How LGBT programs have fared in pubmedia, from ‘American Family’ to today’s challenges

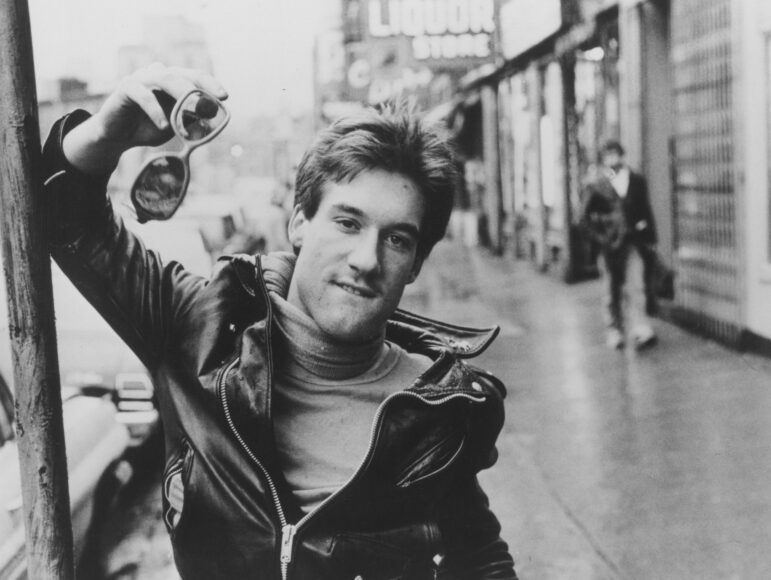

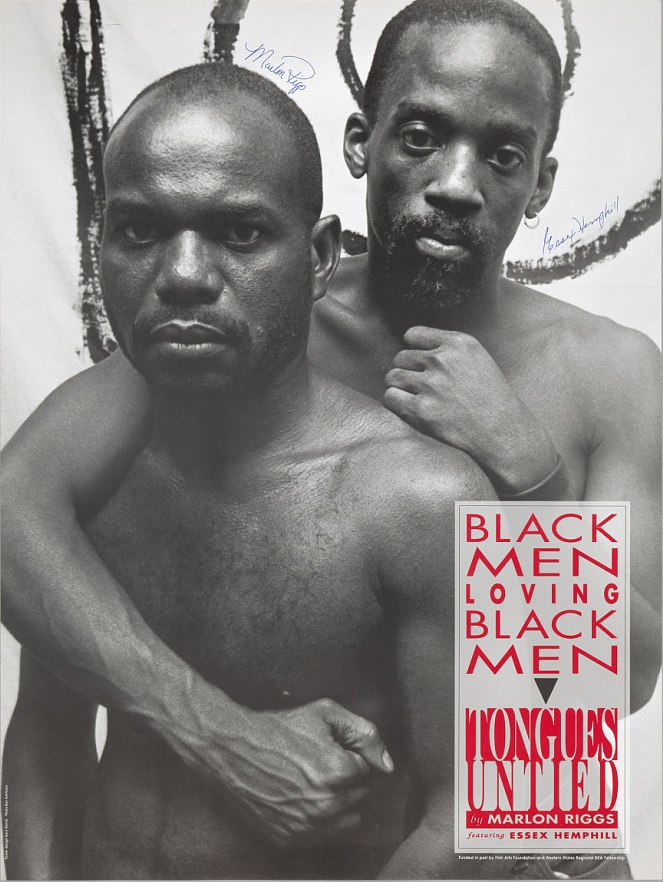

Clockwise from top left: Marlon Riggs and Essex Hemphill of "Tongues Untied"; reporters at the March on Washington; Alison Bechdel in "No Straight Lines"; and Lance Loud of "An American Family." (Loud photo ©1971 WNET)

Public broadcasting gained recognition decades ago for breaking down barriers in the presentation of gay issues in mainstream media. In the ’70s, the pioneering docudrama An American Family introduced viewers to a reluctant gay icon. And in 1991, the broadcast of the film Tongues Untied likely exposed many Americans to their first same-sex kiss on TV.

More recently, public broadcasting’s controversies over LGBT themes have been limited mainly to children’s shows. In 2005, PBS opted not to distribute an episode of Arthur spinoff Postcards from Buster that featured lesbian moms. Dozens of stations carried it regardless.

Just in 2021, Sesame Street added its first two-dad household. Three years earlier, the show had clarified that Bert and Ernie are just “best friends” after Sesame writer Mark Saltzman told Queerty that he had modeled the duo after himself and his partner.

PBS highlights LGBT programming on its website during Pride Month and airs documentaries and other thematic programs during June. Yet public TV has lacked an ongoing national show focused on gay issues since In the Life, the longest-running LGBT show on public media, ended in 2012. Over its 20-year run, the show’s carriage peaked at 125 stations due to opposition and lack of support. Meanwhile, few of public TV’s fictional programs feature an LGBT character.

Documentaries and other programs about LGBT issues can still be found on public TV and local public radio stations. But producers attribute the decline of such programming to the growth of gay representation in other media and a shift in the political climate.

“With few exceptions, it is a risk-averse system, and my sense is that the current leadership would not want to risk that kind of controversy,” said Marc Weiss, who was EP of POV when it presented Tongues Untied. “We’d have to be in a different political and cultural moment for PBS to feel willing to push the envelope.”

The ‘Han Solo of gay people’

In the early days of public broadcasting, programs often referred to the LGBT community in terms of “the homosexual” and only in the context of abuse, deviance or sexual disorders. Multiple episodes of The Criminal Man, a 1950s TV series on KQED in San Francisco, brought up homosexuality in the context of examining why people commit crimes.

Then An American Family and Tongues Untied emerged as groundbreaking examples of gay representation on television. An American Family faced scrutiny for its up-close depiction of the Louds, a California family, in 12 hourlong episodes that aired in 1973. Some critics called the affluent family who lived beyond their means “spoiled” or accused them of heightening drama for the cameras.

Meanwhile, son Lance Loud was developing into a prominent gay figure in the media. His appearance drew criticism. A reviewer for the New York Times described him as an “evil flower” who was “playing in a world of backward genders.” The magazine Commentary called him a natural for television but also deemed him “flamboyant,” saying that he showcased “every theatrical gesture in the stereotyped homosexual repertoire.”

Lance Loud received fan mail from viewers across the country who thanked him for showing that he could be comfortable with himself. Several people said he saved their lives.

According to Lance’s siblings, Lance maintained that he had never been closeted — he was just who he was. In an interview with Current, his brother Grant described Lance as “the Han Solo of gay people” because he was reluctantly drawn into the position of representation.

“He just wanted his life. … It wasn’t like he was avoiding the responsibility,” said Grant, who is EP of a podcast released this year that looks back at An American Family. “It just wasn’t his job.”

Delilah Loud, Lance’s sister, told Current that she recalled her mother defending Lance on The Dick Cavett Show after she was asked what she thought about his homosexuality. “Well, I don’t sleep with my son, so his preference in bed has nothing to do with me,” his mother said.

Delilah said that she and her siblings, who were in the green room at the time, applauded and fell over laughing. Pat embraced Lance and his found family, especially when it came to hosting dinner parties.

“Mom loved a full house,” Delilah said. “She loved interesting people, creative people. She wasn’t intimidated if it was a table of five or 25. Everybody was welcome, and she attributed a lot of her health and vibrancy to the gay community that really enriched her life.”

Lance Loud went on to write for Interview and The Advocate and participated in two PBS updates on the Loud family. In 2001, he died from complications of hepatitis C and HIV.

“Lane was fearless,” Delilah said. “He wasn’t intimidated by any celebrity or larger personality, but he was also very, very loyal to his family.”

A celebration of Black sexuality

While Lance Loud’s TV appearance riled some critics, the 1991 broadcast of Tongues Untied went further, sparking debates in Congress over funding for public broadcasting. Directed by Marlon Riggs, the film explored being Black and gay through surprisingly frank language and imagery. Some stations declined to air it.

The subject matter of Tongues “may not seem earth-shattering now, but then it was just about unheard of,” says Lucia Chappelle, who at the time of the film’s broadcast was producing coverage of LGBT issues and other topics for KPFK, Pacifica’s radio station in Los Angeles.

