How public broadcasting overcame early setbacks to become a national institution

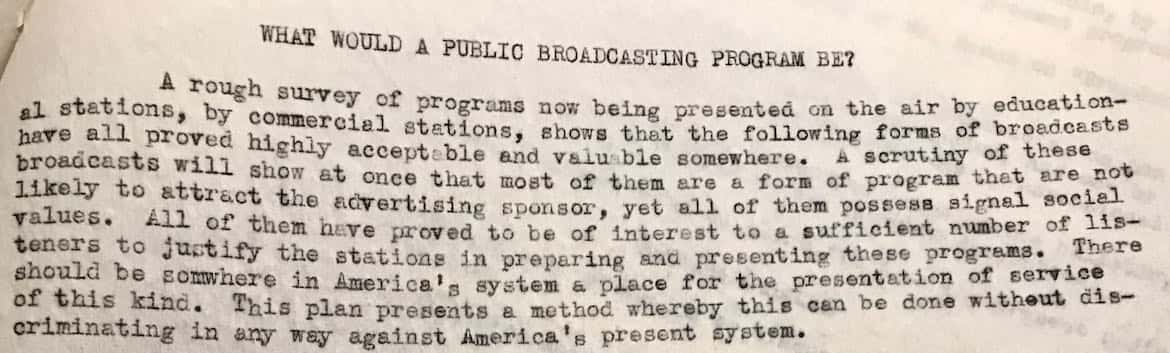

The first institutional use of the term public broadcasting, around 1936, as an educational service that provided entertainment and public forums beyond audio instruction. From a proposal for regional services instead of just singular university broadcasts.

The educational mission of public media remains its backdrop. It is a free informational service that endeavors to reach every possible listener, for the purpose of informing, introducing different perspectives and beliefs, and providing an active medium for up-to-the-minute analysis. At times it has struggled to meet its ideals in practice, but that we have a legacy institution designed to follow a mission statement, and not merely seek profit, remains a major contribution to democratic discourse.

The Carnegie Commission is often credited for the “public” of public media due to its 1967 report Public Television: A Program for Action. The coinage finds its roots in the decades-long educational media reform movement, which grew from scattershot classroom instruction broadcasts in the 1920s to encompass federal, public, educational, academic and to some extent even commercial broadcasting proponents during the 1930s.

As self-evident and uncontroversial as the belief in equal access to information sounds within the noncommercial media sector itself, politically the concept always faced resistance. Originally excluded from the Public Television Act, radio was brought into the bill in the last instance, resulting in the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. National Public Radio was finally constituted in 1971 out of the talent of a tenacious and decentralized university network that had been based at the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, a trade organization that was founded in 1925 and disbanded in 1981.

Fast forward to 2021, and the origin of public broadcasting looks something like a social movement. Tens of thousands of producers, hosts, engineers, archivists and administrators worked in parallel for decades, bound by belief in the capacity of media to provide equal access to information across demographic affiliations, through nonprofit production and a public service orientation. These concepts were famously canonized 50 years ago in Bill Siemering’s remarkable original mission statement for NPR, which was written 50 years after educational radio first materialized.

Crucial to this history, it took decades for practitioners to crystallize the relationship between the concept of what noncommercial media might contribute to democratic deliberation, and programming that was actually of interest to audiences. Well known in the lore of the noncommercial media sector, the first wave of educational broadcasts in the 1920s were almost entirely composed of microphone instruction, as lectures recited to a largely indifferent audience. Great strides were made in combining education and performance between the 1930s and the end of the 1940s, and by the 1960s early educational content such as home economics, journalism, farm reports, public forums and music appreciation had evolved into proto–public media programming that was both informative and entertaining.

The impact of early media regulation

While educational broadcasters honed their craft, the sector was supported by a broad political lobby that played an important role in raising public awareness about the benefits of democratic media. It was educational radio’s early trade organizations who initially articulated the philosophy of the nonprofit concept while broadcasters learned to formularize radio craft. A member of one trade activist group in particular — the National Committee for Education by Radio (NCER) — used the term “public broadcasting service” to persuade regulators that a “public” access point for universal education could be achieved through radio technology.

In the early 1920s, the first noncommercial broadcasters took their cue from the relatively new practice of compulsory education in the “modern school” and believed that creating an ethereal “social center” would encourage a civic-based democratic sphere in promotion of social equity. From the beginning, educational broadcasters emphasized two recurring mission statements: first, that educational radio should be a nonprofit institution, and second, that its purpose was to serve under-represented populations.

In its nascent state, educational radio was strong in belief but weak in pursuit. Educational radio was so poor at teaching agrarian populations that in 1933 the U.S. Department of Agriculture distributed a departmental report titled “Educational Broadcasting in 1928-1933” that painted a grim picture of its performance. “Previous hopes surged high,” the report stated, but by 1933 the poor quality of educational broadcasts had “exploded” the department’s belief that radio had “magical powers of education.” Yet the principle of equal access remained persuasive.

In 1927 U.S. Commissioner of Education William John Cooper participated in a series of meetings that addressed the deficiencies of educational radio stations, leading the Carnegie Fund to hire educator Levering Tyson to form a collaborative National Advisory Council on Radio in Education. Cooper also inspired the formation of NCER, a lobby group that had close ties to the National Education Association, the Office of Education, the state of Ohio and the Payne Fund, a philanthropic organization in Ohio that underwrote educational film and radio experiments in the 1930s. While NACRE collected information about the educational radio landscape, NCER found initial success by lobbying that 15% of all radio channels be set aside for educational use. That gained the support of Ohio Sen. Simeon D. Fess, who proposed a bill for experimental frequencies. But the bill failed.

In spite of a groundswell of philanthropic and public sector support, NCER and NACRE chalked up a string of defeats between 1928 and 1933, until the Communications Act was passed in 1934. The Act consolidated a trajectory for American media friendly to commercial radio, stripping educational stations of their licenses based on what policymakers called the “public interest” mandate — basically, that broadcasters were more responsible to the technical practices of broadcasting than to any social ameliorative content. The inevitable aftermath of the Act was, as Robert McChesney details in his book Telecommunications, Mass Media, and Democracy, that over 80% of university broadcaster frequencies were redistributed to commercial stations.

The unexpected outcome was that instead of eliminating noncommercial media, the Communications Act inspired more advocates to work for media reform. By articulating the first institutional standards for sound broadcasting practice, the Act’s “public interest” language provided a much-needed framework for educational advocates to plot their next steps. Noncommercial media had surfaced with a different concept about the purpose of media than the commercial networks. And after 1934, adherents envisioned a path by which they would remain loyal to their institutional principles but with better attention to the best practices of broadcasting itself.

Within one year of the Communications Act, FCC commissioners were already at work mitigating the effects of the Act on universities. Judge E.O. Sykes, one pre-Act regulator, migrated to the new FCC. Subsequent to the Act, Sykes issued a Pursuant (regulatory statement) as FCC chairman that advised educational stations to take seriously that radio required more than reading into a microphone, including research into the aesthetics of broadcasting itself. Sykes began to work with new Office of Education Commissioner John Studebaker, and together they formed a Federal Radio Education Committee, which put public, federal, educational and private media discourses into conversation.

NCER initially held out hope that it might continue with Cooper’s original vision for set-aside frequencies. However, this plan was brought to a halt when it was revealed that a third trade group of educational broadcasters, the Association of College and University Broadcasting Stations (ACUBS), had rejected frequencies for a new protected 1500–1600 AM bandwidth, due to concern that radio receivers were not yet equipped to tune in to those signals. Once it had been revealed that reserved-channel lobby strategy was not only defeated in the Act but had been inadvertently undermined by educational broadcasting practitioners themselves, the early form of NCER collapsed.

Transforming lobbying into system building: Rocky Mountain Radio Council

Out of the ashes of the previous NCER, one member, University of Wyoming President A.G. Crane, decided to change course from political lobbying and call upon new “public interest” rules to instead build a sustainable alternative to commercial broadcasting. Crane’s vision was to equally meet Sykes’ Pursuant while observing the philosophy of noncommercial media. This meant paying closer attention to the standards of broadcasting practice itself. It was not enough to lecture into a mic, he concluded — listeners must feel as though they were tuning into a service “vital yet subordinate and incidental to consciousness.” Educational broadcasters weren’t just defeated by commercial broadcasters; they had failed to appeal to their “unseen audience,” and the key to their survival would include devising a plan to “conserve radio for public services” among national, regional and state boards. In 1936 Crane announced that NCER planned to begin an educational network that emulated the best practices of the private system but that would be controlled by nonprofit stakeholders.

After the Act, Levering Tyson of NACRE applied for and received a grant from the Rockefeller General Education Board to hold a FREC-connected conference on whether the 15% proposal was still viable and whether the proposal met the mandate of “mutual cooperation” stipulated by Sykes’ Pursuant. In the process, Tyson persuaded the Rockefeller Foundation to underwrite future educational radio research. Crane applied to fund construction of the Rocky Mountain Radio Council, a regional network that would cover the Rocky Mountain region as well as western Kansas and Nebraska. RMRC was based out of the University of Wyoming, with offices in Denver. In correspondence Crane repeatedly referred to his service as “public radio,” a “public broadcasting service” and “public broadcasting,” setting the first use of the term in American media.

RMRC was granted provisional Rockefeller Foundation funding in 1937, and by 1940 RMRC was held up by FREC as the exemplar of a successful educational radio network. RMRC hired professional DJs, programs were put though research and development, programs were reliably scheduled, and similarly to the national networks, RMRC implemented best practices for transmitter, wire and shortwave maintenance. By 1940 RMRC implemented the first organized use of educational record distribution, which at the time were called “program transcriptions.” Within four years Crane connected disparate listeners into a common regional curriculum, in the process becoming the first sustainable noncommercial service supported by a philanthropic fund.

RMRC’s “public” radio programs would go on to cast a long legacy in educational media history. Robert Hudson, a key RMRC employee, went on to work at the University of Illinois and participate in the Allerton House Seminars in 1949 and 1950. Out of the seminars, Hudson and Seymour N. Siegel of WNYC were appointed to construct the “bicycle network” for the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (formerly ACUBS), now widely regarded as the founding service of public media itself. NAEB applied the program transcription and relay practices that Hudson brought from RMRC.

Crucial to the history of public radio, the mission statement of noncommercial media was present at its inception, but not widely adopted until after it was shown that infrastructural implementation was not only possible, but sustainable, through reform strategies that centered on producing quality radio. The “public” of public media got its start as activist nomenclature that combined political discourses in public education, regulatory language of the public interest, and a philosophical fidelity to public service, into an active network funded by philanthropic and university-based sources. By the time educational radio and television graduated into a federally funded agency, it made good sense to pay respect to its roots with a “public” gesture.

Josh Shepperd is an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and the Sound Fellow of the Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board. He is also faculty curator of Current’s series Rewind: The Roots of Public Media.