How KUER’s new station fills a media gap for Utah Latinos

Annie Frazier / PBS Utah

Harper Howe (left), an education intern at PBS Utah, and Avanza PD Edgar Zuniga meet Aug. 23 with visitors to Partners in the Park, a summer program to connect residents on the west side of Salt Lake County to programs offered by the University of Utah.

Jennifer Tarazon listens to Spanish music and watches Spanish TV shows but consumes news in English. Without a bilingual media outlet in her home of Salt Lake City, she says, “there’s been something that’s been lacking.”

Last October, KUER in Salt Lake City announced it would launch a bilingual radio station to fill a gap for locals like Tarazon. The 42-year-old grew up in East Los Angeles. Her family immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico.

Tarazon says she didn’t speak English when she started school and “never saw a non-Latino in person. It was very rare. I thought white people were only on TV.” She recalls that she “learned a lot of English from watching Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers.”

Claudia Loayza, also a resident of Salt Lake City, was raised locally by her mother, who moved from Mexico, and her Argentinian stepfather. She says she “grew up listening to NPR and KUER as a backseat listener” because her parents used radio to improve their English.

The 27-year-old Loayza says she also “craves” another media option. “Being very much Latina, but also being very much American, and being very much bilingual, I was only ever offered these kind of monolingual, monocultural spaces growing up,” she says.

Tarazon is vice chair of the PBS Utah Advisory Board, and Loayza is a member of KUER’s advisory board. With the guidance of these boards, KUER and PBS Utah, supported by the University of Utah, bought the license for KCPW (formerly owned by Wasatch Public Media) to create a bilingual media outlet. Since February the frequency, now KUUB, has been airing Radio Bilingüe. The station’s new format will formally launch in March 2025.

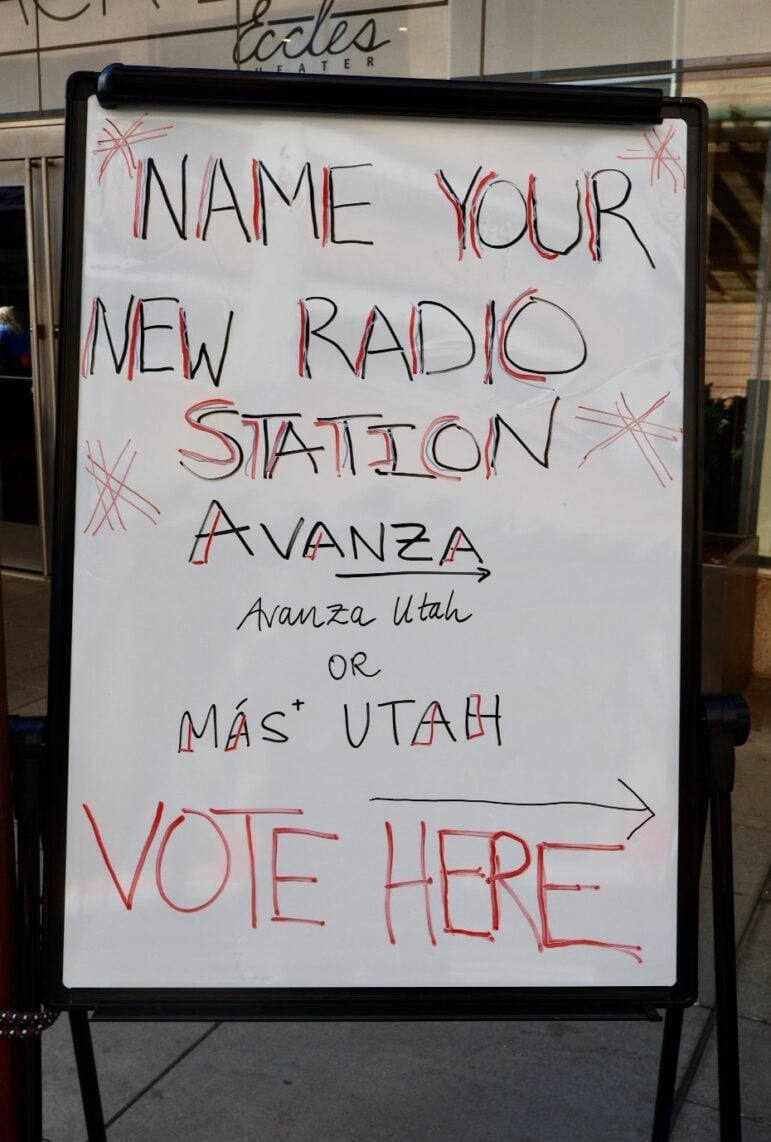

Station leadership asked local Hispanic residents to help name the station, first by submitting suggestions, then voting on a favorite. In September, they announced the new name, Avanza 88.3. “Avanza” means “move forward” in Spanish.

The goal “is to be not only a radio station but a community resource,” says Program Manager Edgar Zuniga, who joined the station in July and was raised in Salt Lake City by Colombian parents. “There is a growing Latino population here, close to 18%, but there aren’t enough media outlets serving us, so KUUB will be a unique addition.”

“This idea did not come out of a sense that this would be a virtuous activity,” says Maria O’Mara, executive director of KUER and PBS Utah. For her, it’s based on an existential question: “I see it as being a really critical part of our success moving forward.”

The ‘power of broadcast’

According to U.S. Census data, 42 million Americans — 13% of the population — speak Spanish at home. Hispanics accounted for almost 71% of the growth of the U.S. population from 2022–23, driven primarily by births. In Utah, Latinos accounted for 49% of the state’s population increase over that same period. Almost 20% of Salt Lake County residents identify as Hispanic or Latino, the highest percentage in the state.

Furthermore, Nielsen reports that Hispanics are avid radio listeners, with the medium reaching 94% of adults. Rossina Lake, founder of RC2 Communications and a member of KUER’s advisory board, says “radio is still a constant” for Latinos, adding that “they listen to radio as they work.”

For Latino audiences, “it’s hard to beat the power of broadcast,” says Ernesto Aguilar, executive director of radio programming and content diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives at KQED in San Francisco, who has been informally advising KUER on the creation of Avanza. “It still has this legitimacy to even teenagers that YouTube just doesn’t have.”

Yet little bilingual public media content is available in Utah. Radio Bilingüe, a nonprofit public radio network that broadcasts primarily in Spanish, distributes shows to 100 outlets in the U.S. and Mexico. But Avanza’s leaders are exploring other content to target younger listeners who speak a mix of English and Spanish.

During this initial phase, they’re listening to the community’s needs before deciding on a permanent format. They’ve determined that millennial Latinos represent the biggest opportunity because they are underserved in the media, are influencers in their families and social networks, and have growing financial sway.

Ultimately, Avanza’s ability to attract this demographic will be a test for the wider public radio system, linking two key imperatives: sustainability and diversity.

“They’re starting from the ground up, creating something brand new and creating a new relationship with the community,” Aguilar says. “I think it’s going to really set this whole thing apart.”

A ‘fundamental disconnect’

The demographic shift happening across the nation is acutely noticeable in Salt Lake City, O’Mara says. She lives on the west side of Salt Lake Valley, which has a quickly growing Latino population, and says she feels “a fundamental disconnect between the community that I happen to live in and what I kind of see as our current audience.”

Years ago, she remembers, a board member asked, “You have a growing Latino audience. What are you doing for them specifically?” When KCPW became available, O’Mara says she and the board wondered “what we would do with a second license in Salt Lake County,” so “those two ideas kind of merged together.”

Tarazon believes radio will help build community, especially since the population has evolved in Utah. Young Latino-American professionals “don’t know where to gather or find their people,” she says. “When you’re in L.A. or D.C., it’s really easy to find that. And I think the radio station is going to really help bring a lot of identity around that group.”

“The most populated age for Latinos in the U.S. is 13 years old,” she says. “The most populated age for non-Latinos is 62. So what does that mean for us as a country, as a state, as Salt Lake City?”

The creation of Avanza provides “a great opportunity to look at this population a little bit differently and start engaging them now, because … we are very loyal to brands,” Tarazon says. As an example, she calls Toyota a “brand of the Latino community,” adding, “When an organization invests in the Hispanic community, we tend to take notice.”

Aguilar also recognizes the economic opportunity, citing large commercial media companies. “Netflix is trying to get into this,” he says. “Hulu and ESPN are trying to figure out ways to serve Latino audiences, particularly bilingual audiences, in a way they might not have done 10 years ago.”

“The team in Salt Lake City understands that this is an opportunity for public media,” he adds.

Station leaders say they believe that dedication and focused collaboration are required to properly address the community’s needs. “We have got to stop making not just programming about an underrepresented community, not even programming for an underrepresented community,” O’Mara says. “We have to start thinking about making programming with an underrepresented community.”

Millennial Latinos bridge the language barrier

Avanza management has narrowed the target audience to millennials, Zuniga says, because research revealed that the demographic has the biggest media needs. Most Latino millennials are bicultural and bilingual, “navigating two languages and two cultures,” he says, and Utah media outlets are underserving them.

Millennials are also “the most natural bridge in connecting the diverse Latino communities … whether that’s older immigrants who maybe don’t speak English as well or younger Gen Z Latinos who may not speak Spanish,” Zuniga says.

Hispanic millennials also commonly speak Spanglish, which the station will use as well. “By being bilingual and not shying away from Spanglish … it’ll resonate,” Zuniga says. “It’ll be authentic. It’s not really authentic for most U.S. Latinos to speak in English and Spanish separately, in silos.”

