Why public media needs to let younger decision-makers call the shots

Courtesy of Evan Shapiro

Shapiro, a media analyst and professor at New York University and Fordham, is known for his "media universe map" that explains the size of various media and technology conglomerates.

Evan Shapiro, an adjunct professor of media and entertainment at New York University’s Stern School of Business, has a message public TV leaders need to hear: Public media is in danger of falling further behind as the media ecosystem adapts to the “on-demand mindset” of viewers under 40.

Shapiro, who is also an adjunct professor at Fordham University and Substack writer who has claimed the title of “media’s official unofficial cartographer,” has the data to back him up.

YouTube, the Google-owned company, made up nearly 10% of all viewership on connected and traditional televisions in the U.S. in June, according to Nielsen. This means millennials and younger audiences are increasingly more likely to discover public media programs on streaming platforms like YouTube than on PBS or station websites.

Shapiro, a former EVP for NBCUniversal, says public television needs to rethink how it reaches the audiences of tomorrow. But PBS and its stations are not alone in this — they face the same challenges in the new attention economy as other for-profit media conglomerates and public service broadcasters globally.

In an interview with Current, Shapiro discussed why he believes public broadcasting deserves more financial support from the federal government. He also explained why focusing on younger audiences can positively impact public media organizations.

This transcript has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Julian Wyllie, Current: You spoke at the PBS Annual Meeting in May about where PBS and public broadcasting stands in the wider media landscape. What did you want the crowd to take away from your keynote?

Evan Shapiro: My message was this: “Your traditional ecosystem is in dire straits, but the new ecosystem is actually full of benefits and opportunities for you.”

You have to understand what the rules of the road are and operate under this new paradigm. And you have to look for the new PBS users who are just as likely to make a donation. They’re going to do it for different reasons, and they’re going to come to you through different avenues.

If you put those users at the center of your operation in the way that you did with people who would call you on the phone to give you an annual membership fee, then you can do more than just survive. You can thrive. But you really have to retrain the entire enterprise around that.

Current: You said that if you can convince someone to pick up the telephone and donate money on an ongoing basis — like public television stations have done for decades — then you can kind of do anything on the planet Earth.

Shapiro: Yeah, that’s the hardest thing to do, so it is infinitely transferable. But you have to agree that you’re going to transfer it.

We are still in an era of media where the leaders don’t understand that. I’m talking about globally, not just in the United States. They have to agree to shift the culture to a world where YouTube is an equally important part of their broadcast system.

Current: What does that look like for PBS then?

They have PBS Passport for members and the PBS Video app. They have broadcast channels, live linear streams on several platforms, and digital-only content on YouTube. Is it an issue of there not being enough content on larger platforms like YouTube? Should they just focus on that?

Shapiro: There’s two parts to this.

The first is that the audience for PBS, on broadcast, is quite old. These are the most loyal viewers of PBS. They view it primarily live, when it’s on. But that’s not the real issue.

The real issue is that new viewers are on connected televisions, and they don’t have a PBS experience. These are younger Gen Xers, millennials, Gen Zers and even Generation Alpha. They don’t necessarily have PBS muscle memory. They don’t have broadcast muscle memory. When they first turn on a connected television, they have to agree to get to the PBS app, they have to agree to go to the App Store and then they have to download the PBS app.

Just think of the friction in that experience right there. Think about every person under the age of 40 that you know. Then ask yourself, are they likely to download or pre-install the YouTube app or the PBS app? How are they going to discover these shows, on YouTube, with the connected television, or on the PBS app?

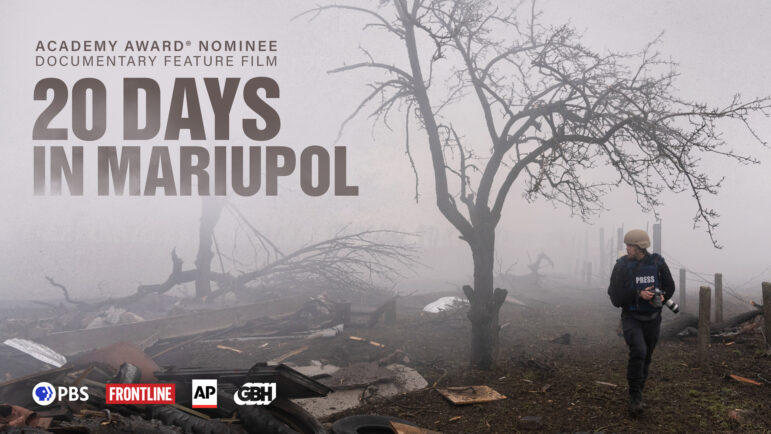

Here’s a great example. Frontline is a PBS property. They won the Academy Award for Best Documentary for 20 Days in Mariupol. If that entire documentary is available on YouTube for free, where do you think most people will discover that, in the PBS app or on YouTube on connected televisions?

