How the Works Progress Administration played a critical role in WNYC’s history

Courtesy The New York Times

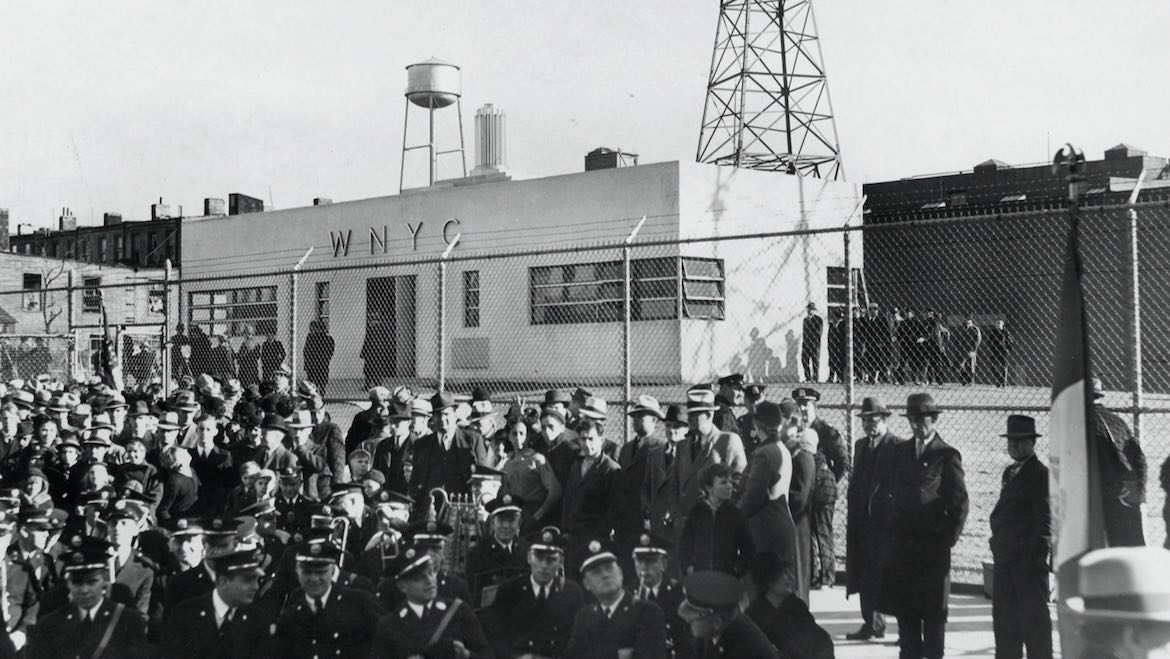

A crowd gathers for the opening ceremony for WNYC’s new transmitter site in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, Oct., 1937.

During the Great Depression, the federal government and its alphabet recovery agencies played a significant role in the survival and revitalization of WNYC in New York City. Works Progress Administration divisions funded new studios and a state-of-the-art transmitter site. They underwrote the production of thousands of hours of music, drama and public affairs broadcasts. The federal government even commissioned and installed major artworks at the station. Without this assistance, it is unlikely WNYC would have survived the nation’s economic troubles or its own.

Popular accounts tend to credit New York City Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia with being WNYC’s champion. After all, he read the comics to the city’s children over WNYC when the newspaper deliverymen went on strike in July 1945. His acting-out of Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy is, no doubt, the station’s most iconic sonic legacy. Lesser known is his ordering of a daily series during the strike known as the “Comic Parade,” featuring personalities from the popular NBC program Can You Top This reading from the funny papers as well.

But initially, the “Little Flower” was anything but cordial toward the station. When running for office in 1933, the former congressman announced a 10-point cost-cutting program of reforms. The abolition of WNYC was number nine on the list.

The station had indeed lost its way. Its original “first on the dial” frequency at 570 AM was gone, a casualty of political fighting, mismanagement and neglect. And some observers felt a pallor of civil-service routine had descended upon the ether at the station’s reassigned 810 AM frequency, restricting broadcasts to daytime-only. In 1931, noted historian Thomas Flexner, then working for the city’s noise-abatement agency, described the station’s corridors as “filled with suicidal emptiness.”

The new mayor was outwardly hostile to the station. Encountering an older WNYC mic on the podium at the Commodore Hotel, he ordered, “Get that damn peanut whistle out of here!” And true to his campaign promise, after being sworn in Jan. 3, 1934 (broadcast over NBC and not WNYC), La Guardia ordered WNYC’s future director, Seymour N. Siegel, to “go across the street and close down the joint.” The “joint” was WNYC. But after carefully surveying the situation, Siegel determined there wasn’t anything a little proper management and TLC couldn’t fix. WNYC was on probation.

With experts impaneled, a thorough study was ordered. Recommendations were made and taken seriously. But above all, between La Guardia’s first and second terms, it was the availability of federal funding that turned the mayor from a disparager of the station to its chief advocate. The WPA and its various divisions all played a critical role in WNYC’s turnaround.

The Federal Music Project

Seymour Siegel moved quickly. Barely a month had passed, and well before the blue-ribbon panel’s study was done, he got federally subsidized musicians into the studio. The first group was a string trio performing a medley of tunes from Victor Herbert’s Naughty Marietta. Within three years, WNYC would report just over half of its programming was WPA-sponsored, the majority music.

These broadcasts included at least a dozen different ensembles, among them the WNYC Concert Orchestra, the Amsterdam String Ensemble, the Manhattan Chorus, the Municipal Dance Orchestra, the Morningside String Trio, the Capital Dance Orchestra (which consisted of blind musicians), the Waverly Brass Band, the Brooklyn Symphony Orchestra, Juanita Hall’s Negro Melody Singers and the New York Civic Orchestra. Many of these groups recorded 16-inch transcription discs that were pressed and distributed by the WPA and mailed to hundreds of public and commercial radio stations around the country.

