With a new documentary, ‘Reading Rainbow’ looks back

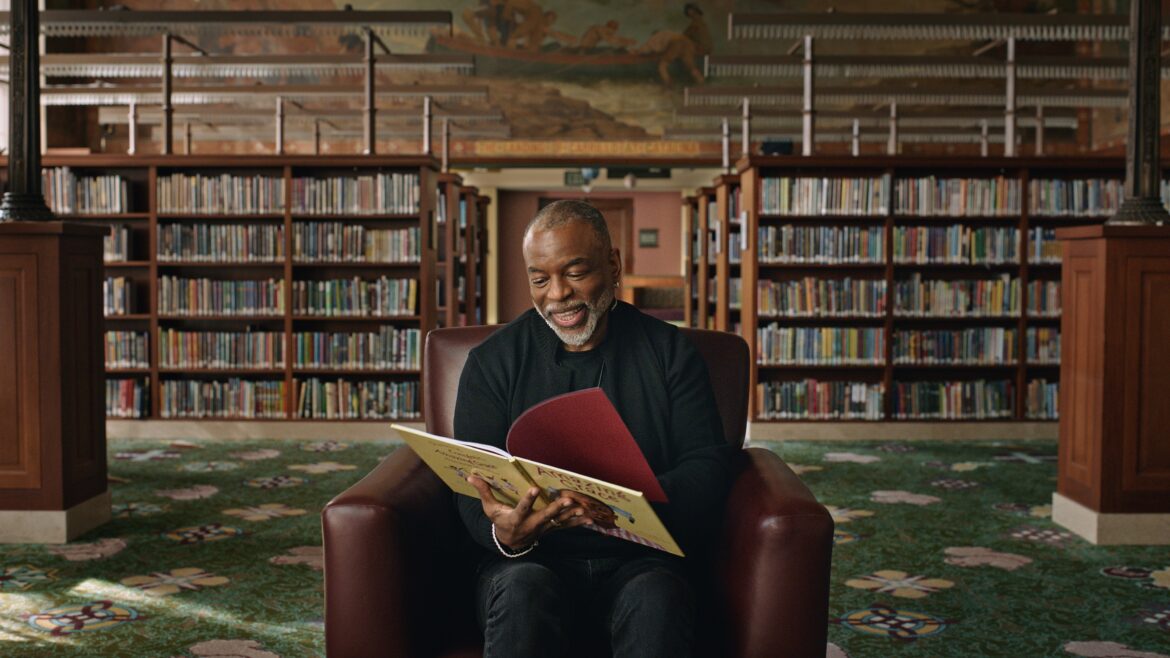

"Reading Rainbow" host LeVar Burton in the documentary "Butterfly in the Sky."

Running for 155 episodes spread over 23 years, Reading Rainbow helped guide generations of kids toward a love of reading. Now, a new documentary about the show is looking back at its creation, development and influence.

Butterfly in the Sky — which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2022 but just hit digital outlets April 30 — was crafted by Brett Whitcomb and Bradford Thomason, the nostalgia-loving directorial team behind GLOW: The Story of the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling, A Life In Waves, and Jasper Mall. Born of the duo’s love for Reading Rainbow as kids, Butterfly features interviews with the show’s creators — Cecily Truett Lancit, Larry Lancit, Twila Liggett and Tony Buttino — as well as host LeVar Burton. Former kids who appeared on the show also pop up, as does composer Steve Horelick, who created the program’s eternally catchy theme song.

Whitcomb says he was shocked no one had ever made a documentary about Reading Rainbow, not just because of what the show meant to so many kids but also due to how little information was available about the show’s decades-long run. In fact, the show’s documentary-style approach to children’s television was part of what made Whitcomb want to become a filmmaker in the ’80s. The director says that getting to see different parts of the world — like the volcano in Hawaii featured both in Rainbow’s “Hill of Fire” episode and in clips in the documentary — helped him develop a passion for global storytelling.

“Werner Herzog made some really great early films that felt almost like nature documentaries, and Reading Rainbow was exploring things in the same way,” Whitcomb says. “They would just get in a van and go make this thing and then come back and start editing, incorporating kids and the books that they were exploring.” That style of work set up camp in Whitcomb’s brain, as did a love for reading, both instilled by watching Reading Rainbow.

The birth of a ‘Rainbow’

A co-production of Nebraska ETV (now Nebraska Public Media) and WNED-TV in Buffalo, N.Y., Reading Rainbow hit the air in July 1983. It would go on to earn 200 broadcast awards, including a Peabody and 26 Emmys — 10 for outstanding children’s series — and becoming the third–longest-running children’s series in PBS history. At the show’s genesis in the early ‘80s, though, it was simply a question: “How do you get kids excited about reading?”

