How a new tool is helping stations boost election coverage

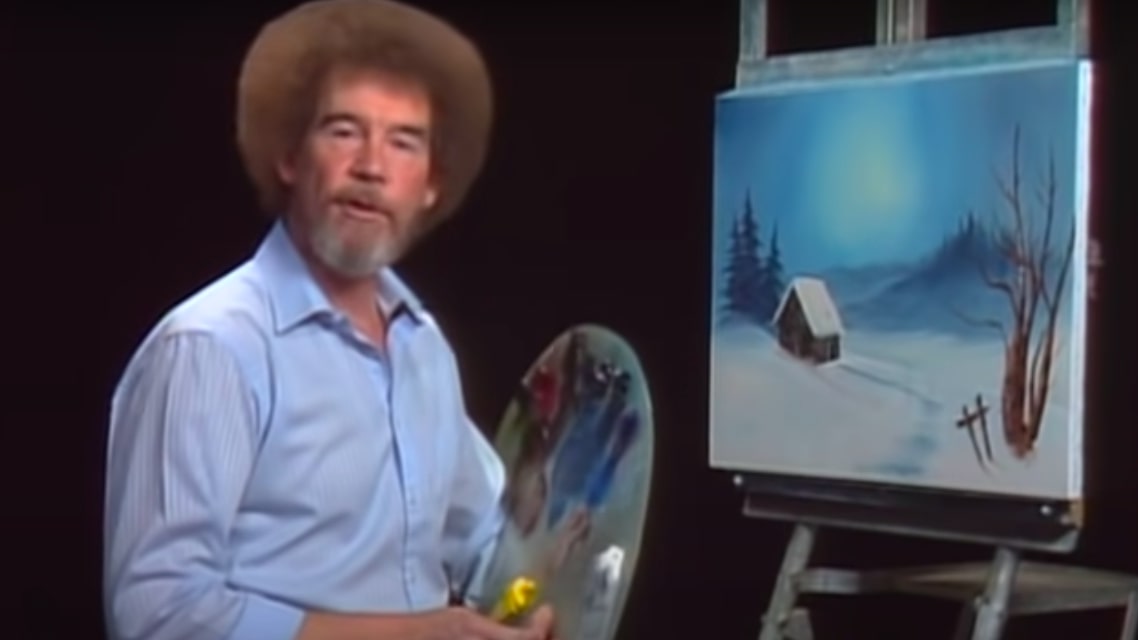

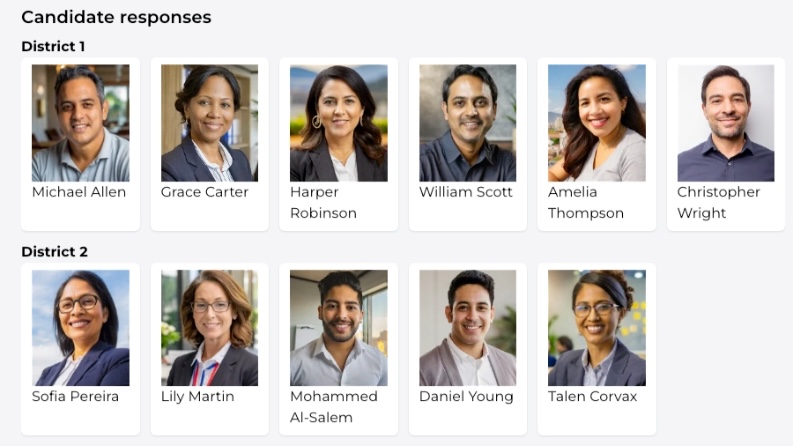

A demo of the ElectUp backend.

From mayors and city councils to district attorneys and the president, Americans have much to vote for in 2024. Public media has a crucial role to play, both in reporting electoral races and helping audiences navigate potentially overwhelming amounts of information about candidates and their standpoints.

Public media consistently offers “access to third-party and minority candidates often ignored by mainstream outlets, giving a voice to disenfranchised voters and marginalized populations, and examining the electoral system and the media’s influence,” says the American Archive of Public Broadcasting.

A platform initially developed at Alaskan broadcaster KTOO wants to help public media do just that. Designed with coverage of local and state races in mind, the election guide creation tool ElectUp allows newsrooms to put questions to candidates and display their responses in a customizable format, and enables audiences to easily compare responses.

Its creator, journalist-turned-developer David Purdy, spoke with Current about how he built the tool, what it brings to newsrooms and audiences, and plans for the future.

How ElectUp was built

Purdy, who has a computer science background, joined KTOO in 2015 as a producer. He first developed ElectUp as an internal tool to help the station organize its election guides, which were manually created by the newsroom’s digital editor. This process could take weeks as the editor collected responses from candidates, made profile pages and built comparisons among candidates’ answers on each surveyed topic.

“It was not a good use of a talented editor’s time,” says Purdy, who had previously done some development work on KTOO’s website. “I like getting computers to do things that computers are good at that journalists don’t need to do. Journalists have plenty of demands on their time, and if it’s something like copy-pasting or collating data, it’s great to free up an editor’s time to do things that actually need their skills.”

With ElectUp, editors decide what questions to ask candidates and what topics to focus on, from why they are running to how they work cross-party. They can then review responses before publishing. On the public-facing side, it creates a simple way for audiences to search, read and compare the answers.

The first iterations of the tool were built as a WordPress plugin for KTOO’s site and required journalists to collect candidates’ answers separately and enter them into the ElectUp backend. Former VP for News and Managing Editor Jennifer Pemberton joined KTOO in 2016 when ElectUp “wasn’t much more than a spreadsheet”.

“Each election cycle brought an opportunity to work on the tool and make it better,” she says. KTOO’s editorial team developed the editorial side of the tool, while Purdy worked on how the content would be best presented to audiences.

“A good candidate guide needs a newsroom that’s in constant conversation with its audience — actually, not just its audience, but the whole community — because elections touch everyone in town, not just a given outlet’s listeners or readers,” says Pemberton. “People need a lot of information sometimes about a lot of candidates to be sufficiently informed to vote. ElectUp gives newsrooms an efficient way to organize and present that information to voters that feels very intuitive.”

From internal tool to external platform

Building a first working version and getting it out as quickly as possible is crucial when developing new tools in small newsrooms where resources are tight. “There’s always ways you can improve it, and internal users will be the most forgiving,” says Purdy. “This process [at KTOO] allowed me to try the whole tool to begin with and to try new ways every year without needing to have something fully fledged.”

In 2022, after Purdy had left KTOO and Alaska, other media in the state, including the Anchorage Daily News and Alaska Beacon, asked to use the tool. KTOO agreed to share the code, and Purdy built a version that could be used by non-WordPress newsrooms.

Taking ElectUp from an internal-only tool to something used by multiple newsrooms with different needs and digital setups was a challenge. “I realized the solution I built was working but wouldn’t scale very well to a lot of organizations using it, especially higher-traffic organizations and bigger markets,” says Purdy.

To make it more usable, he rebuilt the tool outside of WordPress as a standalone platform using the web application framework Laravel. This allowed more features to be added and greater customization by different newsrooms.

The latest addition allows newsrooms to survey candidates and collect their responses through the ElectUp platform rather than having to use a separate questionnaire tool, such as Google Forms. This eliminates much of the manual data entry, as candidates can enter answers directly into the tool. “All that’s left is for an editor to edit and publish,” says Purdy.

Collaborative election guides

ElectUp is also built for collaboration: Newsrooms can work together on election guides and publish them jointly or select individual races to share that are relevant to their audience. Pooling resources and credibility can help elicit responses from candidates, too, says Purdy.

Collaboration between newsrooms can often be challenging owing to different content management systems or unfamiliarity with another newsroom’s operations. Having ElectUp as a separate platform that can be embedded and customized to suit individual newsrooms helps overcome this hurdle, he adds.

In 2022, Alaska’s four biggest newsrooms collaborated on one shared candidate guide using KTOO’s tool for the state’s first-ever ranked-choice election. It was “the greatest testament to the tool’s success,” recalls Pemberton.

Developing a tool like ElectUp had an impact on how KTOO covered elections, she adds: “We had to resist the urge to do horse-race coverage and dig deeper to make sure our coverage was focused on issues, not on candidates. That can be really hard in small communities. There would be no ElectUp if we didn’t have a newsroom committed to doing election coverage differently.”

Mary Shedden, news director at WUSF in Tampa, Fla., agrees with this shift in election coverage. Over the past 11 months, she has led the charge to get 12 public radio stations in the state to collaborate on election guides using ElectUp.

With a staff of 20, producing high-quality election guides for the 13 different counties that WUSF serves wasn’t previously possible. But working with other newsrooms in Florida enables the station to go beyond its means and provide “the ultimate public service,” says Shedden.

“We’re the third-largest state in the country, and we don’t pay a lot of attention to the statewide races,” she says. The 12 stations will use ElectUp to gather and share information on Florida’s forthcoming state house and senate elections, as well as congressional elections and the U.S. presidential race — more than 200 election races in total.

The newsrooms can also use ElectUp for local elections, but having an agreement in place for collaborative state elections coverage means that even the smallest-sized partner with little to no newsroom will be able to run candidate guides. The newsrooms have created an editorial board to set guidelines, including what questions to ask and how to deal with unresponsive candidates.

“I hope the public will have a non-editorialized, non–opinion-based, non–candidate-driven resource and be able to make a side-by-side comparison of the issues that they care about,” says Shedden. “I’m a long-time Floridian, and I know we need it.”

Helping audiences in the future

Purdy is exploring how audiences could interact with the guides and retrieve candidate information in a format suitable to SMS services and how to make the guides print-friendly for audiences who don’t access election news and public media via websites.

“The big-picture objective is to make the information in election guides available and accessible to as many people as possible regardless of their situation, including ability, technology and connectivity,” says Purdy.

He’s also working on ways to localize election guides that would allow a user to enter their address and see candidate and election information relevant to their location. The challenge with localization is largely technical, involving expensive data and data-sharing processes, says Purdy: “I’m trying to keep the cost of the platform down for local newsrooms, but it’s so critical that it be completely accurate.”

Prices for ElectUp start at $1,200 for a year’s access for small newsrooms. Purdy says he wants to keep the pricing simple and will offer different pricing tiers based on organizational revenue but not on audience size or number of newsroom users. Newsrooms working collaboratively can discuss a package tailored to their needs.

While Purdy wants to add features to increase ease of use and efficiency for newsroom users of the tool, what ElectUp offers audiences is, arguably, of even greater importance.

“Most users view this guide right before they fill out their ballot paper,” says Purdy. “It is not necessarily about producing more information but about narrowing it down and distilling it to what they need to make a decision.”

“The tool helps local elections be less of a popularity contest and creates informed voters who will get exactly what they expected from their candidates once they are elected into office,” adds Pemberton.

Having someone in the newsroom like Purdy dedicated to work such as UX should be more of a priority, she says: ”Journalists need someone who can take all your audience insights and engagement work and translate it for the screens where people interface with your newsroom the most.

“It may be hard in a small newsroom to give up a reporter position, but the amplification you’ll get from having someone doing this kind of work will be worth more than one full-time equivalent.”