By September 1939, the WPA’s annual report noted that the the Federal Music Project’s aim to put unemployed musicians back to work accounted for nearly 85% of all music performed on the station. At the close of 1940, some 1,100 hours of these broadcasts had aired on the station that year. Seymour N. Siegel wrote that while the FMP helped WNYC, “WNYC, in turn, has unquestionably brought infinitely larger audiences than could ever be crowded into a concert hall. In the program of educating the listening public to the appreciation of the higher type of music, WNYC has done its part.”

WPA music programing on WNYC also provided a platform for discussions about music, music education and the premieres of new works. In 1939, composer Roy Harris presented 30 illustrated lectures titled Let’s Make Music under the auspices of the WPA Composer’s Forum Laboratory. The series dealt with the fundamentals of composition and attracted widespread attention. More than 1,300 listeners requested mimeographed copies of the lessons to assist with their studies.

That same year, WNYC’s World’s Fair studio played host to WPA Composer’s Forum concerts and a composer roundtable. During WNYC’s second annual American Music Festival in 1941, the WPA program assisted with an orchestra of 100 musicians drawn from the WNYC Concert and New York Civic Orchestras. Among the composer-led works was Philip James’ satirical suite Station WGZBX and the world premiere of Morton Gould’s Spiritual for String, Choir, and Orchestra. Deems Taylor conducted his composition The Highwayman, with Richard Hale singing baritone. With the U.S.’s entry into World War II, WPA funds were cut significantly and the program ended by June 1943.

New studios and transmitter site

In 1935 the station’s Chief Engineer Isaac Brimberg and his crew began drawing up plans for rebuilding the station’s studios and relocating the transmitter to a site across the East River in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. The station’s first antenna, stretching from the top of the Municipal Building’s tower across its northern wing, was far from ideal. Initially put in place with the 570-kilocycle AM frequency in mind, the “inverted L” antenna was long subpar. Additionally, the location on the Municipal Building in downtown Manhattan with its structural steel was another broadcast liability. Once finished, the new antennas were two grand 304-foot towers that the Christian Science Monitor wrote were “ready to send the voice of WNYC around the world. Each one of these towers resembles the famous Eiffel Tower of France.”

Indeed, Mayor La Guardia had plans of broadcast grandeur that dedication day, Halloween 1937. Proud and beaming, he described the new WPA-built facility as technically “right up to the last minute.” As such, he argued that it had set the stage for WNYC to become the flagship station of a new noncommercial cultural radio network of educational and public stations. The new studios, too, reflected this forward-thinking, as they were capable of feeding out as many as six different channels of content simultaneously to four different radio stations.

The economic factor underpinning this prophetic proposal was the distribution of programming by shortwave rather than costly landlines. La Guardia was planning on getting around the pre-satellite era dependence on landlines controlled by the telephone company. He said that being forced to use landlines was “as unreasonable to say that one isn’t permitted to fly from here to Chicago because there are roads going from here to Chicago.” The FCC, despite his lobbying efforts, did not agree. The signal quality of programming retransmitted via shortwave was just not good enough when compared to landlines. Still, it was a vision of WNYC few, if any, would have predicted from Mayor La Guardia 3 1/2 years earlier.

While music made up the majority of the WPA broadcasts on WNYC, non-music programming involved a wide variety of content. Series included New York Panorama, Symphonic Drama, What is Good Art?, The Streets of New York, Pals of the P.A.L. and The Human Side of Art, an unusual effort to consider artwork on the radio. The broadcasts were produced by the Index of American Design and featured the poet Louis Zukofsky as their art and design expert.

The Federal Art Project

Under the WPA Federal Art Project, four murals and one sculpture were commissioned, hung and dedicated at WNYC. At the time, the WNYC murals created a bit of a controversy because the works were all abstracts. Best known among the muralists was Stuart Davis, a leading proponent of abstract art. Speaking at the mural dedication ceremony Aug. 2, 1939, he praised the city for being open to new ideas. “I say it is of crucial importance when a city institution like the Municipal Broadcasting Company comes forward in sponsorship of abstract art,” he said. “It is in harmony with the broad democratic cultural policy of WNYC.”

Davis’ 11-by-7-foot painting hung in WNYC’s Studio B. With antennas and waves, it pulled together images of radio and sound equipment. A very stylized saxophone represents music. Since 1965 the work has hung at the Metropolitan Museum.

Other completed murals were by Jon Von Wicht (now at the Brooklyn Public Library), Byron Browne (now at the Supreme Court of New York, Staten Island), and Louis Schanker (in situ on the 25th floor of New York City’s Municipal Building). The last contribution unveiled and dedicated in August 1939 was a cast aluminum sculpture, “Harpist” by Max Baum. It is the one work of art that remains on display at the station to this day.

Two additional murals were commissioned but never finished or hung. They include a series of sketches by Lee Krasner and a two-panel work by Louis Ferstadt.

There can be little doubt that in 1934, La Guardia and his staff recognized the nascent power of radio. After all, the president of the U.S., a good friend of the mayor, was using radio to significant effect in getting his message across to the American people via his “Fireside Chats.” Still, the WPA, coming along when it did, was timely. It provided the wherewithal to improve facilities, transmission, programming, and perhaps most importantly, a change of heart by Mayor La Guardia. Without it, WNYC may have become little more than a footnote in the history of public broadcasting.

Andy Lanset is founding director of the New York Public Radio Archives (WNYC/WQXR). He has worked in public broadcasting as a reporter, producer, engineer and archivist for the last 35 years.

This essay appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, Current’s series of commentaries about the history of public media. The series is created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the RPTF, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu