How the pandemic prepared public media to build an audience-centered culture

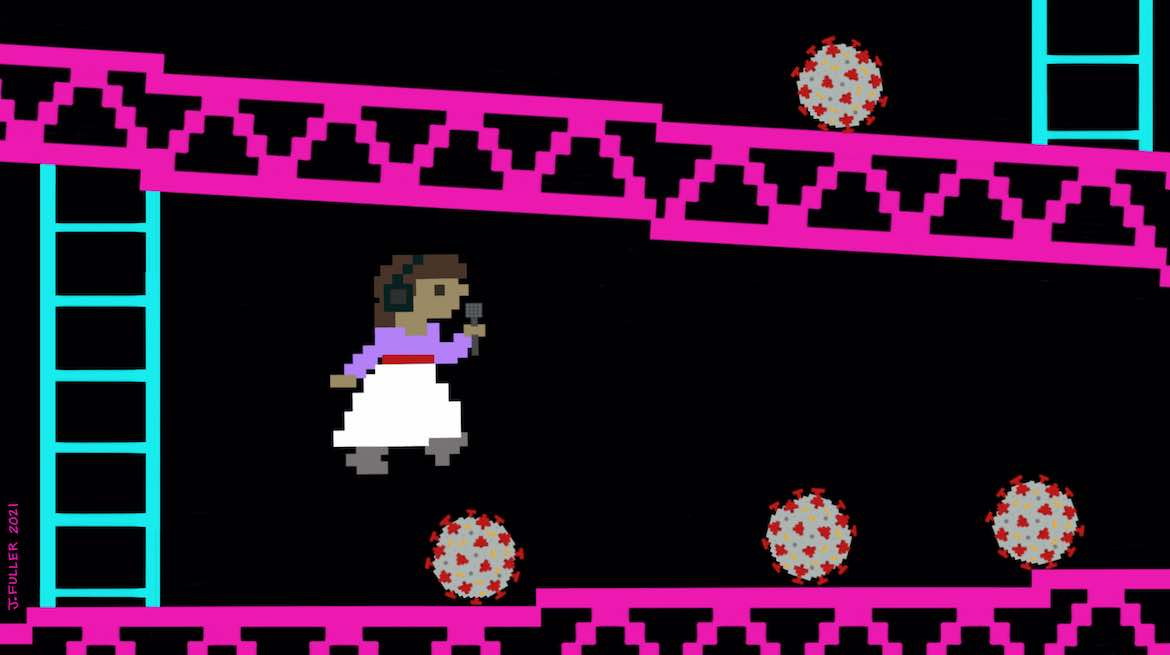

Jacquie Fuller

Over the past year, I’ve watched public media organizations meet the challenges of the pandemic by creating ways to serve audiences that would have been previously unimaginable.

From COVID help desks to the most creative examples of virtual — and newly accessible — live events, the pandemic challenged many of our organizations to set aside some of the well-worn ways we do things in order to ask a single essential question:

“What does our community need from us right now, and how can we best provide it for them?”

The process of asking and answering that question is how we develop an audience. Continually repeating this process while embodying and rewarding the skills required to meet audience needs is how we build an audience-centered culture.

Audience-centered culture will allow us to meet our mission to serve whole communities. And it’s key to our survival.

Over the many years that I have worked in this industry, nearly every public media leader has mentioned reaching younger and more diverse audiences as an important organizational goal. That goal might involve launching a project, study or strategic plan; the hiring of a charismatic leader; or all of these activities. These initiatives can succeed, but alone or in some combination they won’t be enough to meet the challenge that’s before us.

Cultural change happens when the skills, structures and incentives learned over the course of audience-building initiatives permeate into every corner of an organization. Only then will we able to become audience-responsive. That’s also, by the way, when we will become more equitable and inclusive and able to harness the vast human talent in our organizations.

The pandemic has taught us the first steps of how to do this, out of necessity.

While the past year has brought many challenges, it also pushed us to work in new ways. Let’s consider how this may have shown up in your organization:

- Did you try something you’d never done before? Was there room to experiment, learn something and try again? (In a pandemic, after all, we could hardly be expected to have all the answers.)

- Did you work with new people or new teams to get something done? Did you gain an understanding of their goals and constraints, and recognize what stands in the way of your collaborating more often? Did you collaborate in different ways that bridged the content/revenue firewall?

- Did you learn how to do something outside of your department or expertise? Did decisions happen top-down, or was there new flexibility in your organization’s hierarchy to allow for good information to travel in any direction?

- Did data or insight from your community drive some of your decisions? Did you take direction from your community in a new way? Did you truly collaborate with an external partner you knew could deliver expertise that your organization could not?

- Did you see more of your colleagues’ full selves, with compassion — even admiration — for whatever complexities were present in their lives? Did you learn from colleagues’ lived experiences and did that affect how you approached something as a team?

- Did you learn something new about unearned privilege? Did you notice biased thinking in yourself and attempt to question it? Did you try speaking up for yourself or on behalf of someone else when something wasn’t right? Did you think of an audience segment in a way that conferred new value?

We often talk about “change management” in organizations with an assumption that change is what happens between point A and point B. We start somewhere, we know where we need to go and we get to where we thought we were going. We assume there will be an attempt to minimize discomfort along the way.

But the pandemic forced our organizations into a state of constant change. We’ve had no clear single destination, no timeline. It’s been uncomfortable, to be sure. And while many of the particulars (parents working without child care, physical isolation, no boundaries between work and home, to name a few) were unsustainable from the start, we have collectively adapted using some of the skills we need to sustain and progress through the discomfort that comes with working in a state of change.

An audience-centered culture thrives in a constant state of change.

Not everyone wants to participate in such a culture. Not every leader will be willing or able to guide the organizational growth required to create this change. Building an audience-centered culture requires an all-in effort and investment, at every level of the organization. It starts, but does not end, with leadership. Consider the pandemic-era experiences I outlined above, and imagine all of them amplified and normalized within your organization. Imagine each individual in the organization embracing these kinds of organizational values.

I look forward to exploring the markers of an audience-centered culture in the coming year through webinars, cohort discussions and trainings from Greater Public. We’ll begin with a two-part webinar series on June 30: “Building an Audience-Centered Culture: A Case Study From KERA.” And this year’s virtual Public Media Development and Marketing Conference July 13–22 will include many sessions and keynotes that tackle this topic directly.

It’s not only what an organization accomplishes as it adapts to changing audience needs — it’s also how an organization does these things. Leadership needs to become less hierarchical and more accountable. Staff will need to be stronger partners with greater adaptability. We can no longer take our exceptionalism for granted. But we can learn to trust one another more deeply and, more importantly, trust in the audiences we aspire to serve to lead the way.

Joyce MacDonald is president and CEO of Greater Public, a professional development association for public media fundraising and marketing.