How France’s national broadcaster bolstered U.S. public radio in its formative years

1 - Usb

In summer 1949, Variety magazine saluted the French national broadcaster Radiodiffusion Française for accomplishing a minor miracle. For the first time, Americans across the United States were regularly listening to French radio programs.

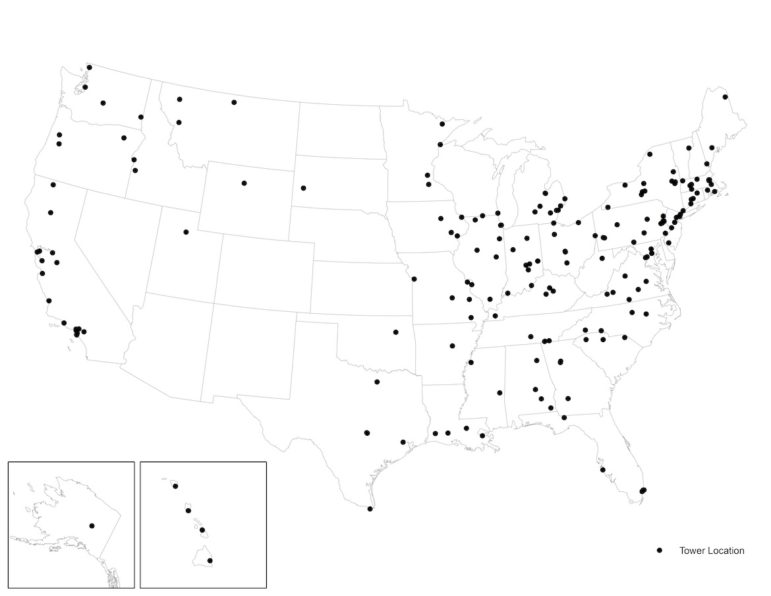

Two hundred stations, many of them independent, aired up to five weekly series supplied by the French Broadcasting System in North America (FBS). Produced in Paris with English-speaking announcers, these shows reflected an unlikely alliance between French and American producers, talent, and U.S. independent broadcasters seeking variety and access to international programs. Variety credited French broadcaster Pierre Crénesse for diversifying U.S. radio. Crénesse “demonstrated a rare talent for providing American stations with French programs that have the rhythm of American radio, without sacrificing either the cultural context or their national flavor.” To accomplish the feat required transatlantic cooperation and imagination to overcome the daunting cultural and technological challenges that had previously constrained regular transatlantic broadcast exchange.

Decades before satellite television and the internet, radio, the world’s first instantaneous mass medium, catalyzed new processes of cultural production, consumption and communication on an international, even global, scale. The history of transatlantic ties between U.S. broadcasting and the BBC is familiar to Current readers. Less well-known, however, is a history of sustained interaction between France and America occurring between 1931, when regular U.S.–French transatlantic broadcasting began, and 1974, when France dissolved its public broadcast monopoly. The story adds a forgotten chapter to the long history of radio in the U.S. by tracing the medium’s transnational ties and important relationships beyond the Anglophone world, which enhanced the cosmopolitan features of contemporary U.S. public media.

During the 20th century, political and cultural differences constrained the nature of the broadcast ties between these two allied but dissimilar nations. In the climate of the Cold War, however, U.S. support for the rebuilding and political stabilization of Western Europe dovetailed with France’s desire to restore its international reputation after the German Occupation of 1940–44. Radio broadcasting served as a mechanism of partnership that would have ancillary benefits for resource-strapped independent and fledgling public radio stations across America.

Sound-on-disc transcription recordings had emerged internationally before World War II as a means to capture events instantaneously for later playback. But such transcriptions lacked durability, and using prerecorded material on commercial network radio remained anathema for a medium that sold its audience on liveness and needed to maintain productive relations with unionized studio bands and orchestras. Independent broadcasters, both commercial and noncommercial, survived on shoestring budgets relative to the networks. Flexible by necessity and thirsty for content, such stations also attracted listeners open to experimentation who sought alternatives to the hit parade and hackneyed sitcoms and soaps. WNYC, New York City’s municipal station, embodied independent habits of mind that extended to seeking international programs for its cosmopolitan listenership.

After the Liberation of Paris, the RDF established its first New York bureau and sent Pierre Crénesse to scout opportunities for producing and distributing French content in the U.S. After a few false starts, Crénesse formed an advisory body of U.S. broadcast experts that included WNYC’s Seymour N. Siegel, a dynamic force shaping public radio in postwar America. The group contributed know-how and expertise as Crénesse and his associates shaped plans for a successful rollout of programs.

The dream of routine U.S.–French radio connectivity came to life with the bold decision to abandon transatlantic shortwave as a mechanism of feeding content from Paris to New York and create instead a “wax net” — that is, a distribution network of prerecorded programming. The humble transcription disc furnished the technical workaround. It could be pressed into service, literally, to bring French sounds to American ears. In Paris, French and U.S. staff worked together to write, produce and cut transcription recordings in the studio. These would be whisked to New York for transfer to a pressing disc that could be used to generate hundreds of 33 rpm vinyl copies for distribution via mail.

