Why two young philanthropists are building a new media ecosystem

This essay first appeared on Transom and is republished here with permission.

Intro from Transom: Why would two young philanthropists (and PhD scientists) want to fund independent media? Fascinating question with fascinating answers. Elaine and Stuart Sevier are committing themselves to a new media model through their public charity, the Independent Media Initiative. They want to reconfigure established frameworks for media funding, distribution, and beyond. They want to help independent creators focus on what they do best: create great work that couldn’t be made by anyone else, work that defies the homogenization that can accompany corporate or commercial interests. The Seviers’ manifesto looks at the world of artful storytelling from the funding and supporter side. If you’re thinking about where the public spirit of our profession might go, check out “Building a New Media Ecosystem.”

Looking for a signal

We’ve spent the last five years using our perspective as scientists and funders not only to figure out why exceptional independent creators make the things they make, but to create an ecosystem that amplifies their signal.

How we got here

Five years ago we were living in Boston, pursuing ambitious careers in science. Elaine was getting her PhD in neuroscience at Harvard, and Stuart already had his PhD in physics and was working as a postdoctoral fellow at first MIT, then Harvard. Both of us were planning to become professors and do research for the rest of our lives.

But outside of research, we had a secret life. Elaine’s grandfather was a leader in the investment firm Capital Group, and he made a lot of money. With that money he started a foundation called the Shanahan Family Foundation, which today has about 400 million dollars. We got involved with the foundation because Elaine’s family wanted to do some funding around Alzheimer’s research, which her grandfather had. So during the day we were the low people on the totem pole slaving away in graduate school and postdoc life, but in the evenings and weekends we were suddenly decision-makers who could influence millions of dollars of spending. We were having meetings with people like the President of the National Academies of Science and executives at the Simons Foundation from inside a laboratory storage closet. No one knew.

It’s typical that foundations who support science research also support some kind of science communication. We were aware of this before getting involved with the foundation, having memorized the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation’s tagline from old Radiolab episodes. So doing something around science media was always on our minds. In 2021, we gave a grant to Radiolab to support their Mixtape series. It was a milestone for us as long-time Radiolab fans, but we wanted to do more.

Transom Manifestos from Soren Wheeler and Ira Glass have described how most science communication “smelled like school.” We agreed, and neither of us wanted to spend more time in school. We’d had enough! It also just didn’t feel real. It didn’t feel like the experience of doing research or gaining understanding. But science content on Radiolab and YouTube offered a world of engineers, researchers, and curious people who were making really fun and engaging audio and video that felt like discovery. They were and are also very popular — the most popular being Mark Rober, who has 44 million subscribers.

Stuart was especially a fan of two other popular channels: Smarter Every Day, created by civilian army missile engineer Destin Sandlin, and Stuff Made Here, created by mechanical engineer Shane Wighton. These people were making really great videos that were educational, and they were reaching millions of people. As active researchers, watching their work made us feel seen. The way they documented their struggles felt so real because it was real.

When properly wielded, YouTube and podcasts allow for pacing and authenticity like no other medium, allowing real people to share the simple, messy experience of life. It was in many ways the clearest signal that beautiful, modern, independently made educational content that didn’t come out of NPR or PBS could exist in a noisy world. So it seemed simple. We should support them.

A noisy world

Let’s talk about YouTube. YouTube doesn’t get a lot of attention on Transom, or in The New Yorker, or in your favorite arts and culture magazine. You might view YouTube as that annoying thing your kid is obsessed with, or where you learned how to fix your radiator. You might see all noise and no signal. We see that, too. It’s there. But if you look closer, you’ll find some of the most educational, creative and exceptional media being made today.

And like it or not, YouTube is the world’s largest forum for human expression. That means it includes the best of us and the worst of us. Its effect on the world and human culture is incalculable. The democratization of media creation has enabled millions of creators to share like never before and allowed billions of people to watch and listen. And its impact is only growing.