Current: They’d be more likely to discover it on YouTube.

Shapiro: Correct. And that’s going to be just as true for shows like Nature and other PBS-branded shows as it is for any other property in this day and age.

The on-demand mindset or search-query mindset of Generations Alpha, Z, Y [millennials] and X is always going to gravitate to the title first and the channel second. That’s true for shows on Netflix or Amazon. But it’s specifically going to be true on connected televisions and on the internet for PBS, whose shows appear on Amazon, YouTube, Netflix and many other platforms. You want to cater to that search mindset.

“You have to lean in to where the consumers are and be prepared to be discovered, however they’re going to discover you. And then it’s up to you to convert them into lifelong members.”

How does the PBS affiliate play into this? It’s a great question. If you look into the big pillars around news and culture, arts and science, children’s programs and everything else PBS is known for, there are definitely local extensions that each affiliate can lean into.

Programs about the local performing arts center, the local civic engagement that’s going on, the local environmental and parks departments, the local zoos and museums — you can bring programs about them to the table. They don’t have to be produced at the same level as Nature or News Hour to be relevant to local constituents. That was part of the message that I was trying to send at the PBS Annual Meeting.

Current: I think younger viewers are more likely to say, “I’m going to YouTube to watch 20 Days in Mariupol” versus “I’m going to watch this Frontline doc.” And then as they get more into Frontline, they may eventually come to that second train of thought. But maybe it’s the first thought that gets them there in the first place.

Shapiro: This reminds me of a conversation I had with a senior public broadcasting executive in the U.K. I sent a very similar message to them at a management conference when I demonstrated how people under the age of 35 in the U.K. did not consider public service media in their mix — dramatically so.

This very senior executive said to me, “We’re worried about attribution. We have found that we get half the attribution on YouTube for our content than we do when it’s in our own environment.”

My response was this: “Half is better than none, isn’t it?”

That’s kind of the crucial message. There are younger generations who just don’t understand what these brands mean. But they do love the content, whether that’s football or political content in the U.K., or documentary, and cultural or news content here in the U.S.

You have to lean into where the consumers are and be prepared to be discovered, however they’re going to discover you. And then it’s up to you to convert them into lifelong members.

Look at Space Time, which is a PBS property. It has 3 million subscribers on YouTube. It doesn’t have that many subscribers on Patreon, but their Patreon is driving $250,000 in revenue every year. That’s what it looks like in the modern era. That’s not terribly different from membership drives. If you go back and you watch Julia Child do those telethons for GBH in Boston, you realize there’s not much difference between the two. It’s just the platform.

Current: Eons is another PBS show that raises money on Patreon. They raise about $11,000 a month. Other programs from PBS stations could go the Patreon route. Maybe it’s supplemental, maybe they don’t get a ton of membership, but it could still help.

Shapiro: Yes, that’s one digital example that leans into the PBS model, which is we’re going to give you content in exchange for your financial support. Is it going to be life changing? No. But is it a way to start to cater to the new membership with the patronage model that younger generations are already embracing? Yes, it is.

Current: I want to see what you think of this. You described one exec’s concerns about how people were going to discover and attribute their content. Is this an example of the generational divide? Younger people today are discovering content in a different way, but that’s what’s normal to them.

You’ve said that younger people need to be in the rooms where those decisions are being made because they represent the post-broadcast world. They understand that we’re not going backward, that we’re not going to put the genie back in the bottle.

Some decision-makers may need to work on losing some of those broadcast muscles to build new media ecosystem muscles, so to speak.

Shapiro: 52% of the American population is under the age of 40. Millennials and Generation Z are the two generations that will wind up spending the most and having the most expendable income in the market. Those are the audiences you want to cater to. In this era, when the user controls their entire suite of services on the remote control in their pocket, you have to put them at the center of everything, including the decision-making process.

You do have to put people in the room who are younger and in the demographic of the majority, which means people under 40. But they also have to come from different economic strata and include people who might not be able to afford every subscription product that’s out there.

An example is the New York Times. Former CEO Mark Thompson, who is no youngster himself, transformed the Times from a family-led advertising-dependent paper product delivered by diesel truck into one of the best digital subscription products on the face of the earth, and he did it in less than a decade.

He has said that the cultural shift was more important than the business model shift. He had to give permission to 20- and 30-something project and product managers to make decisions. They didn’t have to run everything up to the CEO’s office or to the family’s office. That was crucially important.

This is not a PBS problem. This is a Western and perhaps global media conglomerate problem.