Butterfly in the Sky tells the story of Rainbow’s entire arc, starting with the teaming up of WNED’s Director of Educational Services Tony Buttino and Nebraska ETV’s Twila Liggett, who’d previously been a book-loving elementary school teacher. In the documentary, we learn that Rainbow was born as a response to kids turning away from books and toward television, consuming an average of five hours a day in 1980. Educators had begun to resent the medium, but Buttino and Liggett believed they could use television to motivate children to read, the same way that Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood imparted social emotional growth or Sesame Street taught preschool skills.

Producers Larry Lancit and Cecily Truett Lancit were recruited to join the team, thanks in part to the latter’s work on the PBS series Studio See, which was shot entirely on location. According to Truett Lancit, that show helped give Reading Rainbow its real-world perspective.

Liggett was tasked with fundraising, which didn’t come quickly. Eventually, with funding from CPB, Kellogg’s, WNED and Great Plains National, the team scraped together $137,240 to make a pilot. That was about half of what it cost to make a half-hour animated program at the time, Lancit told Current, noting that about a third of that funding was quickly earmarked for the program’s testing and analysis.

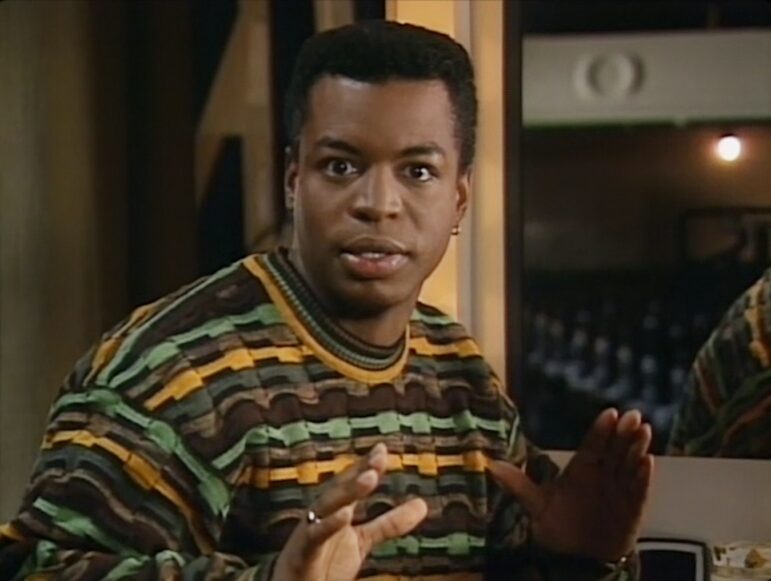

At Liggett’s insistence, the Lancits went in search of a male host for the series because more boys than girls typically struggle with reading. Burton was recruited to host because of his appearance in Alex Haley’s landmark Roots series, as well as his run hosting a couple of seasons of the kids series Rebop on WGBH. Burton had a personal connection to the material, too: In the documentary, he says that his mother taught English in the early part of her life before becoming a social worker, and that before training as an actor, he’d studied to become a priest, which gave him the belief that a life well lived should include service to others.

“With the Roots experience, I was able to observe this nation become changed, especially in terms of how we talked about chattel slavery,” Burton told Current. “Roots made it impossible to consider that slavery was simply an economic engine. You had to consider the human cost afterwards, and just eight nights of storytelling did that. So I was pretty excited about how we might be able to impact the lives of children who were at the point of making the decision about whether they would be a reader for life.”

And kids that watched Rainbow did become readers. In 1984, The Buffalo News reported that 6.5 million viewers saw at least one episode of the show a week, a number equivalent to what Mister Rogers and Electric Company were doing at the time. Buttino says that a study at the time showed that 55% of children’s librarians reported an increase in summer reading because of the show, with 73% responding that children asked for books featured on the show by name. Though the show had initially struggled to convince publishers to let them feature their books on the show, with most unable to picture how the material would actually be used, Rainbow had a massive impact on children’s book sales.

In Creating Reading Rainbow: The Untold Story of a Beloved Children’s Series, a book written in part by Buttino, the director of children’s book marketing for publishing house E.P. Hutton is quoted as saying that the series was the best thing that had ever happened to children’s books, because “books that would sell 5,000 copies on their own sell 25,000 copies” after appearing on the show. Publishers would instantly order paperback prints of books set to appear on the show, both to meet demand and to provide cheaper options to consumers. Truett Lancit says that parents felt that a book’s appearance on Rainbow meant it was worthwhile, and that libraries — where Rainbow books could often be found with a seal featuring the show’s logo on the cover — would often order multiple copies of each title just so they never had to turn away an excited reader.

