How Kartemquin Films and public broadcasting built a legacy of democratic storytelling

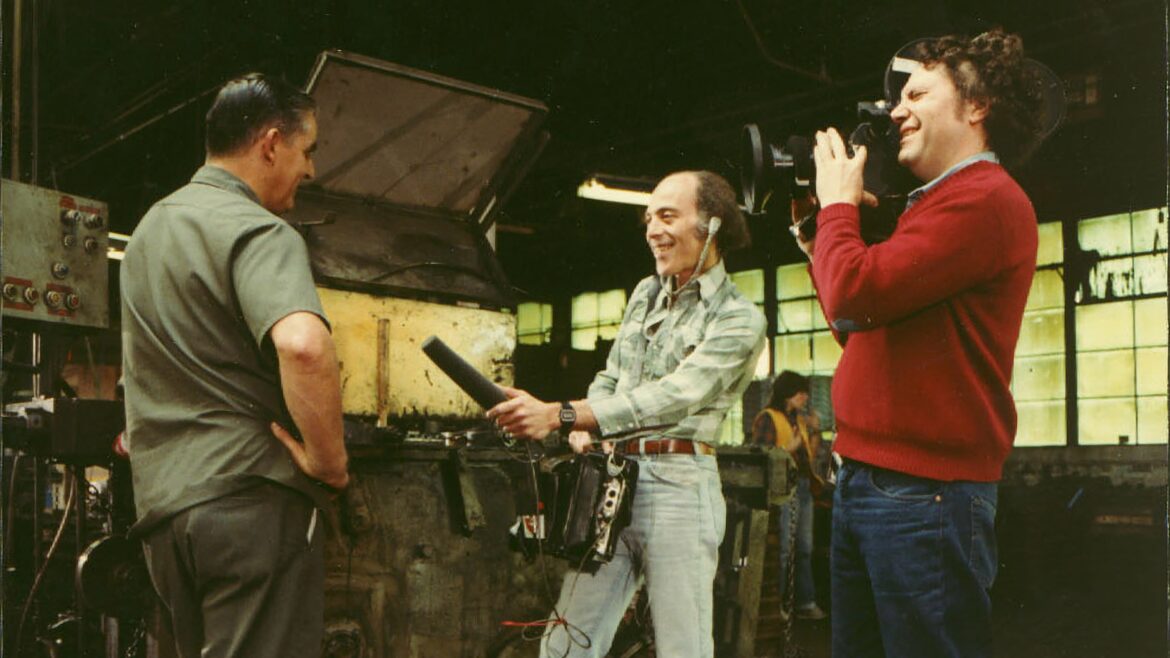

Gordon Quinn and Jerry Blumenthal interview a worker for the film "Taylor Chain II."

In almost six decades of making award-winning documentary films such as Hoop Dreams (1994) and Minding the Gap (2018), Kartemquin Films has been a leader in production. What I didn’t understand until I undertook to tell its history was how essential a partner public broadcasting has been in that journey.

I should have known. Back in 2020, I and other ITVS board members studied how filmmakers relate to public broadcasting in the Center for Media & Social Impact report, Stories for a Stronger Nation: Building a resilient American public with diverse documentary filmmakers and public television. Talking to dozens of them, we found that the documentary filmmaking community was full of people who wanted to use their storytelling power to help build resilience in a democratic culture where too many people didn’t see themselves or their lives on screen. They saw public TV as a natural partner but also saw the obstacles to strengthening that partnership.

Public broadcasters were used to hearing filmmakers complain. But they hadn’t often heard what filmmakers treasured about public TV — which was a lot, and a lot of what public broadcasters treasure about it, too.

Kartemquinites were important in informing that study. But only when I looked back over the decades did I see the two-way relationship Kartemquin had with public TV — and how influential Kartemquin has been in shaping filmmakers’ respect for public TV’s mission.

Big ideas, new institutions

Public TV and Kartemquin were formed almost exactly at the same time. Both were brought into existence with big ideas. The vision of public broadcasting that could be a vital resource for American citizens otherwise stuck in a commercial “vast wasteland” motivated many to work for the 1967 legislation. In the same period, Kartemquin co-founder Gordon Quinn was studying at the University of Chicago, learning both about an exciting new kind of filmmaking, cinéma verité, and about the democratic vision of John Dewey. Dewey, once a U of Chicago professor, had argued that democracy was ultimately defended by the ability of different people to come together around a shared problem, understand its dimensions and leverage their collective power as a public on institutions that could remedy it.

Quinn and his colleagues, especially Jerry Temaner, founded their new company in 1966. They imagined it as a place to make a kind of documentary that would tell closely observed, grassroots stories that could help people form publics for a stronger democracy. They also imagined their own film company as a kind of institutional citizen: of a film community, of a local Chicago community and of a national community.