But what about the cost? In the past the RDF, a public system, had lacked resources to devote to extensive programming to America. Likewise, commercial U.S. broadcasters balked at taking on risky foreign content. In the political climate of the early Cold War, however, with the United States eager to keep France on its side, U.S. State Department officials approved the release of Marshall Plan funds to support French governmental efforts to upgrade France’s broadcasting infrastructure and to support transatlantic outreach.

The unique selling proposition of the wax net extended beyond the attraction of an infusion of five original English-language series produced in Paris. Because of governmental financing, the discs could be supplied at no cost to U.S. stations. This was sweet music to educational, independent and public programmers’ ears.

In 1948, the RDF launched its five-platter plan of weekly radio shows: Five Centuries of French Music presented French orchestral, choir and solo classical performances; Songs of France emphasized folk cultural traditions and their music; Gai Paris Music Hall featured popular music from cabarets and nightclubs curated by the producers of the RDF program Hot Club de France; French in the Air presented language lessons in a humorous vein with a professor, his assistant and a slow-witted pupil; and Bonjour Mesdames (“Hello, Ladies”) explored French fashion and lifestyle topics.

The programs embodied an agreeable and listenable form of cultural diplomacy. Industry journal RPM praised French broadcasting “for bringing the spirit and culture of France without propaganda and without political frills [and] for letting us know that the French people like us and vice versa.” Audiences also embraced programs from Europe on America’s airwaves. “I would like to congratulate you on the fine programs you have been sending to WJWL and assure you that they are being well received by our listeners,” wrote a program director from Delaware. “It is our pleasure to air programs of such high caliber over our station.” At educational station KCVN in Stockton, Calif., Program Manager Marilyn Livingston reported that the five-platter series was “very well accepted and praised highly” by listeners. “We consider the records received from you among the best available,” added the station director at DePauw University’s WGRE. “Many of our listeners tell us that they make a great point of listening particularly to the Masterpieces of France [sic].” WDET in Detroit reported “a large audience” for the FBS series. News of America’s positive reception to the five-platter series provoked one Parisian journalist to wonder half-seriously why France’s broadcasting appeared to reserve its best radio programs for foreigners.

In addition to these platter shows, waves of tape-recorded programs produced for French- and English-speaking audiences also made their way across the Atlantic. WNYC’s Seymour N. Siegel had been experimentally sharing programs recorded on magnetic reel-to-reel tape with members of the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, the forerunner of NPR. The famous “bicycle network” that resulted marked a cooperative, economically sustainable means of supplying desperately needed original content to stations.

In spring 1953, Siegel teamed with Crénesse to enlist the bicycle network to distribute the first of more than 100 taped dramatic, musical, and cultural radio programs produced in Paris. From New York to San Francisco, listeners were treated to the Great Plays Festival, featuring classic French drama by the Comédie Française. They heard performances of classical dramas in French from Molière, Corneille, Hugo and Rostand. Modern works by Giraudoux, Pagnol and Cocteau also circulated. These and hundreds of hours of other French-produced programs would be regularly heard on more than seventy-five NAEB member stations. Even the humblest 250-watt or closed-circuit radio station in Binghamton, N.Y., or New Albany, Ohio, now had access to commercial-free, professionally produced classical and popular music, drama and cultural content from France, along with metropolitan stations in Detroit, Chicago, New York and San Francisco.

As France began to enjoy postwar economic prosperity, it could afford to continue sending high-quality original programs to the resource-scarce independent and public radio listening audience. Though these programs diversified U.S. broadcasting, they also perpetuated ideologies whose gaps and silences influenced U.S.–French cultural politics. The distributions of the 1950s and early 1960s avoided sensitive topics, such as French colonial history, gender and racial discrimination, and ongoing struggles over decolonization. Americans heard programs that emphasized Franco-French cultural achievements while ignoring the peoples and cultures of the former empire and the Francophone world.

The 1974 dissolution of France’s public broadcast monopoly effectively ended the boom years for French radio programs on America’s airwaves. Funding from the Broadcasting Foundation of America, a Rockefeller Foundation project “to nurture an international conversation” between U.S. and foreign broadcasters, helped sustain the transatlantic distribution work somewhat, but the postwar context that drove U.S. and French enthusiasms for exchanges had waned.

Nevertheless, the U.S.–French broadcast partnership of these years supported a crucial stage in the infancy of public radio. French-supplied programs helped diversify the homogeneous programming of U.S. radio. Even if the cultural topics tended to be orthodox and narrowly focused on metropolitan France, they nonetheless brought elements of French culture closer to the U.S. radio audience and stimulated listener interest in France. The platter series brought French culture, music, drama and style to college and university cities and towns and to untold numbers of listeners in metropolitan areas. Supplied free of charge, the programs supported the development of college and nonprofit educational stations, where students, volunteers and paid staff learned to make their own programs, train for careers in the media industries, and experience the creative possibilities of radio. Thanks to the five platters and the programs that followed, the U.S.–French broadcast partnership embodied a transatlantic relationship nurtured by curiosity and a mutual desire to connect via radio.

Derek W. Vaillant is a Professor of Communication and History at the University of Michigan. This article is adapted from the recent book Across the Waves: How the United States and France Shaped the International Age of Radio (University of Illinois Press, 2017).

This essay appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, Current’s series of commentaries about the history of public media. The series is created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the RPTF, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu