Friendships forged on TV cooking sets keep ‘Sara’s Weeknight Meals’ on the air

Courtesy Sara's Weeknight Meals

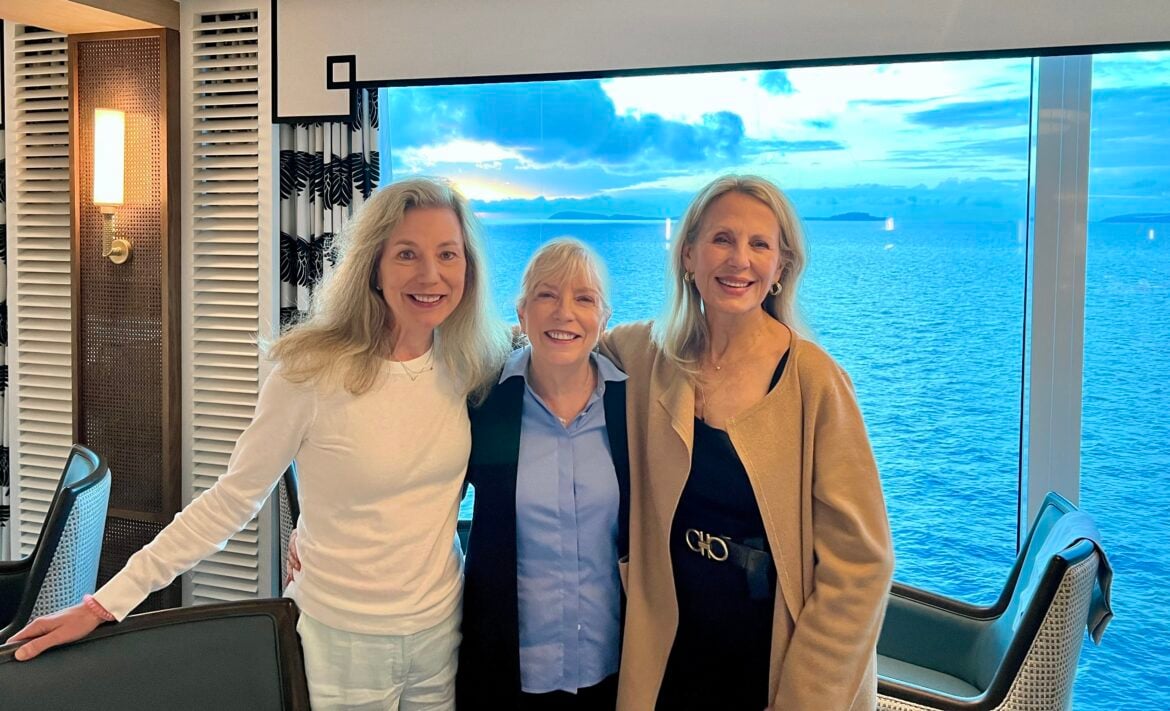

Stephanie Faison, Sara Moulton and Natalie Gustafson of “Sara's Weeknight Meals,” pictured on their recent cruise as the ocean liner moves from Gulf of Naples into the Tyrrhenian Sea.

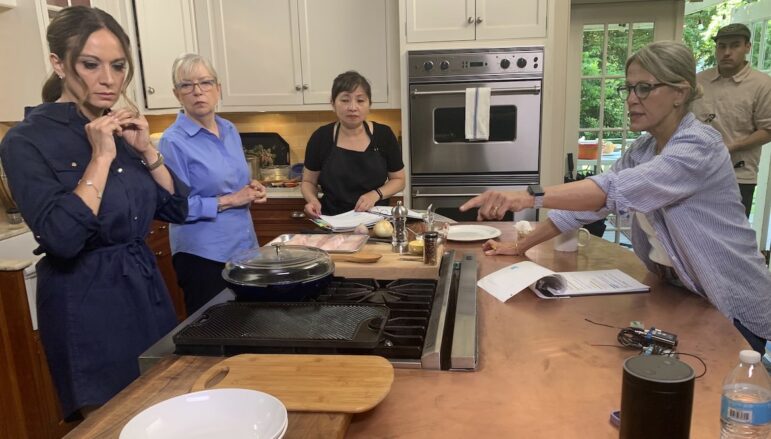

On a weekday morning in mid-June, a TV production crew took over Natalie Gustafson’s home in suburban Connecticut.

