Lorenzo Milam, legendary pioneer of community radio, dies at 86

KRAB Archive

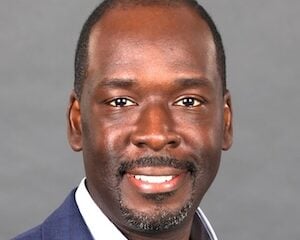

Milam at the console at KRAB in 1963.

“A broadcaster should be encouraged to be experimental.” — Lorenzo Milam

Lorenzo Milam died July 19 in Pueblo Escondido, Oaxaca, Mexico. He was 86. He was a leader in disability rights, publishing and half a dozen other pursuits.

But in community radio, Lorenzo was a legend in his own time. He inspired hundreds of people to start community radio stations all around the country, myself included, and has left us a raucous and sprawling living legacy.

Lorenzo was one of the most influential and inspiring characters ever to sit behind a microphone. Through his playful genius and uncompromising commitment to the First Amendment right of free speech, Lorenzo was in large part responsible for creating a national movement that launched hundreds of grassroots stations, touched thousands of lives and warped the shape of public broadcasting forever.

Lorenzo learned basic operations at his college radio station, but it was his discovery of KPFA, the original Pacifica station in Berkeley, Calif., that transformed him from a DJ into an iconoclastic radio pioneer.

He was so captured by the unique pacifist programming and listener sponsorship of KPFA that in 1958 he tried to start a Pacifica-like station himself in Washington, D.C. When that didn’t work out because the FCC was fearful of a Pacifica voice in our nation’s capital, he fled to Seattle. There he was able to fulfill his dream of a freeform, anti-commercial station — KRAB. (Pacifica eventually did get that license for Washington, D.C, and WPFW went on the air in 1977.)

With the help of gifted mad-scientist engineer and partner-in-crime Jeremy Lansman, KRAB went on the air in 1963 and was the first non-Pacifica station to offer a really broad and quirky range of voices, music and culture over the airwaves. “Lorenzo was an incredibly patient mentor,” said Chuck Reinsch, KRAB’s general manager. “He shared his dream and made the effort and the struggle to achieve it appealing.”

In the ’60s and ’70s, the country was roiled by the civil rights movement, Watergate, growing opposition to the war in Vietnam, and the revolution in norms that brought about the counterculture and Woodstock Nation. So while CPB, created in 1967, was aiming to professionalize “educational” radio, Pacifica stations and KRAB were pumping out sounds and voices that reflected a very different politics.

At the time, frequencies on the educational portion of the FM band were relatively available, and the actual process to apply for a noncommercial license was technical but not difficult. Lorenzo recognized it was a moment ripe with the possibility of filling the spectrum with more “alternative” radio stations.

Always a prolific writer, he produced a slim booklet called Sex and Broadcasting: A Handbook on How to Start a Radio Station for the Community. It was a straightforward step-by-step guide for how to find a frequency, set up a local organization, fill out the FCC application, wait a year for a construction permit, and then, once it was all assembled, put the most outrageous programming possible on the air.

The pamphlet was an underground smash, and Lorenzo produced a second edition of Sex and Broadcasting in 1974 as an actual book (Dildo Press; with 20 pages on How to Start a Station and 300 pages of his musings and essays from the KRAB Program Guide).

This edition became the iconic publication of community radio. In short order, local groups began to apply for radio licenses and be granted construction permits everywhere – Pittsburgh; Cincinnati; Denver; Dallas; New Orleans; Atlanta; Minneapolis; Salt Lake City; Lincoln, Neb.; Tampa, Fla.; Madison, Wis.; Austin, Texas; Little Rock, Ark.; and Portland, Ore., as well as small towns like Telluride, Colo.; Park City, Utah; and Provincetown, Mass.

Through Lorenzo, these groups were in close touch with each other, and soon it was apparent that a critical mass of station projects was underway.

I’ll be showing my age here: This is the period when I was seduced by community radio. I was a student at Antioch College, and my personal interest in sociology and mass communications brought me to WYSO, the campus station. Though not a community licensee, much of the programming was produced by local volunteers, and the college itself was becoming a hub for alternative media — not only radio, but also film, video, photography and journalism.

It was here that I first heard of The KRAB Nebula tape exchange, ¼-inch audio tapes that were being sent between stations to share programs, which we aired on WYSO. It was also where I met Jeremy Lansman, who put a copy of the Sex and Broadcasting booklet in my hands.

After graduation, I moved to Cincinnati with some other Antiochians “to start a radio station.” Stepchild Radio of Cincinnati Inc. received a construction permit in 1974, and in 1975 WAIF hit the airwaves, the same week as WORT in Madison (we had a friendly rivalry with them to see who would get on the air first). Having an actual voice on the radio dial — it was very exciting!

I met Lorenzo in person early in 1975, when he invited a couple dozen radio projects to meet at the KRAB firehouse studio. An organizing effort ensued, which led to 80+ radio-activists showing up in Madison that summer for NARK, the National Alternative Radio Konvention.

