The survival of public broadcasting’s legacy has long been part of its mission

NPBA

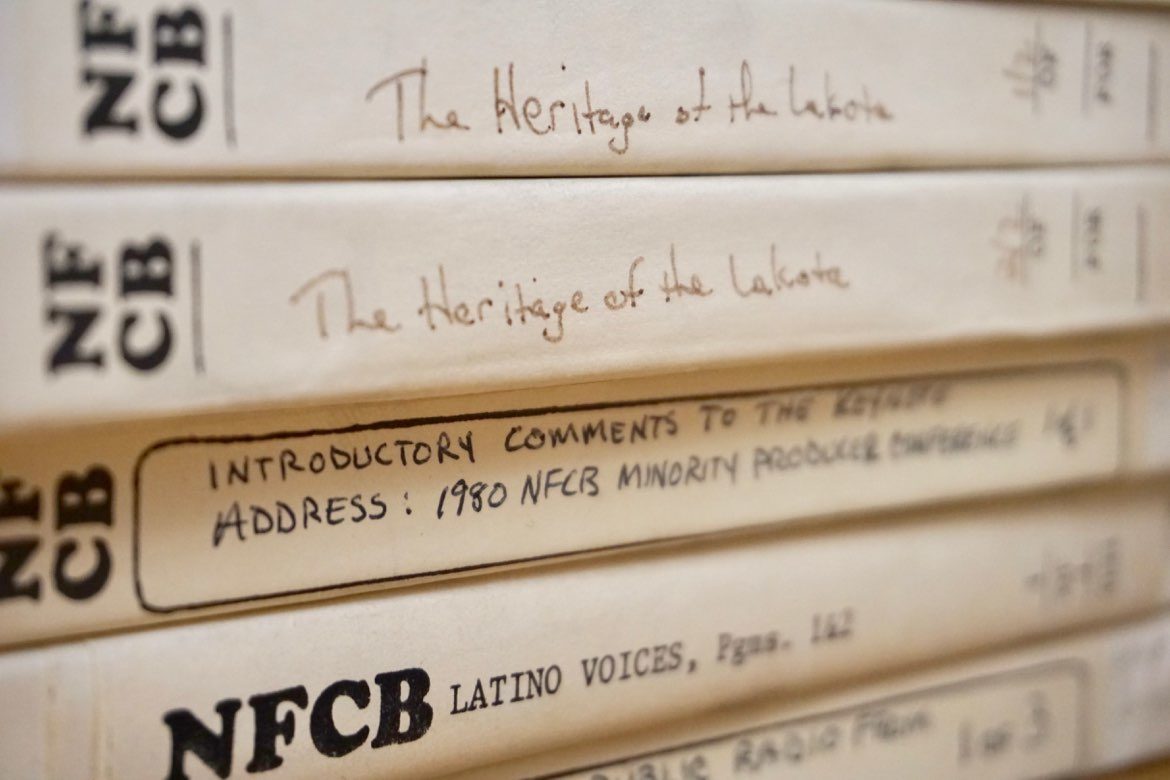

The National Public Broadcasting Archives includes 6,000 reel-to-reel tapes that the National Federation of Community Broadcasters collected in the 1970s and ’80s — one of the only known surviving audio collections that documents underrepresented voices in American media.

Someone is making a documentary about Alfred Butts, the creator of Scrabble. While the game is widely known, the name behind it is not, so I don’t imagine that primary source materials from his life are easy to come by. However, NPR’s Bob Edwards once interviewed Butts on Morning Edition in the 1980s, so when the documentarian contacted me looking for a digital copy, I was glad to provide it. If they want to reuse any portion of it in the film, the producers will need to get permission from NPR; my job as an audiovisual archivist is to help researchers from all backgrounds write their stories of American history.

On a weekly basis, I get all kinds of requests from all kinds of people: a plant pathologist at Kansas State wants a 1984 episode of Frontline, the only known copy of which lives in our stacks; a student from the Berklee College of Music needs a copy of NPR’s program JazzSet from 1994 for a class assignment; a former staff member of a now-defunct community radio station in Seattle would like copies of their programs from our National Federation of Community Broadcasters collection for his online archive; a documentarian from the U.K. who is producing a film on singer-songwriter Don McLean heard about the 1971 interview he did at our student radio station and wants to use it.

As Curator of Mass Media & Culture at the University of Maryland Libraries, I am fortunate to steward what Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden called “the richest audiovisual source of cultural history in the U.S.” She was referring to public broadcasting archives, and she was preaching to a very sympathetic choir comprising academics, archivists and broadcasters at the Radio Preservation Task Force conference in November of 2017. If passion alone could save the history of public broadcasting in the U.S., then this fervent group would have accomplished it upon its formation several years ago. The reality for archivists is that preservation is an ongoing struggle against time and lack of resources to save only a fraction of it. Nevertheless, we persist because we subscribe to the shared belief that keeping pieces of the history of such a vital institution is better than none at all.

As Curator of Mass Media & Culture at the University of Maryland Libraries, I am fortunate to steward what Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden called “the richest audiovisual source of cultural history in the U.S.” She was referring to public broadcasting archives, and she was preaching to a very sympathetic choir comprising academics, archivists and broadcasters at the Radio Preservation Task Force conference in November of 2017. If passion alone could save the history of public broadcasting in the U.S., then this fervent group would have accomplished it upon its formation several years ago. The reality for archivists is that preservation is an ongoing struggle against time and lack of resources to save only a fraction of it. Nevertheless, we persist because we subscribe to the shared belief that keeping pieces of the history of such a vital institution is better than none at all.