Gustafson is a veteran producer and director of cooking shows whose career includes eight years with the Food Network. The impressive kitchen in her home features a gas cooktop built into an island with an 8-foot-long heat-resistant copper countertop. A high-end stainless-steel refrigerator and double oven are built into the cabinetry, and an oval window over the kitchen sink looks out onto the lush greenery of the backyard.

Large butcher-block–sized cutting boards and containers holding a variety of recipe ingredients were laid out strategically on the countertop. In a kitchen that home chefs would die for, Gustafson confided that she lets her husband do all the cooking. “That’s my dirty little secret,” she said with a laugh.

And yet for three days in early summer, chef Sara Moulton was behind the cooktop while camera operators, a sound mixer, a culinary producer and assistants, a makeup artist and interns were all over the kitchen and adjoining rooms. There was plenty of food prep underway, but meals for the crew were catered to get them through 10-hour workdays.

Sara’s Weeknight Meals, the public TV cooking series that Gustafson originally created with Moulton for Gourmet magazine, was wrapping production on its 12th season. Gustafson and Moulton now co-own the series and distribute it for national broadcast through American Public Television. The package of 10 new episodes, which Gustafson’s Silver Plume Productions will deliver for broadcast in October, feature highlights from foodie adventures filmed during a recent cruise around southern Italy, along with the culinary magic that Moulton worked up this month in Gustafson’s kitchen.

Gustafson directed the shoot from a tiny mudroom after Moulton and two guest chefs walked through the preparation of pesce all’acqua pazza (an Italian dish of white fish sauteed with cherry tomatoes) and turkey keema (a curry made with ground turkey, tomatoes and peas). Moulton, who stands about five feet tall, and her guests move around a 3-inch platform that the crew set up behind the island, out of view of the cameras.

Diminutive in stature, Moulton’s lifetime of culinary knowledge and skill in cooking with ease on TV sets have made her a giant in the world of food television, according to colleagues and peers.

“The first time I saw Sara on camera, I recognized she has a unique ability to have a conversation with the camera,” said John Potthast, who produced multiple cooking series for public TV, including shows hosted by Pierre Franey, Julia Child and Martha Stewart.

“When viewers are watching Sara, there is a very strong feeling that she’s sitting on the stool in your kitchen and having a cup of coffee with you,” said Potthast, who is credited as an EP on the show. “That’s a rare and extremely valuable talent.”

Gustafson first crossed paths with Moulton at ABC News, where Moulton prepped for chefs and cookbook authors who appeared on Good Morning America before becoming the show’s food editor and an on-air contributor. Later they worked together at the Food Network, where Moulton became one of the cable network’s first stars as host of Cooking Live.

A 2006 New Yorker piece on the rise of food television called Moulton “one of the few people knowledgeable enough to field live phone-in queries.” She did it while simultaneously cooking and interviewing guests. Moulton now answers audience questions for Milk Street Radio, the public radio show and podcast hosted by Christopher Kimball.

“There is no other female culinary personality with her kind of experience and her power to influence people simply because she is so incredibly knowledgeable and so charismatic,” said Stephanie Faison, development director for the show. Faison is one of the “Three Musketeers,” with Gustafson and Moulton, who keep Sara’s Weeknight Meals on the air. She played a pivotal role in resurrecting the series after the Great Recession.

A veteran publicist and marketing professional for the food industry, Faison knows Moulton from way back. “She’s not imposing in any way,” Faison said. “One of her greatest assets is that she is the least threatening, most approachable person on the planet.”

Esteemed French chef Jacques Pépin, star host of multiple cooking series produced by KQED in San Francisco, described Moulton’s recipes as “first-rate” in an email and added, “There are many cooking shows on TV, but few are teaching anything. … To learn about cooking, look at Sara Moulton.”

‘Let’s do a show together’

During hertime at the Food Network, Gustafson produced several shows and specials, two of which won Emmys for directing. One year she was in charge of a Thanksgiving special that featured all of the network’s show hosts.

“We were all supposed to pretend we were great friends when some of us had never even met before,” Moulton recalled. “It was ridiculous.” But she was struck by the exceptional job Gustafson did on the special, which the chef likened to “corralling cats.”

“Natalie doesn’t see it as her brightest moment in terms of producing, but I do because I knew what she was up against,” said Moulton. “Anyway, it planted a little seed in me that, ‘Oh, she’s good.’”

In working together, Gustafson and Moulton discovered they had a lot in common.

“We got married at the same time, we had kids at the same time, we worked at Good Morning America at the same time, and we were both working mothers with a problem,” Gustafson noted. “We were working all day and had all this stuff going on.”

“For me, the meal front was where it all came crashing down,” Gustafson added. “I get home, the kids are … hungry and … everyone [is] crying. I would curse myself for … not getting the groceries, for not making something quick enough. Mealtimes were my battleground. It was really hard.”

Gustafson’s struggle with family meals eventually became her inspiration. She reached out to Moulton in 2006 and said, “Let’s do a show together.” The topic was a no-brainer as far as the producer was concerned.

“You know who your real friends are. They’re the ones who reach out to you when things head south … when you lose your dog, your dad dies, you lose your job.”

Sara Moulton

“I thought she’ll be focusing on this one issue — how working parents can get food on the table weeknights with less stress,” Gustafson said. “I thought it was a winner.”

Gourmet, where Moulton worked when the series began, liked the idea because underwriters for the TV show would also advertise in the magazine. That marketing strategy worked well for the first season, which debuted in 2008. But as the U.S. economy unraveled that fall, the show went into hiatus. Condé Nast, publisher of Gourmet, shuttered the magazine in November 2009.

“I thought, ‘Well, that’s that. We’re done with this thing,’” Gustafson said. She believed the show would never come back.

But Faison contacted Moulton after Gourmet’s demise. “I wanted to know that she was OK,” said Faison. “I called her and I said, ‘What are you doing?’ And she said, ‘Not much.’” Moulton had worked for the magazine for 25 years.

“You know who your real friends are,” Moulton said of the call from Faison. “They’re the ones who reach out to you when things head south … when you lose your dog, your dad dies, you lose your job.”

For 21 of her years with Gourmet, Moulton had what she described as “the best job on the planet.” As executive chef, she had an unlimited budget to prepare meals for Gourmet’s advertisers. She also enjoyed the educational nature of cooking for some of those events. Moulton worked within the magazine’s advertising division in a role that was completely walled off from the editorial staff.

In retrospect, she now sees that job as great training for learning to work with sponsors of her public television show.

During her run on the Food Network from 1996 to 2005, Moulton came to resent the product placements that were foisted upon her, she said. She was annoyed by the editorial control imposed by the channel’s executives.

Fun on a public TV budget

Moulton loves the control she has as co-owner of Sara’s Weeknight Meals with Gustafson. They’ve been able to place the series on Hungry, a free ad-supported streaming television channel. The show’s YouTube channel has more than 13,000 subscribers, but new episodes are no longer posted on the platform.

Through Create TV, the digital multicast service that APT distributes to public TV stations, Sara’s Weeknight Meals is also broadcast to more than 83% of American TV households.

So far this year, the first 11 seasons of Sara’s Weeknight Meals have reached 93.5% of TV households, according to Dani Cook, director of station relations for WETA in Washington, D.C., the series’ presenting station. She credited TRAC Media Services, the research company that specializes in public television ratings, for the carriage data.

