With Film Academy, WQED prepares students for careers in digital media

WQED Film Academy

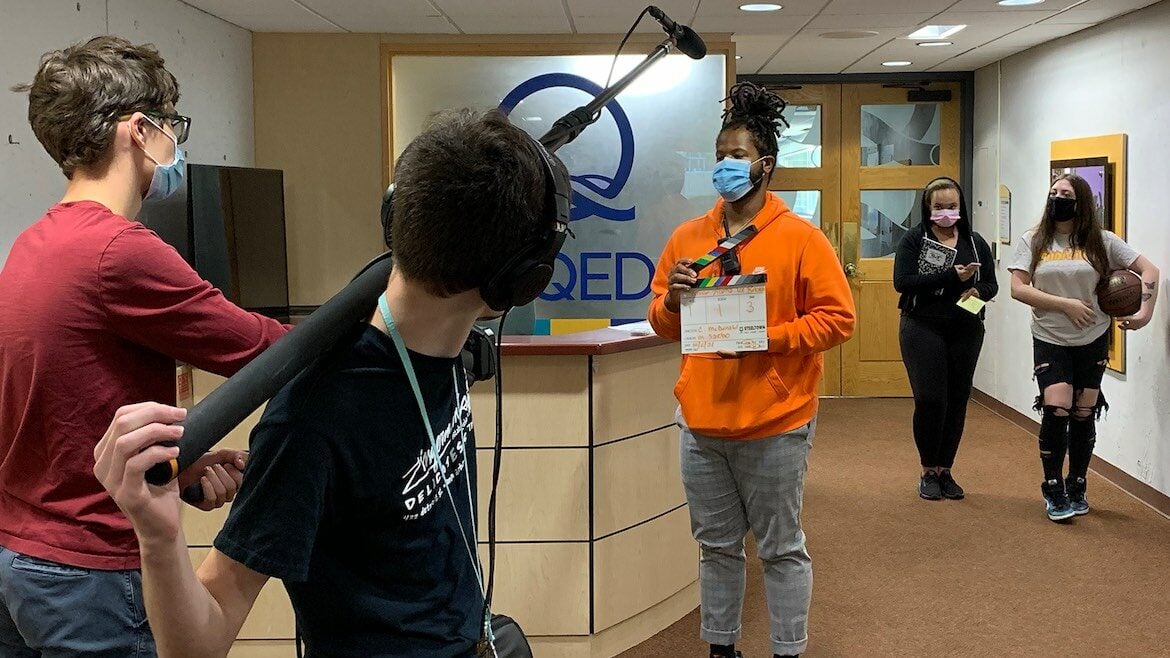

Film Academy students participate in an ice-breaking exercise during the first week of the fall 2021 session.

When high-school students Gigi Laurita and Max Mitchell entered the 48-Hour Film Project last year, they weren’t sure what kind of film they’d end up producing, but a documentary about the filmmaking process wasn’t part of their plan. Teams are assigned a genre, a character and a line of dialogue and must write, shoot and edit a short film in just one weekend.

“We didn’t end up finishing the project,” Mitchell said. “We ran out of time with our editing, so that was a little bit disappointing, but it was a fun experience.”

Months later, Mitchell and Laurita created a documentary about their experience. That film, titled Shelved: A 48-Hour Film Fiasco, is set to be screened at the All American High School Film Festival in New York City next month. It’s one of three films headed to the festival that represent Pittsburgh’s WQED and its newly acquired Film Academy. Mitchell studies digital media production at Florida State University in Tallahassee, while Laurita attends the film school at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

“A lot of my friends are very jealous that I’m going to New York City for a film festival,” said Laurita. “A lot of [my classmates] haven’t even entered festivals because they don’t have any work to show for themselves, so I’m really grateful.”

‘A perfect fit’

The Film Academy launched in 2015 under the Steeltown Entertainment Project, a digital media advocacy and training organization founded by writer, producer and filmmaker Carl Kurlander. A native of Pittsburgh, Kurlander saw the organization as a link between his hometown and Hollywood. Steeltown advocated for the Pennsylvania Film Tax Credit program, which became law in 2004, and created an incubator for independent projects in partnership with WQED in 2011.

The youth training programs came about organically, as schools and community organizations inquired with Steeltown about providing on-site educational opportunities for their students. Those efforts gradually grew to include the multitiered Film Academy, where the most advanced students are paid to pitch and produce short films. The on-site programs continue as WQED Film Academy On Location.

By 2018, the region’s film industry was thriving, and the incubator had run its course. Steeltown’s board recognized that the youth training programs were the organization’s most valuable assets. Kurlander and Steeltown amicably parted ways, and new CEO Wendy Burtner began looking to forge a partnership with a larger organization that would help maintain and grow the Film Academy and Steeltown’s other education and workforce-development programs.

At the same time, WQED’s Education Department was looking for ways to better serve teens and tweens and diversify its pipeline of young creative talents. Steeltown became a tenant at WQED’s headquarters in 2021, and a partnership started to fall into place. The station officially acquired the programming this spring.

“It just seemed like a perfect fit,” said Gina Masciola, managing director of education at WQED. “[They were] here. We really need a program that’s making the kind of impact that these guys were making.”

