Collaboration among Pennsylvania pubmedia documents opioid crisis: ‘The worst is yet to come’

WQED

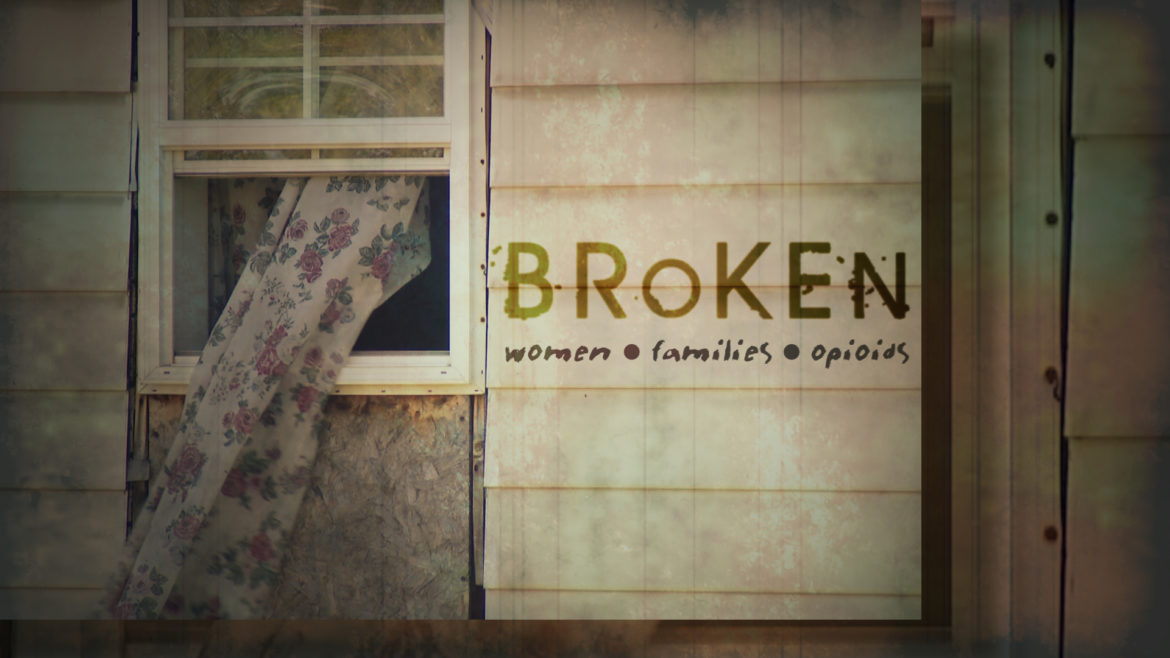

Seven public TV stations in Pennsylvania aired the WQED documentary "Broken: Women • Families • Opioids" March 29.

The opioid crisis has hit Pennsylvania particularly hard. Earlier this year, Governor Tom Wolf issued a disaster declaration for the state’s “heroin and opioid epidemic.” For the state’s media outlets, finding meaningful ways to cover such a big story takes time, resources and talented journalists. That’s why several public television stations realized they could cover the crisis more effectively by joining their efforts. This year, they’re working together to produce the series “Battling Opioids.” It kicked off last month, already bringing in cooperation with state agencies and winning support from the governor. On our podcast The Pub, host Annie Russell interviewed leaders at three of the stations involved. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathleen Pavelko, President, WITF Public Media, Harrisburg, Pa.: The opioid crisis is a national emergency, but here in Pennsylvania we have taken it seriously for quite a few years. First of all, our drug overdose rate is more than twice the national average, and we are reliably informed by officials in state government that the crisis has not yet crested. The worst is yet to come before it gets better.

The other driving force is that disaster declarations in this state and other states are usually reserved for natural calamities. But Gov. Tom Wolf has issued a disaster declaration that we think is the first ever issued for a manmade crisis. So although all of us have been covering this crisis for some years, the fact that the state government has made it a natural-disaster priority also made it important for us to take an even more energetic part.

Tom Currá, CEO, WVIA Public Media, Pittston, Pa.: The latest development is that we met with the Health and Human Services Agency, and we were really looking for the right angle for Pennsylvania public media to get involved. And it boils down to education. They were meeting with the Department of Agriculture as well, and they also are saying that they’re missing the educational piece.

So the Department of Education in our state is now creating a curriculum that’s going to be mandatory, taught in schools throughout the commonwealth next year. And we’re speaking with four agencies in Pennsylvania, talking about developing programs that will not only air on our television stations, but also be used as a resource in the classroom that will connect with the curriculum that the Department of Education is creating.

We will be meeting again, I believe on the 24th of this month, with all four agencies.

Annie Russell, Current: One of the components of this series is a reairing of a documentary about the effect of opioids on women and families in particular. What story did you set out to tell in that documentary?

David Solomon, EP of local production, WQED, Pittsburgh: Our team here produced the documentary Broken: Women – Families – Opioids. We had previously done a documentary a year earlier, Hope After Heroin, which focused on heroin addiction in the Pittsburgh region. During the production phases of that, what kept coming up to our producers was the impact of opioid addiction on women, and why it was different than men.

Obviously it’s devastating across men, women, teens, whomever, but when a woman is addicted to opioids, our research found that it just has a broader reach, and so many more people are impacted by it. Not only are the children of the women affected — either because they are displaced — but they are born addicted, and then when it comes time for a woman to enter recovery or possibly go to jail, what happens to the children? Well, oftentimes they end up in foster homes, or they end up with extended-family members. So it just kind of rolls out in waves when a woman is addicted, and we decided to focus on that angle of the production. That’s why we chose that issue.

Current: Looking forward, can you talk a little bit about the Battling Opioids project and what it’s designed to do?

Currá: It’s designed to inform and educate the public about the crisis. We’re telling a lot of stories about just average people, and how it crosses all demographics and socioeconomic status, and how it impacts society as a whole. Everybody’s talking about the opioid crisis, but what is it? What kind of impact is it having on the communities in Pennsylvania? That’s what we really set out to do. I think it’s important to note that the night that we aired Broken it was common carriage throughout the whole state; we all coordinated to air that film at the same time.

Solomon: Part of the resources that we’re providing it is a lot of the problem stems from the stigma of addiction. People are embarrassed to admit that there’s a family member who’s addicted. They’re embarrassed to admit that they are addicted and that they have children and that they’re addicted. So part of our expertise, obviously, is in producing content and to put more of it out there; that serves as a resource as well to break down the stigma, to get people talking and get them help.

Current: Obviously commercial media is also covering the opioid crisis, and there’s been quite a bit of national attention devoted to this issue. What is public media able to bring to this issue that’s unique?

Currá: It’s not a typical news story. In some cases it may be on the radio, but on television the stories are more developed and more highly produced, as opposed to just putting together a minute-and-a-half piece for the evening news.

Solomon: I also think that we have the ability to tell long-form stories when appropriate and to give the stories the time they deserve. We do a lot of documentary production, and those documentaries not only are in prime time, but they’re also timed in such a way that they can be used as resources in the communities — at community events, in the classroom and other places. And also, even our shorter-form content that could be shared on social media, it’s long enough that it tells the story, makes an impact and provides a resource. A lot of them are informational in nature as well, as opposed to headline-grabbing.

Current: Several stations in Pennsylvania have held town halls on this topic. What did you learn from those forums? And what role will community engagement play in the ongoing coverage?

Solomon: What I learned first was when we did our first town-hall meeting — I believe it was one or two years ago in the fall, and it was on heroin addiction. Sometimes we struggle to fill the studio with people; we have to really put out the call and try to fill the seats on certain topics. What stunned me on this one was a packed house — we had to turn people away. I had not been involved in a town-hall meeting before that was that widely attended by so many people. In fact, it was headquartered in Pittsburgh, at WQED studios, but we had participants in the audience from the center of Pennsylvania — and we’re talking three hours away — that made the trip to attend this town-hall meeting. So the interest is there, and that’s one of the things I learned. The other thing was that they clamored for more, and we had a follow-up related to the Broken documentary on women and opioid addiction — and, again, we had a packed house on that as well.

Pavelko: In the town-hall meetings that we’ve had, and in the comments following programs on social media and so on, I was struck by two different aspects of personal sharing. On the one hand, we heard persons tell their own story of being prescribed opioids for perfectly legitimate reasons but realizing in retrospect that what should have been a prescription for 10 pills was a prescription for 90 pills. There’s now a growing recognition and strong regulatory effort to help physicians prescribe appropriately. But I was struck by people’s personal stories about the overprescribing of opioids.

And the other personal story that I was struck with — both in town meetings and in other comments — was the determination of families who had lost a family member to an overdose, their increasing willingness to say so, including in obituaries and in conversations with family and friends. This gets to the getting past the stigma in order to say, “This has happened. This is a terrible thing. Please be careful for your own family.”

Currá: We were noticing the exact same comments as well. People were becoming more open and actually stating it in their obituaries, death from opioid overdose, and it’s amazing. We’ve just started seeing that over the last month or so.