The show’s success is evident in the documentary, not just through the archival clips and anecdotes throughout, but through the inclusion of former kids who appeared as guest book reviewers on the program, all of whom rave about their experience. Kenn Michael, a kid from the show who went on to become a successful actor-director-composer in Hollywood, calls Rainbow’s creators “bold and fearless” in Butterfly in the Sky. “Their love for what they were doing changed people’s lives,” Michael tells the camera. “You never know how far a simple effort of love can go.”

Butterfly also focuses on the show’s success in the education space, noting that for many years, Reading Rainbow was also the number-one television program used in schools across the country. “As the philosophy of American education moved toward integrated curriculum, teachers were able to use [the show] for their various classes in English, science, math and the arts,” Truett Lancit tells Current. “I don’t want to make it sound like the show was academically based, because it was not, but it filled a spot in American schools, so kids were getting it both at home and at school. We penetrated the audience over a long period of time in a very significant way.”

Behind the ‘Rainbow‘

Some of Butterfly in the Sky’s best bits come in its tales of the show’s creation, whether it’s producer Jill Gluckson’s story about how seriously James Earl Jones took his gig reading Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain on the show, or the time the camera spends with Horelick as he explains the origins and construction of Rainbow’s iconic theme song.

Viewers also get a look at how each episode of Rainbow was created, which always started with the discovery of a book producers liked. In “Animal Cafe,” for instance, producers enlisted Martin Short to read the titular book, which is about what animals get up to at night, while hanging at a 24-hour diner. In the episode’s field piece, the show’s crew filmed inside Bracken Cave in San Antonio, Texas, where something like 60 million bats cover every inch of cave’s walls and ceiling.

In the film, director Dean Perisot relays the difficulties of staffing the shoot — it is, notably, the only field piece Burton didn’t let himself get talked into — telling the story of a previously untested sound person who fell off a rock inside the cave during production, fell into the deep layer of bat guano and carnivorous worms that covers the floor of the cave, and ran out, ultimately refusing to return to the set. Coupled with descriptions of the harrowing Kilauea Volcano shoot for “Hill of Fire” delivered later in the doc, it makes the show’s production look brave and scrappy, committed to taking the kids watching at home right to where the action was happening.

That wasn’t the only commitment the show made to kids: Liggett says that early on, she laid down a rule that the show would try to represent all kinds of kids from all kinds of backgrounds, cultures and locations. It wasn’t something that producers necessarily thought to do in 1980, when the development process for the show began, but both she and Burton felt it was important.

And while viewers at home undoubtedly appreciated seeing Burton experience the sounds of African drumming and the taste of beautifully made Japanese food on the show, they also really enjoyed seeing Burton himself. In the film, Ellen Doherty — an associate producer on Reading Rainbow back then, now CCO for Fred Rogers Productions — says that Burton just has that special something that helps him connect with kids at home, relaying messages of sympathy, wonder and joy.

For viewers of color watching at home, Burton also felt like a revelation. Jason Reynolds, an author and poet who was the Library of Congress’ National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature from 2020–22, relates in the film over and over again how much seeing someone like Burton meant to him as a young Black kid. Burton, Reynolds remembers, wore a gold hoop earring, like two other important figures in his life, Michael Jordan and 60 Minutes correspondent Ed Bradley. Seeing that let him know that Burton was being his authentic self on camera, something that Burton says later in the documentary was always of the utmost importance to him.

It was important to Burton, too. He was always fiercely protective of his changing outward appearance on the show, defending his right to grow a mustache or experiment with a new hairstyle, despite what producers might want for continuity’s sake. As he explains in the documentary, “I’d been told my whole life by society that there was something intrinsically wrong or undeserving about me because of the color of my skin, and I think that made me especially recalcitrant to give in.”

It drove creator Cecily Truett Lancit especially crazy, leading to what Burton calls some “very tense and not inconsequential” conversations during Rainbow’s production. But as Lancit admits in the documentary, she knows now that she was in the wrong. “Levar knew better than I did that it would be OK,” she says. Burton told Current that he found that statement especially enlightening when watching the film.

There are other revelations in Butterfly in the Sky, such as teases that Burton almost left the show after the “My Little Island” episode in 1987 since he’d booked Star Trek: The Next Generation and was presumably off to greener and more lucrative pastures. The show even auditioned new hosts, though producers don’t give any hints as to who in the documentary. Ultimately, Burton reveals, he came back because he felt like there was work for him to do, kids to reach, and books to read.

“Every single day,” Burton says, “somebody comes up to me and says that, because of the show, they became a writer or a voracious reader or a beekeeper or even a visual effects artist because they watched the crossover episode where we went to the set of Star Trek: The Next Generation. I really think that the show delivered on its promise to expand a child’s knowledge of the world so that they might find their place in it.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified Bradford Thomason.