From ‘nice’ to ‘necessary’: How to make a case for your university station

Chris Evans

University of Illinois journalism students Charrice Jones, left, and Vivian La report for the Illinois Public Media Student Newsroom.

What are the questions that keep you up at night? Current is here to help!

In this column, public media veteran Scott Finn taps into the wisdom of the system to find answers. This time, he helps university licensees make the case to university officials. Future columns will look at state and community licensees.

A new university president. An enrollment decline. A budget cut from the legislature.

Any of these changes can disrupt the relationship between a college or university and its public media station. Penn State’s proposed 20% funding cut to WPSU is just the latest example. How can university licensees compete for scarce resources?

Here’s how one Penn State official explained the decision: “They’re trying to invest where they believe they’re going to get the most value for that investment in students.”

Translation: Penn State leadership is directing money to departments they believe lead to student success.

You may disagree with the university’s priorities, or think their perceptions about the station’s value are unfair and inaccurate. That’s not the point. To convince university leaders of your worth, you need to understand what’s important to them.

Their ‘D’, not yours

There’s a formula for change you can apply to any situation, work or otherwise:

CH = D x V x P

Change = Dissatisfaction x Vision x Process

Change is your desired goal — in this case, to improve the perception of your value to university officials.

Dissatisfaction is the reason someone is not happy with the status quo. Vision is a picture of what success looks like. Process is how we get there.

Here’s one real-life example. You want to wake up one hour earlier — that’s the change. Your dissatisfaction comes from the chaotic rush of getting everyone off to school and work on time. Your vision is watching the sun rise while drinking coffee, then calmly getting ready. The process is moving your alarm and bedtime back two minutes each day for one month, until you’re waking up an hour earlier.

Here is the most important thing to remember: The dissatisfaction has to belong to the person you want to change.

In the case of influencing the university, what’s important is their “D” — not yours.

Understanding your university audience

It helps to put university leaders into a public media framework as an audience to be understood and a donor to be cultivated.

Peter Dominowski brings his experience in audience development into his new role as executive director of the University Station Alliance, the affinity group for university-owned stations.

To reach your audience of university officials, Dominowski says to start with research. What are the priorities of university leaders? To increase enrollment? To boost scientific research? To balance the budget?

If you’re dealing with someone new, why were they hired? What is their previous track record? What do they know and believe about public media?

“You can’t assume they know what you’re doing. Show them and tell them,” Dominowski said.

Higher education leaders in the U.S. are dealing with declining numbers of high school graduates. They’re facing unprecedented competition and financial pressures.

What are you doing as a station to help them solve their problems?

Sometimes, university leaders need to be reminded of how public media’s huge reach builds name recognition and positive brand association for the university. U:SA has a formula to help its members show universities the monetary value of all that publicity, as well as its membership, underwriting and community service.

Also, university officials may be aware only of a station’s broadcast service. Make sure they know about podcasts, YouTube channels and Instagram feeds.

This brand equity and goodwill helps recruit new students to campus. Dominowski compares the reach of a public media station to attendance at a football game.

“There might be 60,000 people in a football stadium, but public media’s reach is far greater,” he said.

Teaching hospital

Increasingly, goodwill and brand-building are not enough. Universities want to see the direct impact of their investments on their students.

Students are a huge, largely untapped resource for public media stations of all types — especially those on college campuses. I believe this so strongly that I’m working with the Center for Community News to grow partnerships between college reporting programs and local public media organizations.

A recent CCN study shows that only about half of university licensees air student stories, and only 11% partner with a college class. But 91% of public radio stations want to collaborate more closely with their college or university.

For a long time, public media organizations were reluctant to use student work because of quality concerns, Dominowski said. Today, stations have more platforms to publish student work. Meanwhile, support from faculty can help student-created stories meet the high standards of public media.

Increasingly, public media stations are positioning themselves as “teaching hospitals” for journalism. Just like a teaching hospital, they can provide top-quality service to the community while educating students.

One of my current clients, WSHU, is growing its student journalism program at universities on both sides of Long Island Sound: Sacred Heart and Stony Brook. It’s not just big journalism schools like the University of Missouri and KBIA, but smaller programs like the University of Nevada-Reno and KUNR.

The benefits aren’t just for future journalists. My former employer, Vermont Public, has developed a robust student reporting program with the University of Vermont — even though the station is not licensed to the university, and UVM doesn’t have a journalism major!

Students who report on their local community develop skills that are valuable in ANY job — research, writing and presentation.

Finally, journalism isn’t the only way you can partner with your university. Many stations sponsor internships in engineering, development and marketing. Education students can help stations develop curricula. Students can create music, interactive games, animation — the potential is endless.

Moving from vision to process

So, how would you apply the Change = Dissatisfaction x Vision x Process equation to your university?

Let’s say you want to create a stronger, more reliable relationship between your station and the university. How you define stronger is up to you — for some, it’s money; for others, in-kind university resources. Or maybe it’s more freedom from university rules.

CH = a stronger relationship with your university

Remember, the “D” is the college administrators’ dissatisfaction, not yours. Let’s say they want to become a more well-respected research engine.

D = University’s desire to become better known and respected for research

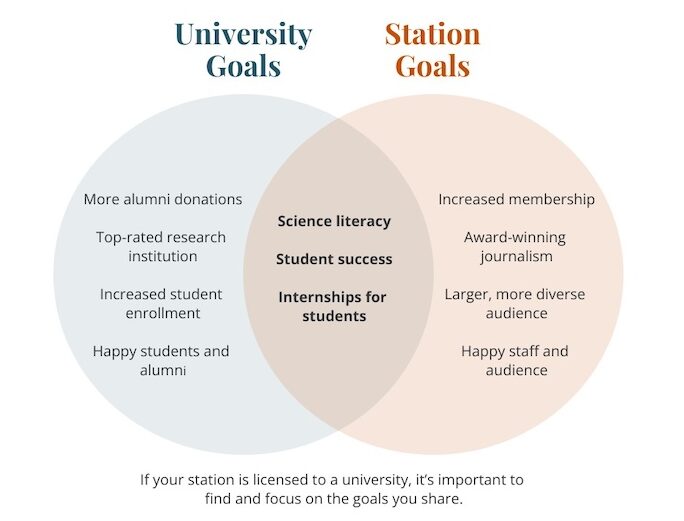

What’s the potential vision? I suggest you create a Venn diagram with two circles — what my public media organization does, and what the university wants. Where do those two circles overlap? (If there’s NOT much overlap, you have a problem.)

In this case, the vision is knowledge of and appreciation for scientific research among students and the public.

V = A student body and broader community that understands scientific research

Finally, the process is how we move toward our vision. In this case, the university and station could seek a grant to expand science literacy on campus and in the larger community.

P = Grant-funded science literacy media project

From ‘nice’ to ‘necessary’

Here’s the thing: colleges and universities don’t have to sponsor public media organizations. Your mission and their mission need to align or, eventually, you’ll be in trouble.

If worst comes to worst, you can remind university officials of the negative consequences of a budget cut or of selling the station. You could talk about the pain they’d experience from angry, tote-bag–carrying fans, and imply the damage will be greater than the savings or the value of selling out to, say, a Christian broadcaster. But these talking points are a last resort.

I used to run a state licensee (more on that in a future column), and we received one-third of our funding from the state legislature.

A mentor once told me, “To them, you’re nice, but you’re not necessary.” Those words haunted me, and I spent my tenure doing everything I could to go from nice to necessary in their minds.

If you’re more nice than necessary to your university, be ready to change that equation.

Scott Finn owns Finn Advising, which helps the people who are rebuilding local news. He’s worked as a GM at West Virginia Public Broadcasting and Vermont Public, a news director, an award-winning reporter, and a really bad whitewater rafting guide. Have a question you want tackled in a future column? Email Scott at finnadvising@gmail.com.