Current: I also think of the New York Times as an example of a legacy media property transforming with the times. Can you think of others?

Shapiro: It’s hard to find another.

Current: Could you think of even two?

Shapiro: [Laughs].

Current: [Laughs]. I guess that’s your answer.

Shapiro: The closest I can come up with is both Channel 4 and the BBC. They have done a really excellent job compared to the whole.

At Channel 4, their embrace of YouTube as a distribution platform and way to grow revenue in a difficult advertising economy in the U.K. has been very impressive. CEO Alex Mahon deserves a tremendous amount of credit, despite the criticism she and the organization have gotten for managing through one of the worst economic environments in U.K. television history.

The BBC and Tim Davie also deserve credit for getting out ahead with iPlayer and becoming one of the first to get out there with a purely digital product.

Current: You’ve talked about generational differences between the media preferences of consumers under and over the age of 35. What was the source of that research?

Shapiro: It’s Hub Entertainment Research. They ask consumers about their must-have sources for media. Of the top five, four are through YouTube.

All consumers have an average of around 13.5 media sources. Less than half of those are must-haves. For consumers under the age of 35, if four of those are through YouTube, one of those is going to be Spotify or Netflix. Boom, you’re done.

I don’t care who you are, if you’re in the media business — audio, video, gaming or social — your biggest competitor is YouTube. But no matter how much data I or other people put out there, most media companies still don’t understand that. Netflix doesn’t understand that. And if Netflix doesn’t understand that, it’s kind of excusable that PBS and its local affiliates might not yet understand that.

The secondary part of this is that media companies are not training themselves to compete with YouTube. They’re ultimately going to fall behind long-term because of how much of the audience is going to continue to be driven by [platforms like YouTube]. You know, the Mr. Beasts of the world and the Trixie Mattels of the world and the Logan and Jake Pauls of the world.

It’s odd that Netflix is trying to pay Jake Paul millions of dollars to fight Mike Tyson. Amazon is paying hundreds of millions of dollars to Mr. Beast. But neither really understands the nature of the beast.

To your earlier point, it’s a generational issue inside the upper echelons of the media industrial complex writ large. PBS is a symptom of that. But they are hardly, hardly alone.

Global publishers in media tend to get to new technologies a little late. I don’t think PBS is necessarily lagging behind too much of the rest of corporate media. Just look at Warner Bros. Discovery and how much of a mess they are.

Current: You were an executive VP at NBCUniversal, where you led the comedy-focused streaming service Seeso before it was closed in 2017. You were also SVP of marketing at Court TV in the early 2000s, and president of IFC TV and Sundance Channel. You’re now teaching at NYU and Fordham. How have your past jobs and current teaching experience helped you understand how younger viewers use media?

Shapiro: I’ve always been very, very focused on what the data tells us. If you Google my name and TV intervention, you’ll get an article from 2012 where I basically said some of what was going to happen.

Teaching at NYU and Fordham forces you to retrain your brain every semester so you know more than the users of media who are actually driving the change in the media. To sit in front of a roomful of 18 year-olds who are paying a quarter of $1 million to go to university, you had better know more about their media usage than they do.

The problem for me when I was working in media was that I was always 15 minutes early to a lot of things that were happening. Whether you look at what I tried to do at Sundance Channel or at Seeso, it was always because I felt I knew what was coming.

“In the media landscape, your competitors aren’t each other, it’s Big Tech.”

I was brought in to be the change agent at these companies to a certain extent, but what I found out in many cases is that companies say they want to change, but they don’t really want to change.

When I left the media ecosystem and unfettered myself from the limitations of what I could say out loud amongst people in the industry, that’s when it became clearer that the things I had noticed were truer than I had thought.

The great benefit I have over David Zaslav of Warner Bros. Discovery and Bob Iger of Disney and anybody else who runs media companies is that I don’t have to run a media company. I’m not distracted by the bullshit, the shareholders, the attacks from wannabe proxy board members or the press. I don’t have any of that to distract me. I get to sit and read their earnings reports. So I have a distinct advantage that makes it a lot easier to spot the trends and say, “Hey guys, duh.” It’s like, if all I was was an Instagram model, yeah, my abs would look fantastic.

Current: I agree that the execs have a lot on their plate. But if they can’t have their eyes everywhere, they should trust the people they hired to look 15 minutes ahead.

Shapiro: The problem with the media ecosystem on the planet Earth is that for seven generations, all we’ve done is hire our nieces and nephews. You get confirmation bias, genetic level confirmation bias. You all have the same chin. It’s a real fucking problem. It explains pretty much everything.

Current: In a Deadline article from 2020, you first talked about your media universe map and said that people need to understand that they’re all players in the attention economy. Everyone is just competing for people’s time.

I like that your media universe map includes AI companies like Tencent and Nvidia. You recognize Alphabet having their hands in Google and YouTube, and Microsoft’s businesses in gaming, computing and AI. The media universe is bigger than just people sitting down to listen to NPR or watch something on HBO.

Shapiro: The first part of my premise was that in the media landscape, your competitors aren’t each other, it’s Big Tech.

Secondarily, much like Comcast offers the profits from broadband to fund the television ecosystem, Apple is going to use their revenues from their iPhone to eat your fucking lunch. If you don’t think that’s fair, that’s fine, but it’s still going to happen. Google will use its money from search and other areas. Amazon will use its money from the cloud.

I’ve continually written since then about the rarity of a solo product in media succeeding in the world. Netflix is the only profitable streamer. Spotify, it will get eaten up by either YouTube, Amazon or Apple — or just run out of business at some point. There’s no way that company can go it alone as a stand alone property.

Netflix has a long stretch, as it’s built a long company, but eventually it too will succumb to this multi-pronged universe of the super app.

“The most important thing we can do is support public media as a counterbalance to the craziness that’s happening on planet Earth. Part of the reason we are in a crazy spot is because we have not taken care of our public media as well as we should.”

Current: Your map doesn’t usually include public media outlets because it’s based on calculations of market valuation. And there’s no way to calculate that for public media.

Shapiro: It’s difficult. Do I call the public service media outlet and ask for their own evaluation of their valuations? Who do I go to to value the BBC or PBS, independently? It’s very complicated.

I am working on a map of the U.K. media universe that I’ll release this fall. And that will, I think, for the first time, put everybody next to each other on one map for one region. And then I think I can expand it from there.

Current: If you had to run a public service media outlet, either PBS or NPR, what would you do or what do you think needs to happen?

Shapiro: First and foremost, I think the American government needs a stern talking to by the people who run PBS. They’re still governing themselves by laws and rules written in 1967. One of the first things I would try to do is enlist more public support for changing how the government funds the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and PBS.

PBS is handcuffed by the lack of support it gets. It’s embarrassing. I don’t think you can do as much as you would want to across the public media ecosystem in the United States without really changing the way it’s funded.

Current: Politicians often recommend zeroing out public media’s federal funding. It just happened again with the House Appropriations Committee.

Shapiro: I blame the government. PBS and Sesame Street of all things have been the soccer ball of politicians in D.C. for decades. And I don’t know how you make public service media the enemy, but they have. One has to wonder why they do that. To me, the main reason for that is because a free, vibrant, well used public service media watchdogs the government. And that’s why they don’t want it.

The most important thing we can do is support public media as a counterbalance to the craziness that’s happening on planet Earth. Part of the reason we are in a crazy spot is because we have not taken care of our public media as well as we should. To me, that gets buried in most of the coverage of public media.

Part of my speech at the Annual Meeting is that we need to enlist people my age and younger to get back into public service media, to make it a priority. In a generation, you could change the nature of public service media, the way that a generation of people who live in a single neighborhood can change a school if they all join the PTA, raise money, and put effort and elbow sweat into it. We can make these changes, but we have to decide as members of the public to do that.

Even as a radio snob who doesn’t know all that much about TV, this is incredibly good stuff.

For me, the big thing that Shapiro says that resonates with me was this: “Teaching at NYU and Fordham forces you to retrain your brain every semester so you know more than the users of media who are actually driving the change in the media. To sit in front of a roomful of 18 year-olds who are paying a quarter of $1 million to go to university, you had better know more about their media usage than they do.”

That’s a person who understands *process*. And that process is more important than outcomes when there isn’t yet a definite blueprint for success in an industry.

A person who understands that if you want to stay ahead of the curve when the curve is inherently age-driven, you need to not just be someone interacting with young people. Lots of college professors do that, content to just tell kids about their own experiences and expect the students to translate that to the future on their own. No, Shapiro takes the tact of “I need to be AHEAD of these kids who are already instinctive ahead of everyone else”, and thus is always pushing himself to shed old prejudices and acquire new knowledge on a near-literal daily basis.

That’s a person worth listening to. I may have to break down and finally make an account on substack so I can subscribe to his.

Aaron — I subscribe to his substack and it’s worth it.

I swore a long, long ago that I would never subscribe to substack or medium…but, well, one can’t let dogma get in the way of good sense. :)

PBS Passport streaming is clunky. Hard to find/resume preferred programming. Try locating an archived American Experience episode, e.g.

Headline is clickbait, and implies opinion. Is this an editorial? Article makes some very good points. The bait isn’t really needed. Add to that that NPR’ Maher just confirmed her belief (at PMDMC) that analog radio is still far and away the business driver for pub radio. So a nuanced approach is needed.