But even before public TV existed, as a college student Quinn had already been working with educational channel WTTW, producing episodes for its program Student Journal. When his mentor Mike Shea and he completed a priceless profile of Chicago’s vital Maxwell Street market, And This Is Free (1965), Quinn eagerly took it to WTTW — which turned it down.

That wouldn’t be the last time public TV rejected him. In the 1980s, WNET refused to carry The Chicago Maternity Center Story (1976) on its Independent Focus program, overriding curatorial decisions. This film about an at-home maternity service offered an unsparing, feminist critique of commercialized health care. Kartemquin staunchly argued the importance of letting audiences see a point of view, now a feature of many public TV documentaries. At the time, though, this pioneering perspective was still too controversial for WNET.

Allies over the long run

But over the decades public broadcasting would come to be Kartemquin’s most dependable ally, and sometimes its savior. When WTTW began working with Chicago media activists Tom Weinberg and Jaime Cesar to program Image Union, Quinn and other Kartemquinites, as well as Chicago filmmaker Jeff Spitz, fueled the program with their works. When Kartemquin was years into all kinds of debt making a film that had no stars, no happy ending (or any ending, it seemed), and was set in the poor-but-proud Black neighborhoods of Chicago, the Minneapolis station (then KTCA) came in with crucial funding that kept the project Hoop Dreams alive.

When funding from the arts organization Ravinia fell apart for a film about the legendary Bill T. Jones — one that took an uncompromising look at American racism — ITVS and American Masters saved A Good Man (2014). When Minding the Gap was caught between the access Hulu could offer and its obligations to public broadcasting, PBS worked with Kartemquin on a creative and ultimately successful solution. When because of political gridlock, the Illinois state government froze many essential services, Kartemquin and the progressive newspaper In These Times worked with Peoria public TV station WTVP to make Stranded by the State (2017), vignettes about the gridlock’s victims made available both online and on the air.

Kartemquin’s partnership with public TV has been a boon to public broadcasting, as much as to the filmmakers. That KTCA investment in Hoop Dreams may have won the most dazzling rate of return in its history; the station came to control a major stake in a multi–million-dollar, long-term asset. Kartemquin’s immigration series, The New Americans (2003), led to precedent-setting programming innovation when, pre–binge-watching, PBS cleared a path over several days for the whole series to air. The series also spun off modules that spurred improvements to immigration policy and social work practices for those interacting with new immigrants. Research on Kartemquin’s film about homeless teens in Chicago, The Homestretch (2014), showed the power of this film in helping caregivers, social workers and teachers nationwide do their own work better.

Citizen filmmakers

Kartemquin was not only founded to make democratic documentaries but to be an actor in a democracy. Kartemquin was historically the Midwest home of filmmakers’ media activism, which included supporting the creation of media arts centers and public access cable services, staffing panels for the national and state-level endowments for the arts and humanities, participating in the (now bygone) “community ascertainment” processes of local broadcasters, and of course expanding the diversity of voices on public broadcasting.

When media activists including Marc Weiss, joined by visionary producers in public broadcasting such as David Fanning, pushed for serious investment in programming featuring independent voices, Kartemquin supported and provided arguments that linked that argument to public TV’s mission. The result was POV, which has shown many Kartemquin productions. Over a decade between 1978 and 1988, Kartemquin worked in the core leadership that eventually succeeded in winning legislation that created Independent Television Service. Quinn was one of the negotiators with CPB to implement the law. ITVS became a frequent co-producer of Kartemquin films. And when, in 2013 and 2015, the fate of both ITVS’s Independent Lens and POV was at stake on the PBS schedule, Kartemquin was instrumental in making filmmakers nationally aware of what was at stake and to make their voices heard.

The allyship of Kartemquin and public broadcasting has faced challenges, but because of the big ideas behind both institutions, it has endured. As Gordon Quinn at the height of enthusiasm for the “new public square” of social media, public TV “is a unique resource, precisely because it gets government funds, which allows the public to make claims upon it. Whatever possibilities new technologies bring, indies must defend the notion that one of those public voices, which will be different from the others, must be publicly funded. One of the functions of public media is that it often keeps other voices honest.”

Kartemquin’s long history could not be told without its evolving partnership with public TV, and it is yet one more reminder to both American independent filmmakers and public broadcasting executives that ideas matter, and that there is a relationship between these institutions and the project of democracy itself.

Patricia Aufderheide is University Professor in the School of Communication at American University and a board member of the Independent Television Service. Her latest book is Kartemquin Films: Documentaries on the Frontlines of Democracy (University of California Press, September 2024).