I’ll say at the outset, this is a great article, Scott. And it’s raising issues that far, far too many people at university licensees are in deep denial about. I know one particular institution at a state university whose leadership often brags about how “fiscally independent” they are…conveniently ignoring that a whopping FORTY PERCENT of their annual budget comes from direct cash support and in-kind contributions (e.g. free rent, free internet, free HR, etc) from the parent university.

Unfortunately, I think public radio’s ability to go from “nice” to “necessary” is far more limited than any of us want to realize.

The hard truth is that many, many colleges face existential crises right now. I’m not even talking about political attacks in red states; that’s bad enough, but we can put it entirely aside for this discussion. I mean there was a huge baby bust about twenty years ago and it’s now showing in plunging enrollment numbers at colleges across the country – both public and private. Couple that with the overall arms race of student services that’s happened over the last 30-odd years, and how inflation over the last three have wildly increased the costs of those services? And there’s quite a few colleges that won’t be in business by the end of the decade.

When that happens, none of the arguments you’ve made…as good as they are…will mean mouse farts to a parent college that’s facing its doors closing. There’s only two things that MIGHT matter, and one more than the other…

FIRST: IS YOUR RADIO STATION PART OF A FORMAL COURCE CURRICULUM? I don’t mean internships. I don’t mean student volunteers. I don’t mean electives. I mean: are their classes students cannot take without some manner of formal study happening within your radio station. Very, very few pubradio stations meet this criteria. I’m not even sure of it’s still true at WERS, and Emerson College is one of the top schools for communications in the country. I *know* it’s not true at WBUR, and Boston University has one of the top broadcast journalism programs in the country.

If you’re not part of a formal curriculum, then when dollars are really tight and the university must choose between funding your radio station and funding the chemistry department? The chemistry department is going to win every time. If you ARE part of a formal curriculum, at you have a fighting chance to get those dollars. Your odds still aren’t good, but you have a chance.

SECOND: IS YOUR BUDGET INDEPENDENT OF THE PARENT COLLEGE? This is really your only true protection against a college who’s cuttingcuttingcutting the budget. And you need to be truly *independent*. If you aren’t getting any direct cash funding? That’s a good start! But what about the in-kind stuff? Are you getting free rent for your tower/studios? Free internet/phones? Free janitorial/security? What about parking and snow removal? Do you get free help on payroll processing, accounting, or HR from those departments at the college? Do you have enough cash to pay for your employees’ healthcare benefits if the college kicks you off their plan? What about for retirement plan matching contributions? Does the college physical plant handle major maintenance and repairs for things like building HVAC or generators? Or even just regular “household” maintenance in the studio building?

If you answered “yes” to any of these? You’re big-time vulnerable. You need to start reorganizing your budget to pay for all this (or an equivalent schema) yourself. Because at any moment, you could be forced to start doing so.

Two more quick hits of proactive things your radio station can do: One, start up an independent “Friends of WXYZ” 501(c)3 that exists solely to manage an endowment fund. Do this in the knowledge of your parent college’s business and alumni offices, but don’t let them stop you, either. Besides having a nice reverse of cash to fall back on if you need it (and a source of ongoing revenue as well), you want a budget that the whole university knows is YOURS. That if someone gets frisky with your budget, you’ll have the reserves to fall back on while you fight back against the interloper.

Two, start going to faculty department chairs and make friends with them. Ask them to include funding requests for marketing when they make grant applications to the National Science Foundation. It will take a least one full budget cycle (e.g. 12 to 18 months) before this can even begin to bear fruit, but it could be supremely valuable once it does. The NSF has bemoaned for decades how the public doesn’t know about, understand, or care about all the things they fund. They are looking for excuses to give money to campus-based researchers to go on your airwaves and talk about why that million bucks in NSF funding to buy new, special, HVAC air handling systems is what allows for high-energy physics experiments to find the building blocks of the universe. Or whatever. The funding doesn’t buy airtime for the interview, of course…that’s illegal. But it can buy underwriting spots that “promote” the interview show incessantly. There’s ways to make it work, and the money is sitting there, just waiting to be asked for.