Since the Public Broadcasting Act was passed by Congress in 1967, the core mission of both public radio and television broadcasters has been to serve an educated, informed and engaged audience. Much of the programming was meant to fill the void left by commercial broadcasters who, in deference to their sponsors, focus on the broadest possible appeal. This isn’t to say that commercial networks haven’t created innovative and important programs along the way, but in their mission to entertain and sell, they skew towards the white, middle-class, male demographic generally favored in popular culture. For noncommercial broadcasters, radio and television have been spaces for the public exchange of ideas from people of diverse backgrounds and experiences, resulting in programs that not only have more inclusive narratives and perspectives but that encompass a much fuller representation of the American cultural experience.

At the University of Maryland, the National Public Broadcasting Archives has been a signature of Special Collections for 28 years. It was initiated by educator and former PBS board member Donald McNeil, who solicited archival materials from broadcasting organizations and educational institutions, including CPB, PBS, NPR and the Academy for Educational Development. McNeil found a repository at UMD, and the NPBA was officially dedicated June 1, 1990. Since then, the collection has grown to include organizational records, program archives and personal papers of hundreds of public broadcasting–related entities and individuals throughout the U.S.

For me, the most important and challenging components of the NPBA are the program archives. These are the creative embodiments of stations’ missions and the most unique cultural artifacts in any broadcast collection. But since no one has ever invented a stable medium for audiovisual content, managing the array of legacy formats in our holdings means a constant race against time. Whereas paper-based archives, when kept in the right conditions, can remain legible for centuries, even decades-old AV media is already at risk. It often surprises people to hear that compact discs, favored by both consumers and professionals in the 1990s, have already shown a remarkably high rate of data loss. Analog videotape from the 1970s and ’80s isn’t faring well, either. One of my colleagues recently had our vendor digitize an important collection of VHS tapes and found that half of them had severe audio distortion or loss. And it gets expensive: The cost of transferring, say, 500 ¼” magnetic audio reels is about $15,000, more if the tapes require conservation work. The scarcity and cost of maintaining legacy equipment, which can run into tens of thousands of dollars as well, also prevents many institutions from reformatting their AV holdings themselves. Unfortunately, without a working 1” Type C machine, a 1” Type C videotape is essentially useless.

This can be discouraging. Some days, or even weeks, it feels like a losing battle. But in my fourteen years as an AV archivist, I’ve learned that the preservation potential of any collection lies in its uniqueness and historical value, the timeliness of milestone achievements, and partnerships based on mutual dedication. And of the hundreds of collections in our holdings, these qualities most often show up in the NPBA.

In the aforementioned NFCB collection, for example, there are over 6,000 reel-to-reel tapes that the organization collected during their Program Exchange in the 1970s and ’80s. This is one of the only known surviving audio collections that documents underrepresented voices in American media. Spoken-word programs include documentaries on cultural issues of marginalized communities, such as Song of the Indian: Indian Verses, Whiteman’s Values (KBSB), How To Get Birth Control (KBDY) and Who Are the Panthers? (KBOO). Many of the tapes also contain live performances from all over the world, particularly in cultures where music has not been traditionally preserved via sound recordings, such as Brazilian Capoeira, Peruvian Indians Q’ero Tribe and Songs, Chants and Hakas of the Maori. Last year, we received a Recordings-at-Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources that will enable us to digitize 600 of these tapes, and we are currently developing online teaching and learning resources to promote their use in classrooms and scholarship.

The upcoming 50th anniversary of Maryland Public Television in 2019 has given us the opportunity to use one of our most important regional television collections as a platform for outreach. Two years ago, we started working with MPT to digitize their program history. They have helped us identify a representative sample of their best shows from among the thousands of videotapes in our holdings. Episodes of Our Beautiful Planet, Inside Maryland, Chesapeake Cooking, Lifelines, Economic Perspectives and State of the State will soon be accessible via UMD’s Digital Collections online, as well as in the digital archives of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting. A selection of these programs will be featured in the gallery exhibit we’re planning for the 2019/2020 academic year that will both showcase their importance as Maryland’s only statewide public television broadcaster and launch a fundraising campaign for ongoing preservation of their archives.

For patrons, our most accessible AV collection is the National Public Radio archive, due to the fact that NPR has done such an outstanding job saving their own history. No other broadcast entity that I’ve worked with, commercial or noncommercial, has maintained such a comprehensive preservation program. In another piece written for this series, Ayda Pourasad and Julie Rogers of NPR describe the meticulous cataloging and digitization projects that have ensured the survival of their legacy. The enormous breadth of issues, events, ideas and people that NPR has featured in their 47 years on the air means that researchers from all disciplines can mine it for primary source material. Just last week, a visual-arts curator from Ohio working on a retrospective exhibit of the American painter Robert H. Colescott emailed me asking for a copy of the artist’s interview on All Things Considered in 1989. NPR transferred that program from its original master reel years ago and more recently migrated the access copy from CD to their internal database. It took about five minutes for me to download it and send it to the patron.

What I’ve discovered in working with public broadcasters is that dedication to programming that serves the common good hasn’t been their only focus. A large number of them, far more than any commercial organization, have made painstaking efforts to archive their histories. (More recently, the national preservation initiative of WGBH’s American Archive of Public Broadcasting and the impressive program launched by Rocky Mountain Public Media have synthesized crowdsourcing and emerging technologies.) While many are not trained archivists, they know what they have created is important and valuable, and so they store their master tapes and organizational records where and when they can, rightfully believing that one day they will be useful to someone. Thanks to them, gems of public broadcasting’s legacy remain an accessible part of our cultural history.

Laura Schnitker is an audiovisual archivist and curator of Mass Media & Culture in Special Collections at the University of Maryland Libraries. She is also a lecturer in the School of Music and hosts a weekly radio show on WMUC-FM.

This essay appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, Current’s series of commentaries about the history of public media. The series is created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the RPTF, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu