lead-up to the general election this fall, we’ve gotten emails from listeners asking us when we’re going to publish our voter guide. Folks on social media post that they actively search for our guide every election now.

Here’s a brief “recipe” that shows you exactly what we did for our voter guide this year and how you can make your own.

You’ll need to gather:

- A list of candidate filings. (You can usually find this via your secretary of state or board of elections.)

- Digital political boundary maps for all the relevant races you want to cover. You need file types that are .shp or .geojson or something similar. PDFs won’t work for this. You might find these maps on Open Data portals, legislative websites or local municipal portals. If all else fails, search ArcGIS. It’s the most common platform governments use for mapping.

- A team of great reporters and an editor or two willing to spend a bit of time researching each candidate.

- A team member who knows a little bit about coding languages like HTML, CSS and Javascript, or is willing to learn a bit.

Editors:

- Start planning early — probably a month or two before the election.

- Using email addresses and/or physical mailing addresses, send a message to candidates with a Google survey. This will help your reporters in researching candidates. Ask them for a short description of their main stances and endorsements. Optionally, you can ask them to upload a headshot if you want to include those in your voter guide, too.

- Divvy up the candidates you want to profile among your team of reporters. Try not to overload any one reporter and, if you can, keep in mind that reporters will want to profile candidates in their region.

- Edit and organize all this information and, if you have multiple editors, determine how to split up the work editing profiles as reporters submit them. We used a spreadsheet to collect the information and tagged editors to assign edits.

Reporters:

- When your editor assigns you candidates, start researching them. Check court records, business records, campaign finance records (federal and state), voter registration, social media — anything you can think of.

- Consider calling and interviewing candidates, especially if they didn’t respond to the survey request.

- Write a short, paragraph-length profile that sums up the information you found about the candidate that a voter might find helpful. Prioritize statements that show what a candidate plans to do in office or any past experience or instances that might be relevant to the position they’re seeking.

Your mapping or coding person:

- Host all the relevant maps in a mapping service like Mapbox or ArcGIS that has a built-in ability to query the location of a point and return the result with an API. (If your station has university ties, there’s a great chance it already pays for an ArcGIS license.) You can also use this Javascript library, but it’s a little slower and means you’d have to host the maps on your own.

- Pick an API service that can turn a user’s address into a latitude and longitude coordinate. ArcGIS, Mapbox and Google are some great options and have a generous free tier or cost literally pennies.

- Work with editors to decide the best way to parse the candidate information into data. I recommend hosting your edited candidate information in a spreadsheet that editors are familiar with and then using a bit of Javascript to turn it into a JSON dictionary.

- With a little bit of code, you can get users to enter an address, convert it into coordinates, feed that into your map query service to spit out the correct political districts, and then match those to the appropriate candidates in the edited dataset.

- Consider how your application will work in your content publishing platform. Like many NPR stations, all the Kentucky Public Radio stations use Grove. When sharing the guide across multiple stations, we found it easier to host the application as a website on a server and then embed it as an iframe, the same way you might embed media like videos in an article.

Even after all this, will the reviews all be glowing? Of course not. This is digital media on the internet, after all. Is our voter guide flawless and our process perfect? Nope. We still find bugs in it and make edits as candidates change right up until Election Day. We find the profiling and editing process to be time-consuming and, at times, it feels like a tangled mess.

But it’s clear: The time and effort is worth it. Our audience has taken notice. Voter guides aren’t just an election chore. They’re an important way to engage your audience and provide them the information they need to participate in democracy.

Justin Hicks is the data reporter for Kentucky Public Radio and Louisville Public Media. Each election, he works with reporters and editors across the state to create an interactive voter guide.

Bravo