YouTube is where the biggest audience is, and it’s not going away. It’s a personalized global TV network that has totally upended media. It’s not just that people are watching videos about how to fix their radiators either: it’s the TV alternative. According to Nielsen’s January 2024 report, YouTube is the top streaming platform on televisions in the United States. Not YouTube TV — YouTube itself is more popular than Netflix, and more popular than Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, and HBO Max combined.

What does public media and public good look like in such a world?

This isn’t so unlike the situation Fred Rogers was in in the 1960s, facing down sensational programming on a newfangled and disruptive media platform: television. But it’s been almost 60 years since the Public Broadcasting Act was passed and we made a national commitment to public media. A lot has changed since then. Today, the best creators out there use the power and freedom of YouTube and RSS feeds to harness their independence and create things no one except them could create. They’re exceptional. In a space that incentivizes flash over substance, they’ve found a way to share authenticity in a manner and at a scale that has never before been possible. They’re the signal in the noise. So, how do we try to help those independent voices?

How to boost the signal

Getting into the philanthropy weeds for a minute: you can’t just give away money to whatever you want. For our purposes, there are two types of tax-exempt organizations in the United States.

The first kind is private foundations. Foundations have a lot of money, usually from a rich person or family, and they give that money away. The IRS requires that foundations give away 5% of their money every year. If your foundation has 100 million dollars, you have to give away 5 million dollars this year.

But it only counts towards the 5% if you give that money to the other kind of tax-exempt organization: a public charity. Public charities get money from private foundations, the government, and individual donors, and they use that money to do things like run homeless shelters, food banks, and media organizations. So in the case of Radiolab, the Shanahan Family Foundation is the private foundation and New York Public Radio is the public charity.

That means it’s very easy to give money to a public media organization or a university, but it’s not easy to give money to an independent person making media, no matter how much you think they’re doing a public service. You legally could do it, but it doesn’t count towards the 5%. So in practice, it doesn’t happen. Foundations only give money to public charities. Independent creators are just left on the table. So we couldn’t give someone like Destin a grant, even if he was making some of the best science programming ever made.

But we have public media for radio and television, right? In the case of video, why doesn’t PBS solve this problem? At first, it didn’t make sense to us why Destin wouldn’t just be supported by PBS, which has an online presence through the umbrella of PBS Digital Studios. The first inkling of doubt comes from the PBS Digital Studios tagline, which is “Your curiosity doesn’t stop when you turn off the TV.” OK, that’s not a great message. It took about a year for us to realize that not only was PBS failing to adapt to YouTube, but that it was incapable of doing so.

The sad part is that even if PBS wanted to, its charter is not set up to support programming in the digital space. PBS is much more decentralized than NPR; the national PBS organization is primarily designed to distribute programming that is made by member stations, not to produce programming. It also derives most of its funding from the member stations, who are funded by an aging donor population. In 2021, 46% of PBS viewers were over 65, 78% were over 50. Member stations that rely on their local donors are not incentivized to invest in digital programming, and the national PBS doesn’t have the funds or authority to reinvent its mission.

Truthfully, PBS is not attractive to most creators because of disputes over intellectual property rights, control of video output scheduling, and rights to seek independent funding sources and make decisions about content. This does not reflect a successful pivot by PBS into the digital space.

After about a year of talking to creators and institutions like PBS, we started thinking that if we wanted to support independent creators, we’d have to invent something new and that no one else would do it for us. The more we talked to creators, the more intense that feeling became.

Taking the leap

The problem was, we had careers! If you leave academia, you cannot go back. The job market is so competitive that you’ll never get hired once you leave. By the summer of 2021, Elaine was pretty sure she wanted to leave academia, but Stuart had spent 12 years training and preparing for a career in research. Stuart published nine research papers from 2011–22 and was building a new frontier in our understanding of how DNA regulates itself inside our cells. There are no guarantees, but people in his position don’t just walk away. We both viewed research as a calling and an act of service, the highest contribution a person could make.

But in the end, one weekend in California sealed the deal for us. We’d gone to the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics in Santa Barbara. It is physics heaven. A place where you can have Big Ideas about Important Things that take their time, while sitting on a beach. We were there to talk about funding a new program there, and we met with senior leadership. For Stuart, this should have been as exciting as it gets in terms of potential impact.

The discussion was interesting but felt a little flat. Where was the appetite for trying something new? For taking a risk? The pull to the status quo felt insurmountable. This is not specific to KITP; in fact, KITP is better than most. The promise of academia is that you’re not beholden to commercial pressures, so you can pursue the most important questions and deepest truths in a protected and free environment. In return for this incredible freedom, you make a lot of sacrifices. Income, stability, free time, choosing where you get to live.

But it felt more and more like the promise was failing. It didn’t feel like academic leaders were being thoughtful or trying to do something exceptional, and it became more and more clear how difficult it is to steer ships into uncharted waters. As Jay Allison said to us, over time all organizations become dedicated to money.

On our way to the airport we stopped off at YouTube creator Van Neistat’s house. His wife Isabel greeted us with a friendly, “And you are…?” We sat outside in their yard for two hours talking about Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and filmmaking and how to make a path for a true artist on YouTube. We left feeling totally electrified. It felt like there was a whole world out there where we could make a difference, where our contribution could be exceptional. Sitting on the plane back to Boston, we knew there was no going back. Stuart was going to quit. We were going to do this.

What am I going to tell my mom?

The independence of online media like YouTube makes it noisy and often comes with a patina that feels amateurish. However, the independence lends itself to authenticity. Drop your pretensions and take it seriously. The question is, how can we find the good? Who was making exceptional content and why? How could we help them make more? How could we help audiences find them? And even more than that, how can we change the creator ecosystem to make the creation of authentic, meaningful and exceptional content easier and more sustainable?

Soon after quitting, Robert Krulwich asked Stuart how his parents felt about him quitting his job as a Harvard physicist to go do some YouTube thing and help independent video and audio creators. Being a scientist makes sense to people. It’s aspirational. When Stuart left Texas to do physics research at MIT, his friend told him he was “doing God’s work.”

Truthfully, the reaction to quitting has been mixed. When you say YouTube, people automatically think “influencer.” When you say podcasting, they may think “murder show.” And compared to telling people you’re a Harvard neuroscientist or physicist, that’s a little embarrassing. Here’s the thing, though: people may outwardly respect academics and disdain influencers. But really, most people hate academics and love the characters they see and hear online. We are confident we found a place where the signal is real. Now we just have to figure out how to amplify it.

Sympathy for independent media

We started with trying to understand what motivates and influences the creators we love. We brought with us lots of sympathy. By sympathy, we don’t mean pity — we wanted to take our scientific, analytical perspective on the world and pair it with feeling. With Sympathy.

We started first by talking to YouTubers, but we were immediately led back to podcasters. Destin Sandlin connected us to Robert Krulwich, who then connected us to Jay Allison. It’s a big, small world. How can people from different walks end up being so connected in spirit? The short answer: they’re exceptional.

The first Smarter Every Day video ever made starts like this: “Hey it’s me Destin. So, um … we don’t have really awesome accents, and we don’t have a lot of money, but we do know our guns. And we are rocket scientists. So we’re gonna make a new web series called Smarter Every Day.”

He’s holding a Saiga 12, which is a 12-gage shotgun that looks like an AR-15, and explaining the difference between detonation and deflagration. A year ago he made a video about the physics of tractor pulls that got 2.5 million views. That was one of seven videos in a series about farming.

If you read that and your first thought was “redneck,” you’re not alone. That’s how a famous Ivy League mathematician and podcast host described him to us. But the thing is, he was clearly envious of Destin’s storytelling ability. Stuart’s MIT and Harvard physics colleagues don’t listen to Science Friday and they certainly don’t watch Nova. They watch Destin. And if you don’t, the person you sit next to on a train or plane does.