“Black men talking about loving men was in itself enough to blow out a general audience’s circuits altogether,” Chappelle wrote in an email. “Let alone that it confronted some of the heavier issues of race/sex/class, it was controversial for just featuring Black men being unashamedly out of the closet.”

At the time, “the notion of giving voice to marginalized communities was a core value for the majority of PBS executives,” says filmmaker Vivian Kleiman, a friend of Riggs’ who mentored him in independent filmmaking. “Indeed, the film was broadcast without any bleeps or blurs.”

Marc Weiss recalls that when he asked Riggs whether POV could air Tongues Untied, “he said he’d only be willing to have it shown exactly as he made it — no images obscured, no language bleeped. So we broadcast the film that way. Everything shown on POV has to be approved far ahead of time by PBS programming execs, and this was no exception.”

The passion expressed in Tongues Untied embodied what POV was all about, Weiss said. The series was intended as a platform for communities and movements whose stories were “largely ignored or distorted by mainstream media,” said Weiss, who is now EP of the New York–based Web Lab. “It was meant to be a vibrant celebration of a wide range of voices. Marlon spoke for himself and his community in a way that was immediate and unmediated.”

‘There’s still authenticity’

Public radio has also been home to pioneering coverage of LGBT issues. In April 1988, the show This Way Out debuted on the Public Radio Satellite System. The idea for the show grew from the 1987 March on Washington, where reporters from around the world engaged in “late, late-night discussions where we talked about where we can tell our stories,” says This Way Out CEO Brian DeShazor. The show is still in production and airs on about 200 radio stations worldwide.

Chappelle attended the 1987 rally as an organizer of the broadcast team alongside radio producer Greg Gordon. “That’s when we floated the idea of syndicating a weekly magazine-format show that would be comprised of feature segments from producers from across the country — and the world, if possible,” Chappelle said, who co-founded and co-produced This Way Out with Gordon. “I think there were some 30 LGBTQ journalists at the planning meeting the night before the march, and all were excited about the magazine idea.”

Today, public radio stations are still airing locally produced shows about LGBT issues, including Inside Out LGBT Radio on WPFW in Washington, D.C.; Out FM on WBAI in New York; Gay Spirit Radio on WWUH in Hartford, Conn.; and IMRU on KPFK.

Representation of LGBT issues on public media remains important because “there’s still some authenticity [when it is] produced by LGBT people for LGBT people,” DeShazor says. “It’s also for straight allies and opposing views so that they can learn about our experiences.”

Chappelle argues that as representation of LGBT issues has increased in commercial media, it has become a lower priority in public media — but that shouldn’t be the case. “Why should anybody worry about having a specifically queer space in public media when there’s Rachel Maddow on MSNBC?” she says, explaining the mindset. “It’s kind of like saying that since Obama was elected president, there’s no more racism. That’s a pretty common mistake privileged groups make about dealing with marginalized groups.”

Kleiman believes that concerns about funding are holding back representation of LGBT issues on the national level in public media. “Given that public media depends on public funding, they are obligated to respond to today’s political pressures,” she said. “It would be healthier if they would allow the FCC regulations to serve as the guidepost in such matters.”

With her 2021 film No Straight Lines, which focused on queer comic book artists, Kleiman encountered a reception that differed markedly from the appearance of Tongues Untied on public TV. Presented as part of Independent Lens, the show could have aired unchanged if it were broadcast late at night. But for prime-time broadcast, “national PBS lawyers flagged a list of 69 images in the film that required bleeping or blurring,” Kleiman said in an email. “Some of those prohibited images were mandated by FCC regulations. But the majority were a result of today’s zeitgeist of banned books, censorship and anti-LGBT legislation.”

“I had to cover the word ‘faggot’ in a comic by a queer artist about two queer siblings who call each other ‘faggot’ and ‘dyke,’” Kleiman said. “‘Dyke’ was used 23 times in the comics. In 22 instances, it was okay to see the word in the comics. This one use was considered derogatory, and we had to cover up both ‘faggot’ and ‘queer.’”

No Straight Lines did air on PBS during primetime. Kleiman says it was “courageous” of Independent Lens EP Lois Vossen to include the film in the series. “Indeed, Independent Lens removed the ‘for PBS members only’ access to No Straight Lines for the month of June, in honor of June Pride,” said Kleiman.