Lorenzo shared his vision at NARK: “This is where the real community radio idea emerged: one that depends on hordes of volunteers and constant influx with freeform rambunctious, tearing-up radio, finally torn away from the pale gray shadows that had encumbered educational radio in the United States for 40 years.”

It wasn’t long after that a dozen stations convened in Cincinnati, hosted by myself and WAIF, with the express purpose of creating a national organization. At the end of the weekend, the National Federation of Community Broadcasters was formed, and Tom Thomas and Terry Clifford, fresh from Lorenzo’s station KDNA in St. Louis, were headed to Washington, D.C., to set up shop.

The scores of stations that were built in the ’70s and created NFCB represented a second generation of community radio modeled on KRAB and Pacifica. A third generation of stations signed on in the next decade, including many minority projects such as Native American stations and Radio Bilingüe, which created their own model for funding and program production. Most but not all of these outlets are still on the air.

The fourth generation of stations is one of the more dramatic developments in public radio — the creation of LPFM, the low-power radio service. Now boasting hundreds of stations, LPFM is the brainchild of Pete Tridish, a broadcast engineer and former pirate radio DJ who clearly credits Lorenzo. “I only met him once, but Lorenzo wrote the blueprint for my life in Sex and Broadcasting,” Pete said.

Lorenzo’s vision for community radio rested on willing volunteers to run the station, in front of and behind the microphones. As Gray Haertig, another engineer, tells it, “I walked into KRAB in 1966, at the age of 16, and the odd, bespectacled man with thein quiet, amused voice and crutches gave me a job as the Monday night announcer, mainly because I could pronounce the weird names of the (frequently) weird classical music that was interspersed between all the other weird stuff throughout the day. Unbeknownst to me at the time, my life’s trajectory had been set.”

I have to share one more event in Lorenzo’s legacy: The Lansman-Milam Petition.

Lorenzo and Jeremy were always looking for ways to poke the bureaucracy at the FCC and challenge the rules. In 1974 they became alarmed that the proliferation of religious radio stations across the noncommercial band, along with multiples of university-owned licenses, wouldn’t leave any room for new community applicants.

They submitted RM-2493, a Petition for Rulemaking at the FCC that requested a freeze on issuing new construction permits within the noncommercial band until the FCC could determine clear criteria for who could apply for these restricted frequencies.

Whether they planned it or not, they unleashed such a firestorm at the FCC that the Commission has still not recovered.

The lawyers for many of these religious broadcasters saw the petition and immediately declared that it was an effort to end religious broadcasting. The stations urged their listeners to write to the FCC and insist these godless heathens not take their stations off the air.

The FCC received more mail on this subject than any other in its history. Literally millions and millions of form letters and postcards poured in from churchgoers around the country. There was also the false rumor that the notorious atheist Madeline Murray O’Hair was behind this plot to shut down religious radio.

To set the record straight in his own fashion, Lorenzo published The Petition Against God, but this particular rumor has persisted over time, and periodically even now the FCC receives new mounds of mail.

Radio waves never die. So Lorenzo’s voice is still going out into space, urging us to be outrageous. Lorenzo did many other things with his life after he left community radio, but his greatest legacy will be that he inspired thousands of regular people to transform the airwaves and make them their own.

Nan Rubin has been a community media organizer and activist for more than 40 years. With a particular focus on policy and technology, Nan helped create both the contemporary movements for media justice and media reform. She built community stations WAIF in Cincinnati and KUVO in Denver, and she was a founding member of NFCB and AMARC, the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters, based in Montreal. She lives in Las Cruces, N.M., where KTAL-LP, her latest station project, has been serving 100,000-plus people in the Mesilla Valley for three years.

Well done, Nan. Thanks.

///Jon Gallant, ancient mariner of the KRAB Nebula

Thanks, Nan. KRAB was my constant companion when I lived in Seattle 1969-1972.

I think all surviving copies of Sex and Broadcasting (including mine) are severely dog eared as in the photo. Lorenzo is in heaven for sure.

Thank you Nan! Dunno how I missed this in 2020 but glad to catch up. I knew Lorenzo had passed. Good for Currents for acknowledging him (and you!). Someone somewhere should do a doc about this whole movement.

I’m Shedding a tear.

Thanks, Nan! Sorry I didn’t catch this when it first came out, but kudos to you for giving proper recognition to the godfather of community radio, Lorenzo Milam. From 1972 to 1975 I was at KUSP (88.9) in Santa Cruz, CA, which was one of Lorenzo’s best step-children. We didn’t have any recorded material at the beginning, so about once a month I would drive over the hill to KTAO in Los Gatos to borrow a big cardboard box full of vinyl record albums, chosen by Lorenzo, to distribute among my DJ’s. He was often there himself, and would fill my head with useful, trenchant, and quirky information to keep our little station on track. He was our doula (midwife) and friend, and my no. 1 mentor. RIP, LWM