Solomon: Certainly Tom touched upon this: Education is a key component.

One of the things that we learned in our documentary production and in the town-hall meeting productions was, is the school system ready for this? And when you look at the number of opioid-addicted babies that is on the rise, and the parents who are addicted themselves on the rise, what happens when these children hit third, fourth, fifth and sixth grade a few years from now? Will the school system be ready for it, for behavioral problems that might come along with a learning disability that might come along with it? Oftentimes the parents are the go-to people to help the teachers foster these children through it, and if the parents aren’t capable because there’s an opioid-addiction problem with them, it’s falling squarely in the lap of the schools and the educators.

Current: I think when we see and hear coverage of the opioid crisis, often we’re hearing from folks living with addiction or folks who are in recovery. What effort is there to cover policy and even the pharmaceutical companies themselves as part of this reporting?

Pavelko: WITF’s ongoing series — it’s about 15 years old now — on health-care policy and personal health is called Health Smart, and there are five or six episodes a year. We’ve been addressing the policy questions, that is, what agencies are charged with monitoring prescription traffic? What agencies and regulations are in place to note if an unusual number of pills are coming into some part of the state? What is happening with medical societies and nursing associations to bring those medical professionals up to speed?

Those are the kinds of issues that we’ve been covering on our HealthSmart series, and those will be a continued focus of our coverage because we are seeing increased attention at the state level to the policy implications of this crisis.

Currá: We’re looking at tracking the amount of pills that are going into the communities around the whole state — the counties, the communities — and then aligning those calculations with the population to see what real impact it’s having. And then also the other statistic would be the overdose. We’re tracking it from pharmaceutical companies into communities and then the overdose stats as well. I think that’s really going to give us a picture of what’s happening.

Current: Collaborations between stations in the public media system are pretty common; stations share stories all the time, for example. But what is different about this type of focused coverage that’s done in collaboration?

Pavelko: Collaboration is hard work, especially collaboration that is more than just sharing already-produced pieces. This project involves producing collaboratively as well as sharing programs that have already been produced, and also planning for local productions which fit together into a statewide whole. I have to say that the project manager, Cari Kozicki; David [Solomon], who’s kind of the lead-off producer for one of the programs that we’re sharing; and Tom Currá, the executive producer of the overall project, deserve a lot of credit.

But I will also say that we have staffing groups. We have a group of underwriting and development folks who are meeting; the program directors meet regularly; the production team, the people who produce at the stations related to this project. Each one of those groups is meeting, and the reports out of those groups roll up to the general managers, who meet weekly by conference call.

So if it sounds like a lot of meetings, it’s a lot of meetings. But that’s what collaboration requires.

Solomon: What may also be different about it is that — and I know there is some collaboration on the commercial level — but public broadcasters are kind of seen as the Switzerland of broadcasters. We do come together, and there is no friction in terms of competitiveness. It’s a pretty easy thing when you consider that the bottom line is that we’re trying to do the right thing.

Currá: There really is trust, and we we’re all looking out for each other, and it makes the collaboration process a lot easier.

Current: How will the project be funded going forward? Are stations expected to use their own resources to produce contributions to the series?

Pavelko: The early phase of this is funded by stations’ individual resources, but we believe — based on the experience in other states and what we’re hearing here in the commonwealth — that there should be state regional resources. Some might come from the state itself, and some would come from philanthropic resources and entities interested in improving health care in the commonwealth. So we’re working on all of those.

Currá: The goal is to have really all this work come together in September for Addiction Awareness Month. That was the conversation that we had with the state agencies.

Current: How do you plan to measure the impact of this work?

Pavelko: We’re going to work cooperatively with state agencies to track, for example, the number of referrals that the critical agencies receive, what their website stats are, the number of 1-800 referrals to the state’s hotline, social media reach and impressions. We want to cooperatively track with them to see the trends over time, particularly the impact when our programming efforts are at their height.

Currá: All the general managers in Pennsylvania met with the governor in his office. And he directed us to meet with the four state agencies, and we’ve done that. They must have heard that directly from him as well to receive us.

Pavelko: There is a broad awareness across state government, and in social service and health-care agencies, that this is a crisis that cannot be addressed by a single sector of the commonwealth. It needs to be a multifaceted effort: educational, public policy, health care, regulatory, criminal justice. And I think that’s the way it’s being approached here in Pennsylvania.

We can thanks Obama for this The USA has the highest drug problem ever Eight years of Hell. Our people are dying. (wherethenewsis com)