Destin is an unabashedly curious guy who lives in northern Alabama. He makes videos about things and people who are interesting to him. One of his videos is called “Two Vortex Rings Colliding in SLOW MOTION,” where he recreates a laminar flow experiment first described in Nature in 1998. With others, he spent over four years getting this to work so he could use high-speed cameras to track these vortex rings in slow motion and understand how they form. That video shows a true research process about something beautiful and totally obscure. It has 15.7 million views.

Recently we were at a dinner for Texas science funders at a table with a billionaire who was funding interactive science museum exhibits, with the theory that kids decide to pursue science because life is made of “five-second moments” that inspire you. We disagreed and said we got into science because people like Richard Feynman and Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich infected us with curiosity. So we brought up Destin, and the woman next to us just about jumped out of her chair. She said her daughter loved him, and they’d watched the video on laminar flow together. The last time her husband changed the oil in their car, her daughter wanted to help because of Destin’s video. She explained, pointed and said ‘Laminar flow, laminar flow’ as the oil gushed out of the engine. We didn’t talk about museums anymore after that.

Destin makes the most redneck things we watch, and also the most thoughtful things we watch. He is an exceptional creator who makes things that only he could make — and people love it. He can get 15 million people to watch a video about the strain energy equation, and make a girl excited about the physics of an oil change.

This is what independent media allows. Destin is exceptional. He is local, personal, authentic. He is using a platform to better his community through understanding. No one except him could make those videos.

So, who are other exceptional creators? When we think of Destin’s work, the person he reminds us of the most is Erica Heilman. Erica is the producer and host of the podcast Rumble Strip, where she interviews people in her community in Vermont. What does an Alabama science channel have to do with interviewing your neighbors in Vermont? They might appear different on the surface but have deep roots in common. Both Destin and Erica develop arcs over years: Destin has made seven videos about a phenomenon known as the Prince Rupert’s drop and a local glassblower named Cal over the course of 10 years. Erica has featured her friend and private investigator Susan Randall on the podcast seven times over nine years and spent seven years interviewing her neighbor Leland while he grew up.

That long-term engagement emerges when you’re really invested in people. Destin and Erica are both hype-local in their storytelling. Occasionally Destin will fly somewhere for a story, but most of his videos are set within the state of Alabama and have a strong sense of place. They feature local people whom Destin cares about. Local farms, local manufacturing plants, the U.S. Coast Guard on the Gulf.

Erica is a genius of local storytelling. Everything she makes is grounded in her community and a deep sense of care for the people around her. Because of that, she can make shows about culturally sensitive topics like guns and social class. Both the people she interviews and her audience trust her to take them to a place that usually makes them uncomfortable.

Erica and Destin do the kind of work that builds social cohesion: making people all over the world fall in love with farmers and veterans and their neighbors. The kind of work public media is supposed to do.

Celebrating Exceptional Creators

Two years ago we created a new public charity, the Independent Media Initiative. Independent media needed a legal and financial mechanism to directly connect public support to public good in the independent ecosystem, and if no one else would do it, we would. IMI is that mechanism.

More than anything, we wanted to let others see what we were seeing in creators like Destin and Erica and build new support models around them. In 2022 Erica won a Peabody award for the episode “Finn and the Bell” about a teenage boy named Finn, who committed suicide in 2020, and how the community dealt with that tragedy. Rob Rosenthal interviewed Erica for Sound School about making that show. In the interview she says:

“If you make something alone and not made by committee, it has a particular peculiarity to it that is beautiful.”

We believe that independent media creates a peculiarity that is beautiful. That it should be taken seriously and consumed with feeling. That we should look for the exceptional in the mundane and see the global in the local. We believe that the people making this work deserve public support because they make the internet and our society a better place to be. We believe that if we can build systems that help highlight and amplify the works of these creators, audience support will come rushing in. That is the manifesto of IMI.

To start, we’ve created a new set of awards. The awards have a real financial component so they empower creators to keep making what they make or try something new. Money also brings a sense of prestige, which helps amplify the intrinsic value of the work independent creators make.

We gave out the first awards at the inaugural IMI Fest in November of 2023, which had a day of creator-only workshops and a day in celebration of independent media. We built interactive exhibits and had video and audio screenings, including the debut of Audio Flux in partnership with Julie Shapiro and John DeLore. You can view the speeches made by our award winners on our YouTube page and let them tell you what the award meant to them. We’re also experimenting with a residency program and other ways of incubating and supporting independent creators.

Beyond the awards, our evolving strategy is to help catalyze a new public media ecosystem. We’re inspired by the Sundance Film Festival and the impact that it had on independent film in the 1990s. We hope that by bringing the right people together and pulling in new support from foundations and individual donors, we can help audiences find the signal in the noise.

Money is not enough: What drives a media ecosystem?

Of course, as scientists we have to end with a science analogy. You might hear the word ecosystem and think “fragility,” or “predator” and “prey.” But what really connects organisms in an ecosystem is energy flow: most ecosystems on Earth are driven by the sun.

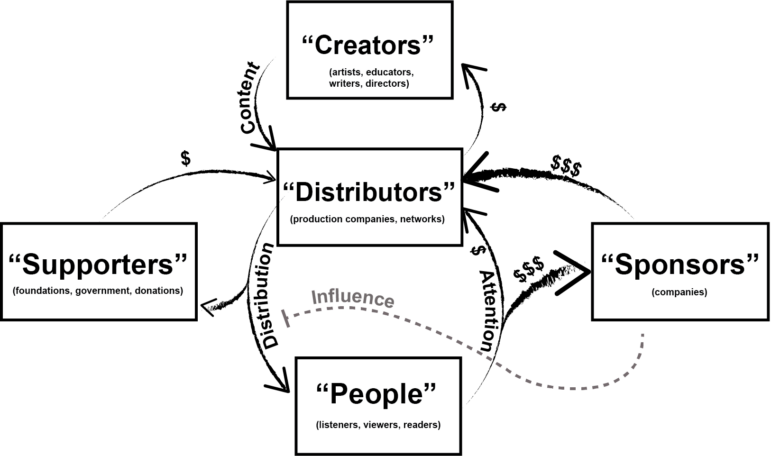

What drives a media ecosystem? In a media ecosystem, you have media producers (creators) and media consumers (audiences). You also have production companies and networks (distributors) and money (advertisers and supporters). It’s natural to assume that money drives the system.

But really money, and everything else, is driven by something else: attention. On PJ Vogt’s podcast Search Engine, guest Ezra Klein makes the case for individual attention-generating media. He says, “We are generators of the internet, we are generators of the media. What we give our time, attention, and money to thrives, and what doesn’t get it is what dies.”We take this very seriously at IMI. When Destin made a video acknowledging support from IMI in the form of an award, we asked him to ask his audience to be thoughtful about the next thing they watch. In the past, distributors and organizations like PBS and NPR had a lot of control over what got attention. PBS, NPR, and the indie film world are media ecosystems that support beautiful work; they showed the world that it was possible for beauty to exist in that medium. They captured the attention of a powerful audience that demanded high-quality and respectful content, and gave money to support it. That ecosystem looked something like this:

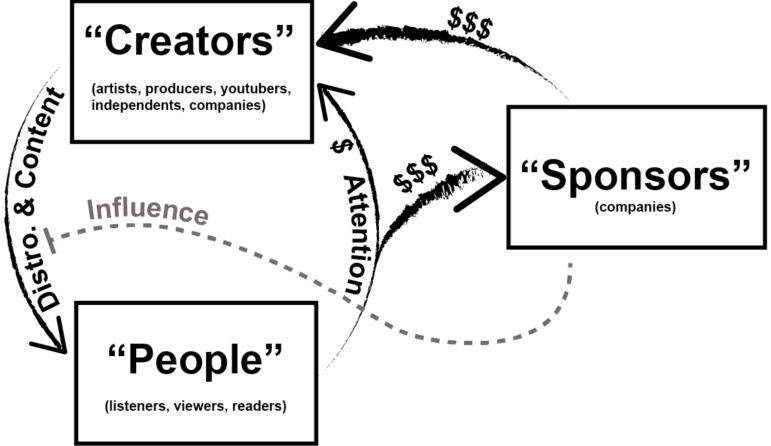

But today, the internet has removed the distributors from the equation. Self-distribution is now the norm. Because there’s no public support of independent creators, the “supporters” are gone as well. We’re left with sponsors who fund creators directly and want to capture as much attention as possible, which leaves creators vulnerable to strong influence from advertisers, or left out in the cold. Today the ecosystem looks like this:

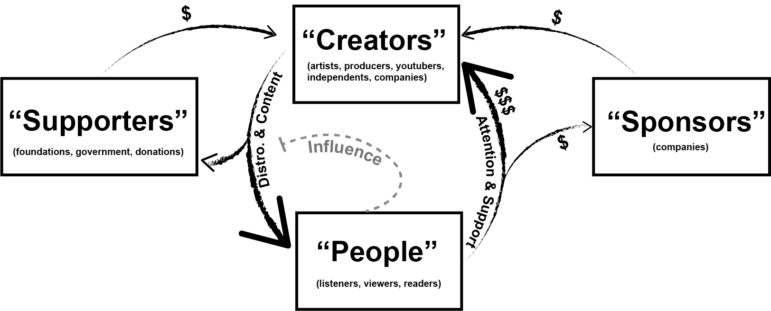

So what do we mean by “Building A New Media Ecosystem”? Essentially, we mean three things. First, we’re trying to convince everyone that a new ecosystem supporting independent media is necessary. Second, we’re building the pipes that allow philanthropic and noncommercial support to come in, balancing the influence that sponsors get to have over what gets made. Third, we want to bring attention to exceptional independent creators to help them build sustainable audiences. This is the ecosystem we want to build:

Our primary goal is to strengthen the loop between creators and people. To catalyze the energy flow between those “organisms” in the ecosystem. We want audiences to reclaim their agency and consume media that provides value to them, rather than letting advertisers and algorithms hold the power. That takes commitment from creators to make exceptional work and commitment from the audience to demand it and consume it with feeling.

Ultimately we hope this can be self-sustaining and exist on a scale that we could never support directly. Sponsors and even philanthropy should have as little influence as possible over what’s getting made in a public ecosystem. NPR, PBS, and Sundance all did this effectively for their corner of the media world, but it hasn’t happened yet for the internet.

There are many reasons why this might not work. For one, we don’t have enough money to help everyone who deserves it. It is so, so easy for a foundation or individual to give money to PBS or NPR or Harvard. We have to make the case to the billionaires and the makers and the audiences like you that YouTube and podcasts are the present and future of media and that we have a chance to build a new public media ecosystem that supports the weird and wonderful. We want to be the catalyst that creates a funding structure and a permission structure for that.

The scariest part is, it’s possible that the thing that makes independent media so great is the thing that will kill it, that the independence will be too much to wrangle into something coherent enough that other people understand it. Independent creators are naturally anti-institutional, and funders are wary of wading into unregulated waters. The gatekeepers are gone. Who knows what will come next?

There is so much work to do. Building a whole public media ecosystem doesn’t happen overnight. We’ve only just started. For now, though, we ask just this: be thoughtful about what you watch or listen to next. The more you think of your attention as the light that drives our shared media ecosystem, the more we can collectively focus it on the areas full of beauty and wonder.

Editor’s Note: In 2022, IMI supported the initial planning phase of The Transom Story Lab at Atlantic Public Media.

Elaine Sevier is a co-founder and Director of Strategy of IMI, the Independent Media Initiative. She is also the President of Research Theory, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to fostering creativity and innovation in science. Elaine has a Ph.D. in neuroscience from Harvard Medical School.

Stuart Sevier is a co-founder and President of IMI, the Independent Media Initiative. He is also Director of Strategy for Research Theory, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to fostering creativity and innovation in science. Prior to founding IMI and Research Theory, Stuart obtained his Ph.D. in physics from Rice University and was a postdoctoral fellow at MIT and Harvard Medical School.