Now that the station has identified the target audience, it’s homing in on the content. Leaders conducted focus groups targeting three primary age groups — Generation X, millennials and Generation Z. The groups highlighted preferences among the young Hispanic groups that may differ from what traditional public media usually offers.

“It is important to recognize that if you’re serving a new audience, you have to be open to what ‘new’ means,” O’Mara says. “I don’t know if the audience we’re after wants All Things Considered in Spanish.”

Among the target audience, “there’s a lot of news fatigue,” Zuniga says. The focus groups found that millennials “are drawn to a mix of entertainment and informative content that addresses social issues, technology, and personal development,” according to an analysis conducted by Lake. So Avanza’s content will steer away from hard news, at least initially.

Zuniga says the station is planning a community affairs show, its schedule yet to be determined, “where we can dissect what’s happening, but not in a headline format.” As an example, he says, millennial Latinos want to drill down on topics such as “navigating life as a first-gen parent, where you’re not an immigrant parent but you’re also not a mainstream American parent.”

Broadcasts and community events will also focus on health care and, in particular, mental health in the Latino community. Lake says that mental health was a main concern brought up in focus groups, “especially in younger generations.”

Overall, Zuniga envisions an informal tone for the discussions, “kind of like a living room where we can exchange experiences and ideas and profile people doing great things in the community, or resources that are out there for Latinos in the state.”

Focus group participants also expressed a desire to hear new kinds of music. An Argentinian participant said they can listen to music from Argentina online, “but if I can just turn my radio here in the U.S., and I am like, ‘Oh, this is what young people are listening to today’ … but not just pop, folkloric music, like cultural music … I think it would be really, really cool,” they said. “I will listen to that radio.”

Whereas commercial stations typically offer reggaeton or Mexican music, Zuniga says Avanza could include indie and up-and-coming artists, as well as classics from different Latino genres. It may emulate the CPB-funded Urban Alternative stations that target communities traditionally underserved by public radio. The format has been able to reach listeners through a mix of music and cultural issues, “creating a sense of community and really giving context,” Zuniga says. Featuring music will also help keep costs down, tempering the high price tag of producing local news.

Ernesto Aguilar agrees that music is important for Avanza. “Music is the table centerpiece, but what this is about is bringing people to the table, bringing people to sit down with you, to talk, to get to know you, get to know your vision for the community,” he says.

It’s “strategically a very smart place to begin” to build trust, he says. “Once people come to the table and they understand, ‘Oh, this is a table I can get things from and learn things from, and this makes me happier and makes me a better person, or more informed person, or the smartest person among my friends,’ people remember those things, and it’s going to be, I think, very successful,” Aguilar says.

Loayza says she also believes that music will be more welcoming for the desired audience. “My experience being Latina, it’s hardly ever where we can just get straight down to business,” she says. “We always need something to warm ourselves up, whether it’s food or music or talking about our families. It’s just a human connection thing.”

‘We go at the pace of community trust’

Using music to attract Latino audiences to public radio is not new. Radio Bilingüe built a loyal following by programming blocks of Latino music. “We use music to attract, then we use small PSA-type modules of 30 seconds to a minute to provide information,” says Radio Bilingüe co-founder Hugo Morales. The network also produces two daily talk programs, Comunidad Alerta and Linea Abierta.

The block format is useful because the Hispanic audience is diverse, Morales says. “We’re separated by unique languages and histories and cultural traditions,” he says. “That’s what shapes our music.” The network airs Indigenous music Sundays because it’s the audience’s “only day of rest, if they have a day of rest,” he says.

As advice for the new bilingual station, Morales says to let “the voices of the community speak to whatever extent they can.”

Avanza leadership believes that self-determination is key to the station’s success. Zuniga says the more they focus on the community, “the better we’ll serve them, and the more we’ll be able to grow our audiences and our donors.”

Loayza references an African proverb: “When we want to go fast, we go alone, but we want to go together, we go slower.”

“We go at the pace of community trust in public radio,” she says.

Building that trust is imperative before asking the listeners for financial support. “I don’t think we’ll launch membership right out of the gate,” O’Mara says. “I don’t feel like we will have established the kind of trust that allows you to do that. That means we’re going to the philanthropic community, even to the business community for business sponsorship, and to our university. We’re going to be going to … CPB and others to say, ‘We can’t deliver you this audience yet, but we believe in this idea. Can you support us initially?’”

As a program manager with roots in the city, Zuniga anticipates the strategy will work. “I do see the need, and I do see the excitement around the station, and I do think that we can serve Latino communities here in Utah,” he says. “… I am very hopeful and excited that we can make a difference.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misinterpreted a statement by Rossina Lake. The article initially said, “Rossina Lake, founder of RC2 Communications and a member of KUER’s advisory board, says ‘radio is still a constant’ for Latinos. ‘They listen to radio as they work … especially the millennials.'” Lake said that millennial Latinos listen to podcasts while they work. The quote has been revised to remove the reference to millennials.