Moulton said these ancillary distribution outlets are not generating much income.

“I just want people to be able to see the shows,” she said.

Despite the series’ longevity and reach, Moulton said it’s still a struggle to secure underwriting. She described Faison as dogged in her pursuit of sponsors. “She knows all the players in the food world and doesn’t give up,” Moulton said.

“We never get enough money … to shoot as much as we want, although we’ve had a lot of fun,” Moulton said.

Revelations of Italian pizza-making

One month before Gustafson converted her kitchen into a TV cooking set, she accompanied Moulton and Faison on an Oceania cruise around southern Italy. Working with a local video crew, they shot sequences on location in Rome and Parma.

On board the cruise ship, Moulton taught passengers how to make a dish called “inside-out eggplant Parmesan” and a version of cannoli in which cream is stuffed into scooped-out strawberries instead of a pastry shell.

According to Faison, Moulton’s cooking classes were standing-room only.

Staying on the ship meant that Moulton and Gustafson had a limited time to meet up with their video crew and gather footage of authentic Italian food experiences. If the host and producer didn’t make it back in time, the ship would leave without them.

“You have to set up the lighting, do the prep, rehearse, make the recipe and then clean up,” Moulton explained. “You’ve got to leave the place the way you found it. To do that in eight hours, forget about it.”

During a field shoot outside of Parma, the women stood ankle-deep in a wet, gummy layer of cow manure spread over a tomato field. They toured a warehouse where wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, each worth more than $500, were stacked 15 feet high. Moulton was bowled over by the aroma.

“I felt like I was in the motherland,” she said. “It was just heaven.”

In the upcoming season, viewers will see Moulton chowing down on a deep-fried version of pizza that Italians started making during World War II, after ovens in cities and towns across Italy had been destroyed by Allied bombing.

“Hands down, one of the best things I have ever eaten,” she insisted.

Another revelation from the show’s exploration of Naples, the birthplace of pizza: Italians don’t throw pizza dough in the air, roll it out or stretch it. They simply flip it back and forth between their hands, Moulton said.

In one restaurant shoot, with the crew rushing to finish filming before customers were let in to dine, the pizzeria’s oven had not cooled down to the optimal temperature for baking. The pies went in anyway and were done in 45 seconds.

“I can’t tell you how hot it was in that kitchen,” Gustafson exclaimed.

Despite the heat and manure, the trip had plenty of upsides. The three women have made many trips to Italy, but they discovered new treats in Rome that they had never tasted. These included an orange-flavored brioche-like bun stuffed with whipped cream called maritozzi, deep-fried rice balls stuffed with cheese known as suppli, and a sandwich made with the luncheon meat mortadella on focaccia-like bread.

Asked how long she plans to continue doing the show, Moulton replied that at this point she’s not sticking with it for the money.

“Let’s be honest, I’m not getting wealthy doing this. … I think it’s more, ‘I’m not dead yet’ — that sort of thing,” Moulton said. “Because it’s so much work, every season I go to Natalie and I say, ‘Do you really want to do this again?’ And she says ‘Yeah.’ It keeps our brains and creative juices going.” The friends and business partners are both 71 years old.

After four-plus decades in television, Gustafson said she still loves the work. “Being with such nice people, [like] Sara and Stephanie, means a huge amount,” she said. “And on top of that, to be eating delicious food every day, what’s better than that?”

Faison, who is 10 years younger than Moulton and Gustafson, said she has no plans to leave the team.

“I’m in,” she vowed. “I’m in for all of it.”

Corrections: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that Moulton cooked for guests of Good Morning America before becoming the show’s food editor and an on-air contributor. She prepped for chefs and cookbook authors who appeared on the show before becoming the show’s food editor and an on-air contributor. The article also incorrectly said that Gustafson worked for the Food Network for 20 years. She was with the network for eight years.