Out of nearly 1,000 community members who engaged with the Steeltown/WQED film programs between spring 2021 and summer 2022, approximately 727 were students.

The missing middle

A 2021 report from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop firmly established that teens and tweens are largely missing from public broadcasting’s audience. Through extensive interviews with young people in this age group, researchers found that they have little awareness or understanding of public media. As part of a CPB-funded effort to help public broadcasters more fully engage Generation Z, the center this year awarded 12 grants to stations “to create content by, with and for tween and teen audiences.” WQED’s Film Academy was among the recipients.

“One of the big challenges that we’ve seen is that stations generally don’t have youth-development expertise. … For the most part, they’re news and community-based organizations,” said Rafi Santo, senior fellow at the Cooney Center. “How do you build up the capacity to collaboratively work with young people on media is just a big question.”

WQED’s acquisition of the Film Academy is one example of how to build that capacity, Santo said. The benefits of such efforts flow not only to the students — in terms of technical skill development, exposure to career pathways, and media literacy — but also to the stations themselves. When done intentionally, involving young people in media production can breed innovation that percolates throughout an organization.

While many youth media programs are focused primarily on the training aspect, public broadcasters have a unique opportunity to consider how to serve audiences with youth-created content, Santo said.

“Certain adult audiences, it’s important for them to hear those stories — parents, school administrators, mental health professionals, et cetera,” said Santo, who spent ten years working in youth media before pivoting to research. “Then there’s the idea of producing content that has a different look and feel and perspective, and that kind of bends the age curve down.”

But Santo cautions stations against simply involving young people in the kinds of productions they’re already doing.

“It’s very intensive to do this work, so there should be something … produced that you needed to have young people involved, that it was a story that wasn’t possible otherwise,” he said.

Artists and engineers

Students enter the Film Academy at the Learning Level, where they gain basic technical and creative skills, like screenwriting, camera operating, lighting and video editing. The program is offered three times a year, in the spring, summer and fall, with both in-person and virtual options available. By the end of each session — 12 weeks in the spring and fall and six weeks in the summer — each cohort has produced its own short film.

The Academy costs up to $2,500 to attend, but adjusts its pricing on a sliding scale for qualifying students. It also awards scholarships regardless of income. As a rising junior in high school, Mariah Sanchez was paid to attend the 2020 summer session through Pittsburgh’s Partner 4 Work workforce-development program. Sanchez is now a freshman at Point Park University studying animation.

“It was a really wholesome environment where everyone can do their own thing,” said Sanchez. “You can explore the things that you like or may not like — you’ll find out. It’s just a really nice place to be creative.”

After completing the program, Sanchez returned at the Intern Level and later became part of the Teen Film Crew. Interns act as production assistants on Teen Film Crew projects. They must log 100 hours before they can become paid crew members and pitch their own projects. Members of the Teen Film Crew also take on client work, including promotional videos for local organizations and recordings of live events.

“We have our artists and our engineers,” said Film Academy Director Ian Altenbaugh, who started as a teaching artist with Steeltown in 2016. “A lot of our engineers are like, ‘I would much rather work on client stuff. I don’t have to worry about thinking about all the ideas, I can go in and just shoot,’ where we have other kids who are like, ‘I’m going to tell a story.’”

Those stories end up not only in film festivals but also on the Reel Teens YouTube page. A documentary about the local drag scene was featured on WQED’s Filmmakers Corner, a local series showcasing independent film.

‘We can reach kids anywhere’

This fall, WQED will offer the new Film Academy Lite, geared toward middle schoolers. While the program is open to any high-school student, staff found that mostly upperclassmen were signing up.

“We wanted to do what we could to engage students earlier so that they could stay with us longer,” said Film Education Director Mary Ann McBride-Tackett, who also previously worked at Steeltown. “We’ve had [students that] we affectionately call our ‘lifers,’ that’ll be with us for four years, and it’s really amazing to see those students grow.”

The program is also expanding its geographic reach by engaging students virtually, as necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We realized we can do this, we can actually teach this curriculum and reach these students and engage them virtually permanently,” said Altenbaugh. “We can reach kids anywhere.”

The Film Academy is already working with students from across Pennsylvania and plans to extend its reach nationally, according to McBride-Tackett. “This is just the beginning,” she said.

Support for young filmmakers doesn’t end after high school. WQED also acquired Steeltown’s adult-oriented programming, which includes networking events, crew referrals, workshops and one-on-one consultations.

Graduates of the original Steeltown program are now working in the industry as production assistants, including on the sets of the television remake of A League of Their Own and Pittsburgh native Billy Porter’s directorial debut, Anything’s Possible.

“Once students graduate from Film Academy, they then just become part of that filmmaking community,” said McBride-Tackett. “As they grow and learn and get life experience, professional experience, we have engaged them to come back and then work with the next generation of students.”

Correction: This article has been updated to correct details about the Film Academy program. The three sessions vary in length from six to 12 weeks, depending on the time of year; they’re not uniformly eight weeks. The cost of attending is $2,500, not $2,000, and a sliding scale is available to qualifying students based on income, not to each student. Scholarships also are available to students regardless of income. The third level of the program is called Teen Film Crew, not Reel Teen Film Crew.